Preface

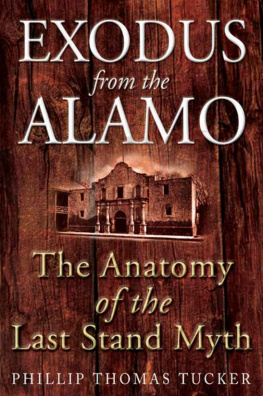

Almost everything Americans have been taught, or think they know, about the Alamo is not only wrong, it is nearly the antithesis of what really occurred on the early morning of March 6, 1836. The battle that was fought has been embellished over many decades through story, song, and cinema, resulting in a mythical Alamo and an enduring romantic legend based upon a simplistic morality of play of good versus evil. This myth is founded on the notion of a heroic last stand, which allegedly resulted in the deaths of hundreds of attackers as every defender of the garrison fought at his post, dying to the last man in a deliberate act of self-sacrifice. New documents, especially Mexican and Tejano, and careful historical research definitively prove that the real truth is far more complex, and that this traditional heart of the Alamo story is largely false, based on fantasy rather than historical fact.

The cornerstone of the Alamo myth has been so powerful that it has never been seriously investigated. Moreover, no historian has ever asked a relatively simple, elementary question: If all of the defenders were killed, then how do we really know what happened at the Alamo? Even more importantly, was there actually a heroic last stand? And how can we know what in fact happened, since the fighting inside the Alamo took place in predawn darkness? This unusual twin handicapthe lack of garrison survivors and a struggle that occurred in blacknesshas made it unusually difficult to ascertain tactical developments and the course of the fighting, leaving historians and writers guessing at the details.

A fresh, unbiased perspective on the Alamo is especially long overdue, given that current stereotypes and myths about the battle were created by writers and journalists long before professional historians explored the subject. Serious investigation requires us to cut through multiple layers of romantic fantasy and literally start from scratch. Almost everything that we know about the Alamo has been based on third-hand, inaccurate, and biased accounts from highly questionable sources; moreover, these tell the story from primarily one sidethe side that possessed a vested interest in laying the foundation for the mythical last stand. Most importantly, it is necessary to understand and reconstruct the struggle realistically, in its setting of predawn darkness, yet previous books on the subject have portrayed the contest as a setpiece battle fought in broad daylight.

Nor was the Alamo an epic clash of strategic importance, as it is so commonly portrayed. One undeniable truth about the events came directly from Mexicos top military commander. The commander-inchief of the Army of Operations, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, baldly, almost nonchalantly, described the struggle to possess the Alamo as but a small affair. American historians have nevertheless ignored such views because they contradict the romantic lore surrounding the Alamo, and especially call into question the fabled last stand.

One of the great iconic, though widely misunderstood, stories of American history, the Alamo has been distinguished by a seemingly endless number of enduring mysteries. Few concrete facts, including even the exact number of Alamo defenders, can be verified with a degree of certainty. The Alamo myth is firmly entrenched as a piece of national folklore, while ironically, the true story of what actually occurred lies hidden in newly found or previously overlooked accounts by forgotten Mexican soldiers and officers. Other better known accounts by Santa Annas men, including those that magnified the resistance and the defenders heroism to reflect favorably upon themselves and to portray events as a battle rather than a massacre, have proven less reliable.

In truth, the Alamo was a surprisingly brief clash of arms. Only later did admiring generations of Americans invent the myth of a great heroic battle in order to obscure a host of ugly, embarrassing realities. These included the fact that consecutive commanders of the Alamo needlessly lost the tiny garrison instead of withdrawing earlier to fight another day. The ensuing disaster was reinvented as a noble self-sacrifice in the cause to save Texas, ignoring the obvious fact that those leaders foolishly chose to fight and die at a place of no strategic importance and for no gain.

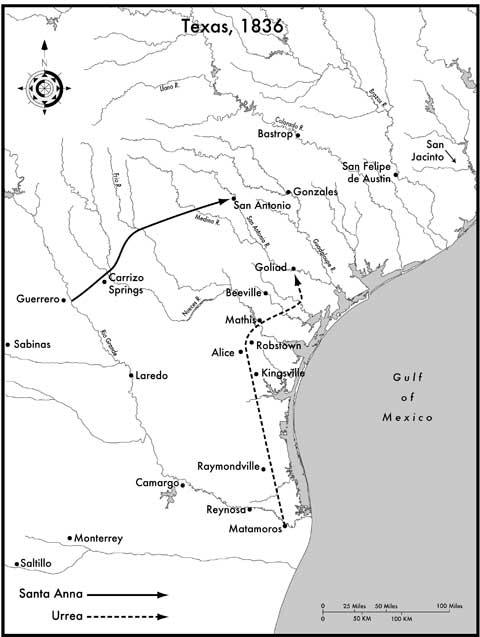

Rather than mounting a climactic last stand with a well-organized, tenacious defense, a totally unprepared Alamo garrison was caught in its sleep by a well-conceived night attack that took the men completely by surprise. The garrison consisted of citizen-soldiers with little of the military training or experience of their well-honed Mexican opponents, whose attack left them so stunned that they never recovered from the shock. This initial tactical success ensured that hundreds of veteran Mexican troops had already reached the Alamos walls before garrison members were aroused from their sleeping quarters, negating any chance of an organized, effective, or sustained defense.

More of a rout and a slaughter than a battle in the traditional sense, the struggle for the Alamo lasted only about twenty minutes, making it one of the shortest armed clashes in American military history for an iconic battle. Winning one of his easiest victories, Santa Annas success was ensured when his troops swiftly breached the walls. This tactical success directly contradicts the portrayal of the event as an epic conventional battle, as envisioned by generations of historians and writers, Hollywood filmmakers, painters and artists. Common depictions show the entire garrison aligned in their assigned defensive positions along the walls, manning their blazing artillery, offering organized resistance, and inflicting terrible damage on the attackers under daylight conditions. However, new evidence from the most reliable sources shows that even the heroic last stand immediately in front of the Alamo church and its famous facade is a romantic embellishment. Instead, a large percentageperhaps the majorityof the garrison fled in multiple attempts to escape the slaughter, trying to quit the compound before the battle inside had ended. No unified, solid defense took place along the walls that dark, early morning. In fact, the defense of the perimeter was so relatively weak that some of the hardest fighting very likely occurred outside the garrison walls, resulting in the deaths of more defenders outside than inside the Alamo.