Campaign 52

Gettysburg 1863

High tide of the Confederacy

Carl Smith Illustrated by Adam Hook

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

G ettysburg just seemed to happen. No great plan declared that Meade would stop Lees army at this spot. The armies, which had been moving on parallel courses, just seemed to blunder into each other and skirmish, and then their respective commanders decided that here was as good a place as anywhere to fight a battle.

Gettysburg was the turning point of the American Civil War: afterwards Confederate hopes of establishing a separate nation dwindled as the likelihood of winning or of enticing European intervention waned. The South did not feel Gettysburg was a pivotal encounter, and Northern voices severely criticized Meade for allowing the Army of Northern Virginia to escape intact. That Gettysburg should occur was inevitable, but that it occurred the way it did and where it did was the result of a series of coincidences.

Gettysburg was a city of little military importance. Most of the surrounding area was farmland and orchards, long shorn of old forest growth, and the basically flat lands were broken only by low ridges and gentle hills. Boasting a rail line to the east and an unimproved cut where the track would be laid to the west, the town had a Lutheran seminary on a nearby hill and was the nexus of roads leading to Washington, Philadelphia, or Harrisburg. The steeple of the Lutheran church was the highest man-made site. The rumour of a warehouse filled with shoes may have been started by Heth to justify his contravening Lees orders not to initiate a general engagement without orders. Until 30 June, there was nothing in the area to interest the Union Army except the Army of Northern Virginia, which had slipped away from Hooker in Virginia and had moved north.

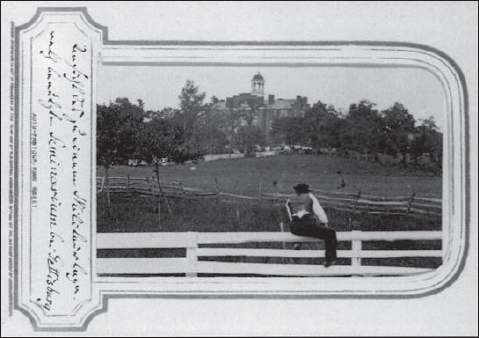

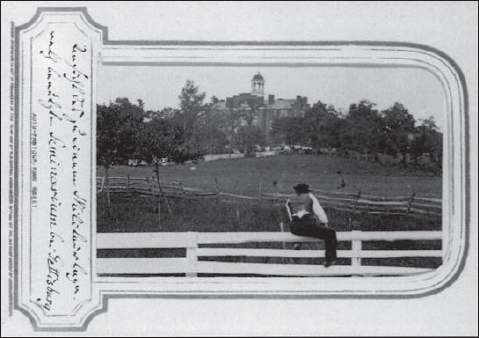

Postcard view of Gettysburgs Lutheran Seminarys east side, showing the cupola where Buford watched the Confederate advance. This part reached above the canopy of trees and afforded a clear view of Herr and McPherson Ridges.

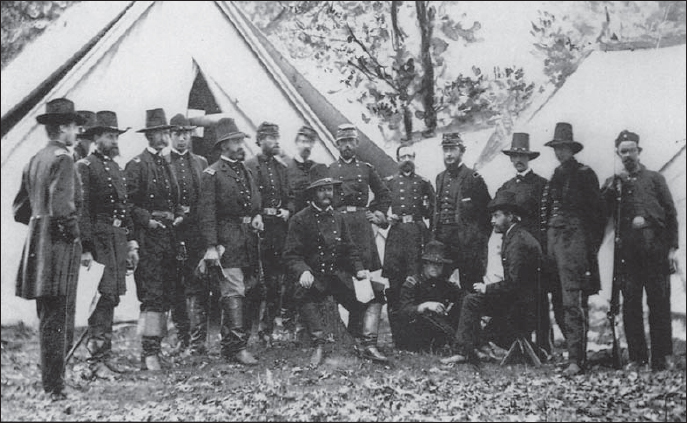

Burnside and his staff before Hooker relieved him of command of the Army of the Potomac. Hookers days were numbered because of his reluctance to engage Lee.

After Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville the Army of the Potomac was demoralized. Their overly cautious fourth commander, Gen. Joseph (Fightin Joe) Hooker, was wary of being too aggressive after Jackson and Lees triumph at Chancellorsville, lest Lee leave his fortifications at Fredericksburg, defeat Hooker and then march on to Washington, D.C. with no Union Army to impede him. The spectre of a Confederate advance east burdened every Army of the Potomac commander, but none more so than Hooker.

Events at Gettysburg were set in motion before Fredericksburg. After Antietam, Lees 1862 northern campaign halted. Yet Lees desire to invade the Union remained strong, as did his belief that if he could just take the war north, Yankee pro-war sentiments would wane.

Lee had to take the war north. Another summer campaign would be disastrous for Virginia farmers because they could neither plant nor harvest crops. Furthermore, a timely Confederate thrust might relieve pressure on Vicksburg in the west, since Northerners, feeling endangered, might demand placement of military garrisons in their key cities, which would involve withdrawing troops from the west as well as from the east. Finally, if England and France saw an aggressive and victorious Southern Army, either might enter the war on behalf of the beleaguered Confederacy, or at least give the Union good reason to sue for peace with Richmond on its own terms before they took an active interest in the war.

Next to Lee, Jackson had been the most aggressive commander of the South. Jacksons death had removed one half of Lees corps commanders and Lee had had to restaff his command. (Longstreet was good, but cautious.) Time was a constraint: the war had to go north that year, before summer too, otherwise winter would catch the Confederates trying to live off hostile land. Lee well understood the horrors of Napoleons Moscow campaign, and that his own invasion called for stealth. By quietly moving his army piecemeal, new corps commanders would have time to become acquainted with their responsibilities, with Lees command style and with the enemy commanders facing them. By the time they engaged in combat, they would be comfortable with the command structure. Although his corps commanders were new, they were competent generals, and Lee had the greatest confidence in his troops.

Maine infantry in 1863 wearing shorter uniform blouses instead of the earlier issue frock coat; the officer wears a shell jacket. Note the variations between officer, drummer, and enlisted field dress. Wearing leggings seemed a matter of individual preference rather than regulation.

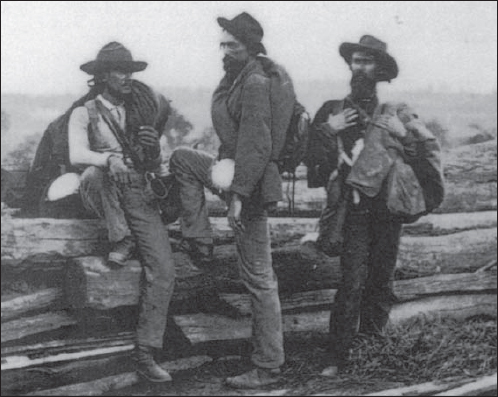

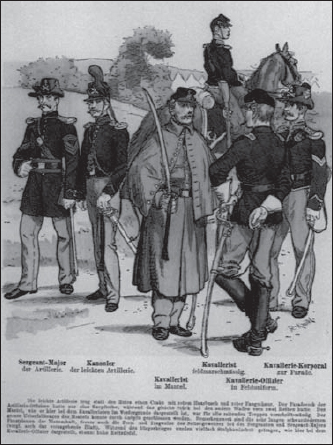

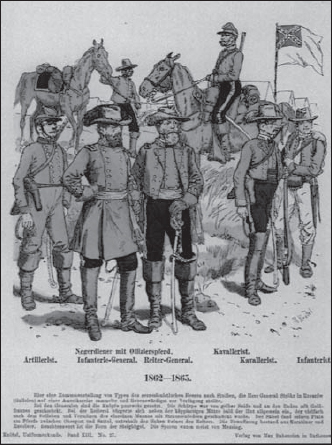

European idealized representations of Confederate and Federal Army uniforms. Although these were the official uniforms, men in the field wasted little time modifying them for battlefield conditions. Many soldiers started out with these uniforms, but by 1863 battlefield dress was for comfort and flexibility; superfluous items had been discarded long ago. Shortage of material, uncertain supply, and field conditions dictated personal uniform modification.

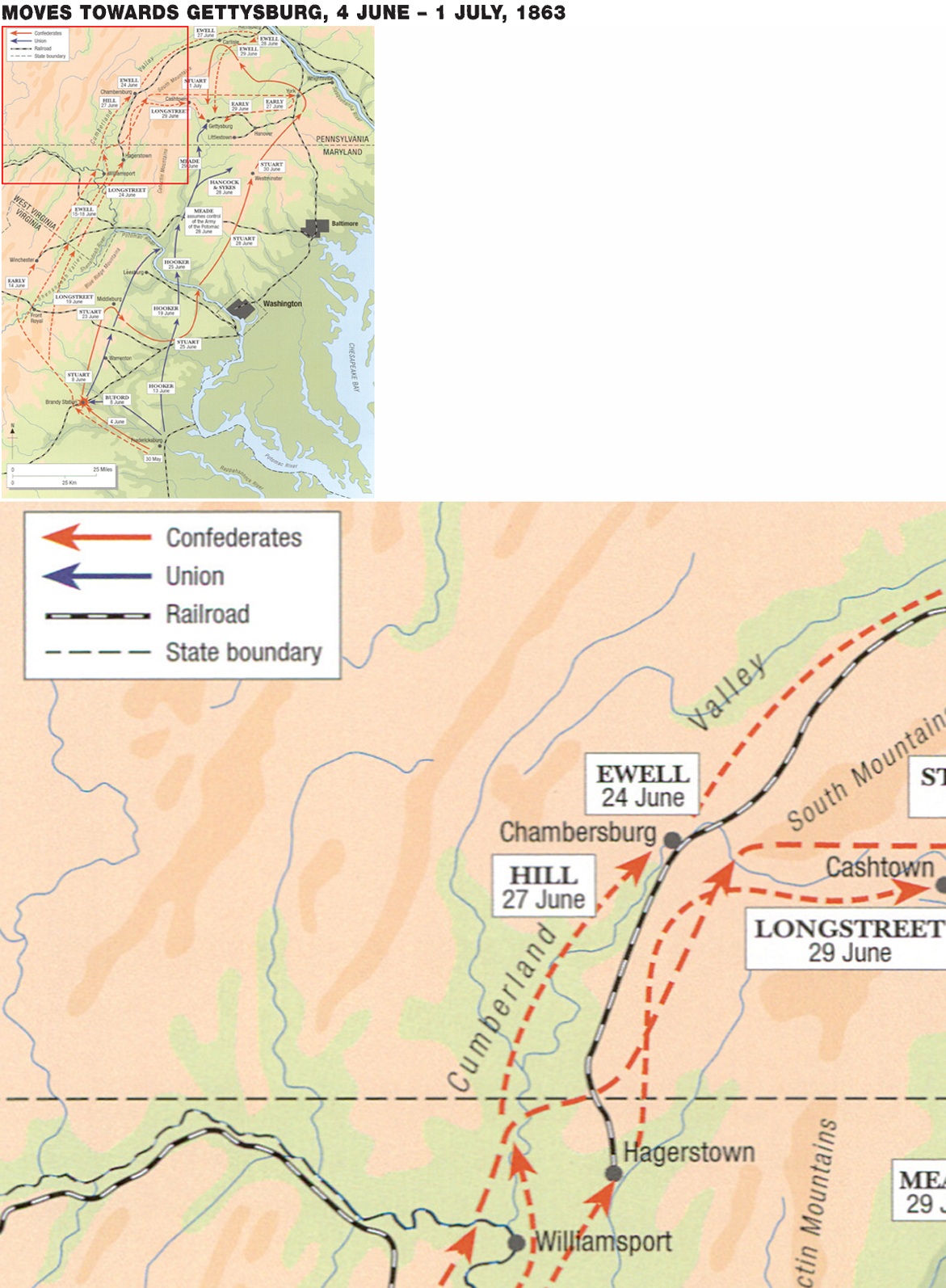

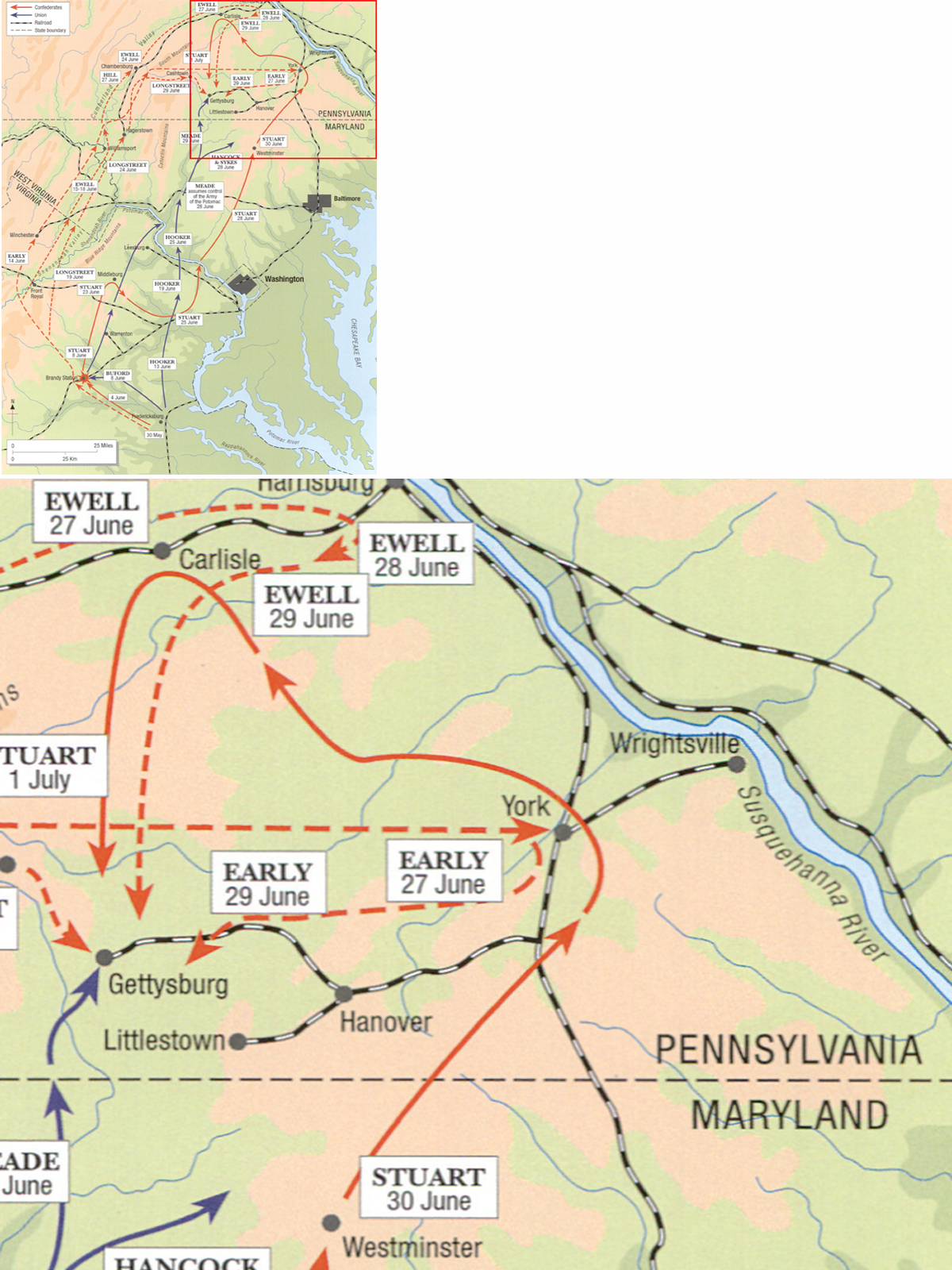

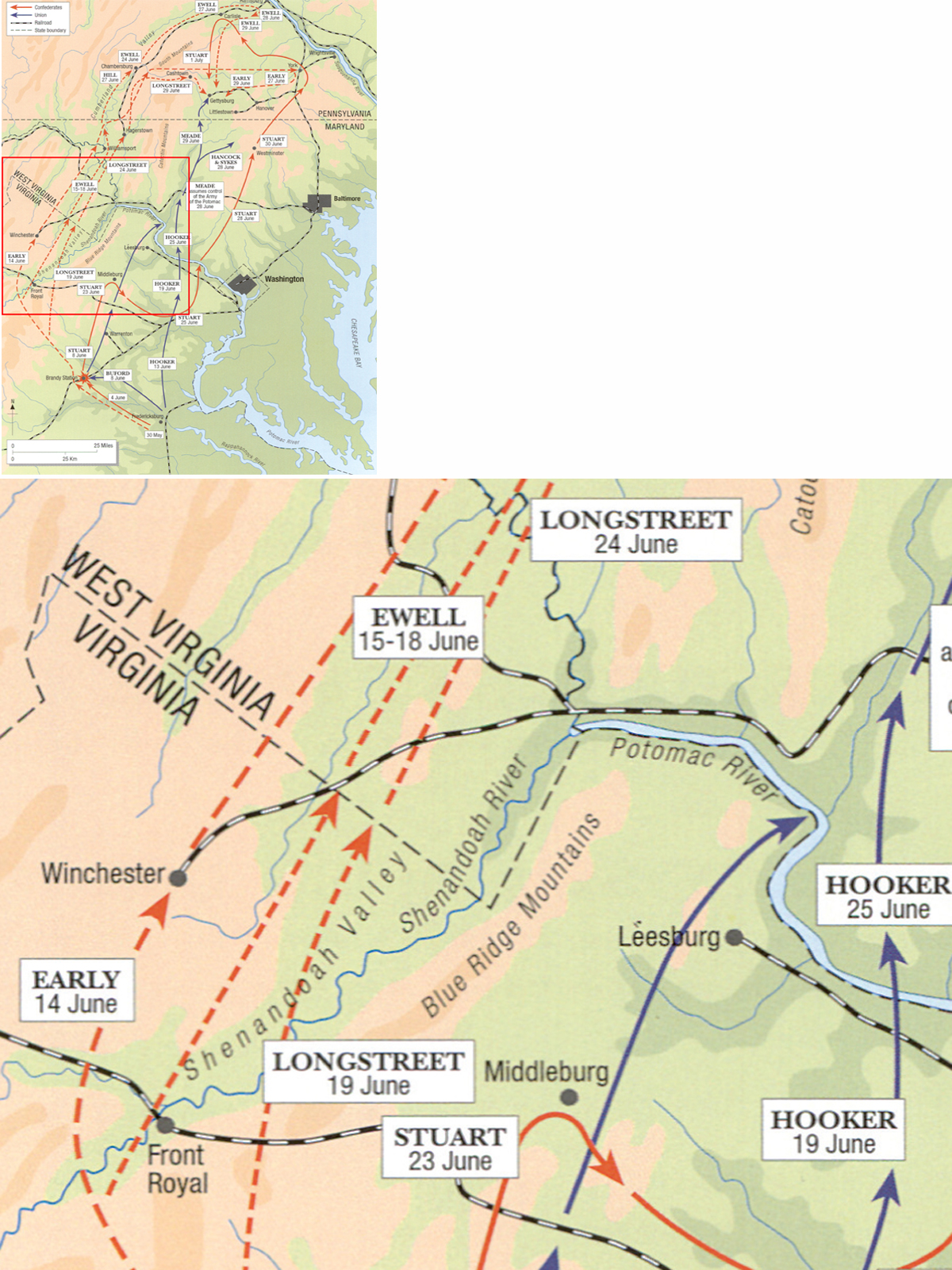

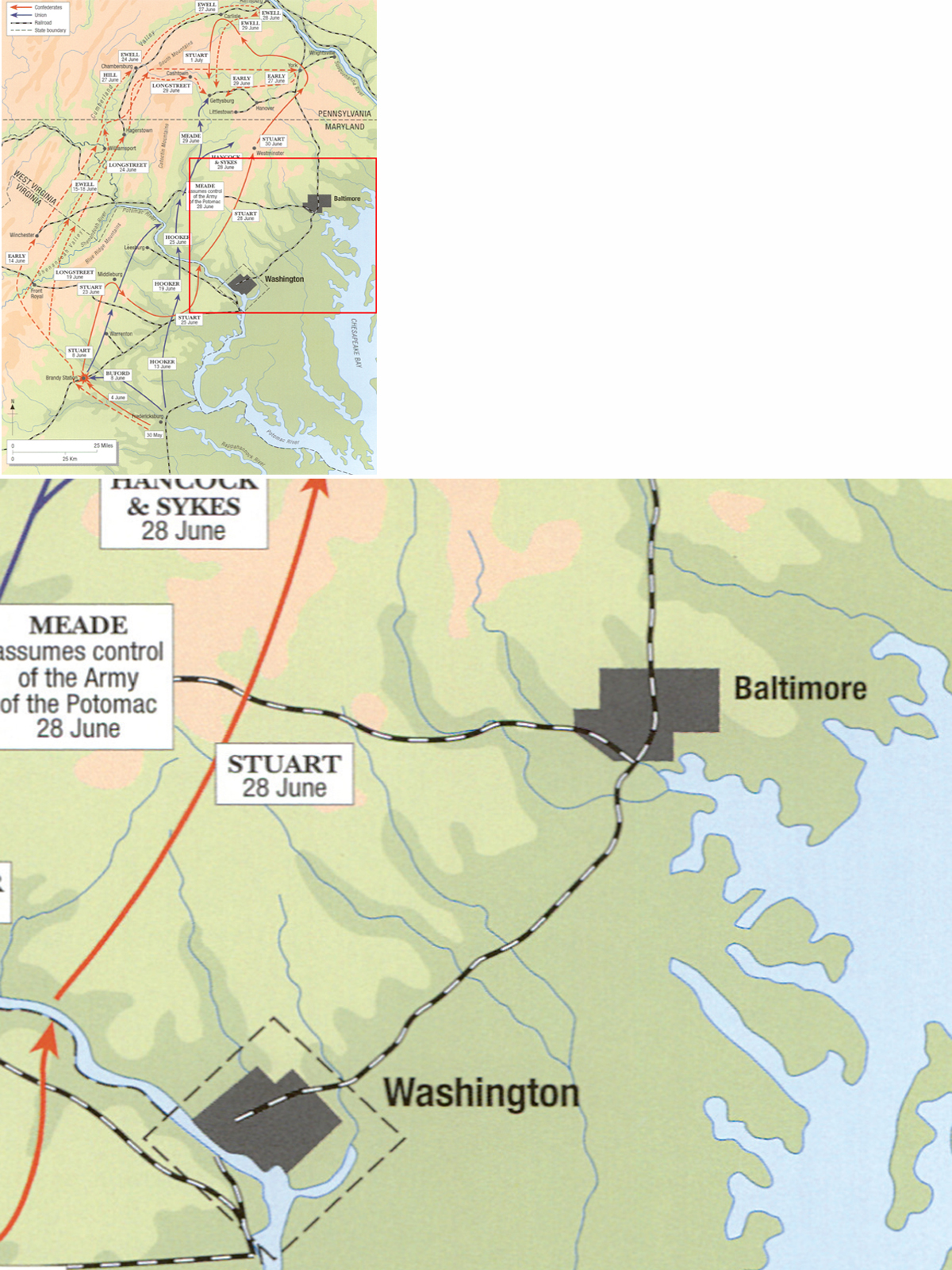

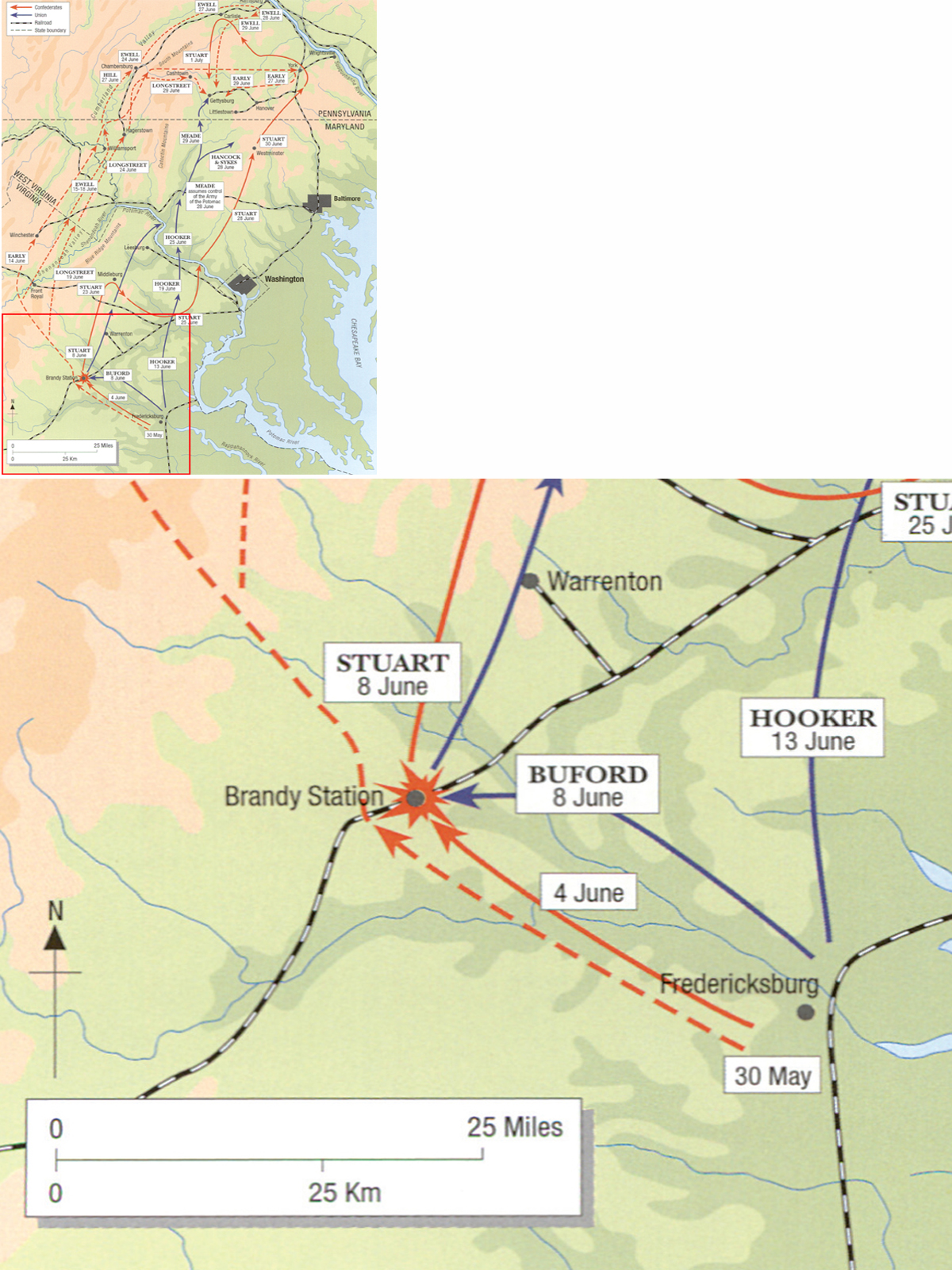

Lees plan was to steal a march on the Army of the Potomac. Once distanced from Federal troops, the Army of Northern Virginia would effectively disappear as Stuarts cavalry screened its movements from Union forces. The Army of Northern Virginia could then strike at Pennsylvania or possibly as far as Harrisburg before swinging down to Maryland, while Stuarts cavalry protected their route of march and denied Hooker intelligence of their actions until it was too late. The Union Army would have to leave Virginia to chase and engage Lee in a battle at a time and place of Lees choosing. In so doing he would defeat the Federal Army. He had considered all these factors before Chancellorsville.