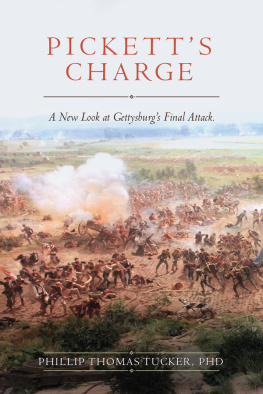

Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2013 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

908 Darby Road, Havertown, PA 19083

and

10 Hythe Bridge Street, Oxford, OX1 2EW

Copyright 2013 Phillip Thomas Tucker

ISBN 978-1-61200-179-1

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-61200-180-7

The maps in this book are courtesy of Bradley M. Gottfried from his work

The Maps of Gettysburg, Savas-Beatie Publishers, 2007.

Cataloging-in-publication data is available from the Library of Congress

and the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without

permission from the Publisher in writing.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

For a complete list of Casemate titles please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131, Fax (610) 853-9146

E-mail: casemate@casematepublishing.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249, Fax (01865) 794449

E-mail:

Contents

Introduction

A CCORDING TO CONVENTIONAL wisdom, Picketts Charge has been long seen as the climax of Gettysburg, the largest and most important battle fought on American soil. But contrary to traditional assumptions, the failure of Picketts Charge, despite all its tragic majesty and heroic grandeur, was not the decisive event that condemned the Army of Northern Virginia and the Confederacy to an early death. In truth, Gettysburg was decided not on the famous third day of the battle, but on the previous afternoon. Indeed, Thursday, July 2, 1863 was the most important day in the Confederacys short lifetime and the most decisive of the three days at Gettysburg. And the defining moment of that Second Day was the repulse of the most successful Confederate attack, which came closer to toppling the Army of the Potomac than any other Rebel offensive effort of the war. It was the charge of General William Barksdale and his 1,600-man Mississippi Brigade on the afternoon of July 2, which one Union observer described as the grandest charge that was ever made by mortal man.

Unfortunately, the mythical qualities and romantic dimensions of the most famous assault in American history, Picketts Charge, has left a far more successful Southern attackone that swept through and routed much of a veteran Union Corps, captured nearly 20 artillery pieces, and penetrated more than a mile to drive a deep wedge into the Union armys left-centerin the historical shadows, and often only in obscure footnotes of books about the Battle of Gettysburg. In truth, however, Barksdales attackas the foremost spearhead of Longstreets offensive on July 2came closer to achieving decisive success and winning it all for the Confederacy than any other assault of the battle.

In Americas fabled national Iliad, the relatively slight, ever-so-brief penetration of the Union center by the courageous attackers of GeneralGeorge Edward Picketts Virginia Division on July 3 has been long celebrated as the High Water Mark of Gettysburg and the Confederacy. But only a relatively few men of a depleted band of attackers ever reached the little copse of trees on the Union right-center along Cemetery Ridge, and once there could only fall to Union fire or be captured. In terms of achieving the greatest gains and coming closer to achieving decisive success, the High Water Mark of Gettysburg has long been located in the wrong place.

After the war, United States government historian John Bachelder officially establishedor rather inventedthe High Water Mark at the copse of trees along Cemetery Ridge. Influenced by powerful veteran groups from both sides, especially Picketts Virginians, Bachelders designation became the established High Water Mark that has forever commemorated the geographical and military zenith of Confederate fortunes during the four years of war. Therefore, Picketts Charge has been widely seen as Lees best chance to have won the battle, which was not the case. Propelled by the tide of popular history based upon the much embellished Virginia version of the story, generations of historians and popular writers have long celebrated the Rebel zenith on the incorrect day and place.

The true High Water Mark of the Battle of Gettysburg took place farther south of the famous clump of trees, near Cemetery Ridges southern end on the Union left-center, where Barksdale struck with his brigade. In terms of its overall success, gains reaped, and closeness to achieving a decisive victory, Picketts Charge was neither the most successful nor most important Confederate attack at Gettysburg. In fact, it never came close to achieving what had been accomplished and gained by the Mississippi Brigades sweeping attack the day before.

Unlike when Barksdales men smashed through the Union left-center, at a time when it was most vulnerable, General Robert E. Lees decision to target the Federal right-center on July 3 was made when it was far too strongin terms of the number of defenders, both front-line and reserve, excellent elevated defensive terrain, and high-quality Union commandersto overcome. Quite unlike Barksdales Charge on July 2 when the fate of the American nation was decided, Picketts Charge never really had a chance of succeeding.

Seldom before and afterward would Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia come closer to achieving decisive victory than when Barksdales Charge came so tantalizing close to cracking the Union line on the late afternoon of July 2. Under Barksdales inspired leadership, the Mississippi Brigades success in smashing everything in its path, including the Peach Orchard salient and the Emmitsburg Road defensive line, was remarkable by any measure. A single regiment of Barksdales Brigade (the 21st Mississippi) captured more artillery pieces than any regiment on either side at Gettysburg. As never before, Barksdale went for broke in personally leading his brigades onslaught in an attempt to win the war in a single afternoon. And he nearly succeeded.

But in one of the great inequities of American history, Barksdales Charge has long remained in the shadow of Picketts Charge, thanks largely to the dominance of the Virginia School of history. The general obscurity of Barksdales effort, despite its tactical success, has resulted from the sheer power of myth, traditionalism, and romance in both popular and academic history. As fate would have it, the Mississippians attack was never promoted, embellished, or celebrated by generations of historians after the Civil War. Southern writers favored the gallant effort of the Virginians, while Northern writers preferred to celebrate their clear triumph over Picketts men rather than the moment when their line was barely hanging by a thread, and elements of four corps were forced to converge to stop the onslaught of Barksdales Mississippians.

Pro-Virginia propagandists early rewrote the dramatic story of Gettysburgs Third Day to conform to a chivalric and heroic tale dominated by layers of Victorian Era values and romance. They succeeded in transforming the folly of Picketts Charge into the most romanticized saga of the Civil War. The aggressive advocates and prolific writers of the Virginia School, which glorified Virginian leaders, troops, and accomplishments, decisively influenced generations of latter-day historians, popular writers (ironically including Mississippis own William Faulkner), documentaries, and films for generations to come. Unlike Pickett, whose enduring romantic image was largely the product of the writings of his well-connected Virginia wife, the Deep South general, William Barksdale, who led the far more successful charge at Gettysburg, was forgotten.

Next page