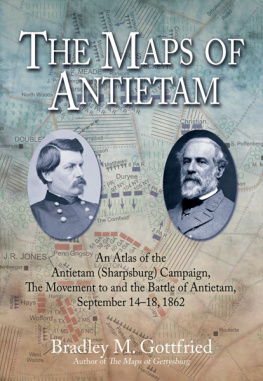

2007 by Bradley M. Gottfried

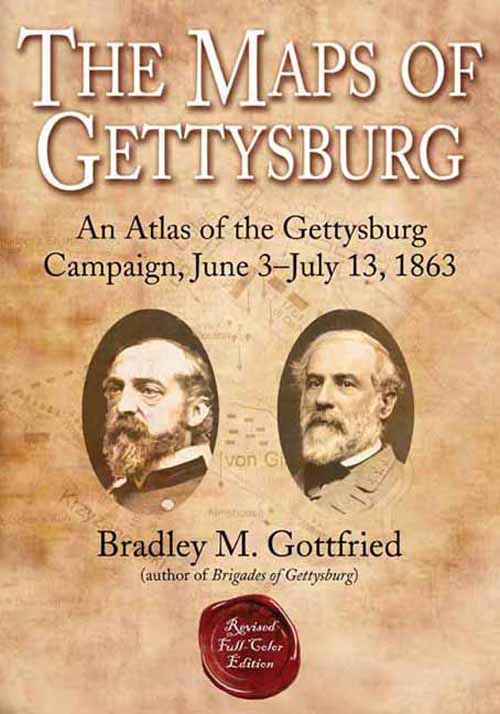

The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 July 13, 1863

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

Original edition published in black and white in 2007

ISBN-13: 978-1-932714-82-1

eISBN: 9781611210255

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition, First Printing, Color edition, 2010

Published by

Savas Beatie LLC

521 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1700

New York, NY 10175

Editorial Offices:

Savas Beatie LLC

P.O. Box 4527

El Dorado Hills, CA 95762

Phone: 916-941-6896

(E-mail) editorial@savasbeatie.com

Savas Beatie titles are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more details, please contact Special Sales, P.O. Box 4527, El Dorado Hills, CA 95762. You may also e-mail us at sales@savasbeatie.com, or click over for a visit to our website at www.savasbeatie.com for additional information.

For Linda Nieman and Theodore P. Savas,

whose support and interest made this book possible.

List of Maps

Introduction

Another book on Gettysburg?

A few years ago, a distinguished Civil War historian decried the continual flow of books, articles, and research on the battle of Gettysburg. As far as he was concerned, the energy poured into the battle directed attention away from other important events that needed scholarly attention. One of the books he focused attention on in his article was my own recently released Brigades of Gettysburg: The Union and Confederate Brigades at the Battle of Gettysburg (Da Capo, 2002). That title, and others like it, intoned the historian, was what was wrong with modern Civil War historiography. Although I respect his broad body of work, and own many of his books, I disagree entirely with his assessment.

First, no other campaign has uncovered so many first-person accounts of those pivotal weeks in 1863. These recollections make it easier for anyone writing on the subject to understandat a much broader and deeper levelwhat really occurred during that campaign. This is true not only at the strategic level, but from the eyes of men who served in the ranks and from the perspective of ordinary civilians. Newly discovered accounts on this subject appear with regularity. As ongoing research turns up new sources, it is the historians job to synthesize that material and produce something useful from it. The recently published and well received Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuarts Controversial Ride to Gettysburg, by Eric J. Wittenberg and J. David Petruzzi (Savas Beatie, 2006) is a classic example of what good historians can do with new material.

Second, the national interest in Gettysburg continues unabated. Attendance at the national park dedicated to memorializing the battle has fallen recently, but nearly 2,000,000 people still visit each year. Books on the subject continue to sell well because the interest in reading about the campaign remains vibrant.

All of this is a roundabout way of coming back to how this Introduction opened. In your hands is another book with Gettysburg in the title (twice). My own work on the subject is concentrated on topics I think others want to read more about, including reference material that will hopefully assist experts and laymen alike. I am a firm believer that plowing ground that will help others in the future is a worthwhile endeavor.

Researching and preparing Brigades of Gettysburg in the late 1990s was much more difficult than I expected it might be. A dearth of easy-to-read complete maps on the campaign made tracking the daily movement of the opposing armies and individual units much more difficult than it would otherwise have been. To understand fully any campaign or battle, a student must appreciate how and when the individual armies and their component parts marched to the battlefield and their proximity to one another along the way at any given time. Being able to visualize this information makes it come alive and weaves the threads of understanding together into a tighter picture that usually explains why commanders marched when and where they did, or why they made one decision and not another. Knowing the precise movements of the opposing forces also sheds light on why and when a particular battle took place. Understanding how the opposing armies reached the field of battle goes a long way toward explaining why the subsequent fighting unfolded as it did. This is true of every military campaign of every age.

When it comes to Gettysburg, readers have several cartographic works from which to choose. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Any serious study of Gettysburg must include time with John Bachelders maps. These maps are invaluable for studying the battle. However, Bachelders maps only cover the events on the field at Gettysburg, and although crafted with care, contain many inaccuracies. John Imhofs GettysburgDay Two: A Study in Maps (Butternut and Blue, 1997) is an outstanding work designed to cover only a slice of the battle (the second day); it does so admirably. Another similar study includes Jeffrey Halls The Stand of the U.S. Army at Gettysburg (Indiana University Press, 2003). The topographical maps are impressive and helpful, but Halls pro-Northern point of view, coupled with his sequential approach, makes it less valuable than it might otherwise have been.

The Maps of Gettysburg: An Atlas of the Gettysburg Campaign, June 3 July 13, 1863 takes a different approach on two levels. First, its neutral coverage includes the entire campaign from both points of view. The text and maps carry the armies from the opening step of the campaign during the early days of June all the way to the battlefield in Pennsylvania, through the three days of fighting, and then south again until the Army of Northern Virginia crossed the Potomac River in mid-July. My purpose is to offer a broad and full understanding of the complete campaign, rather than a micro-history of one day or one sector of the battle itself.

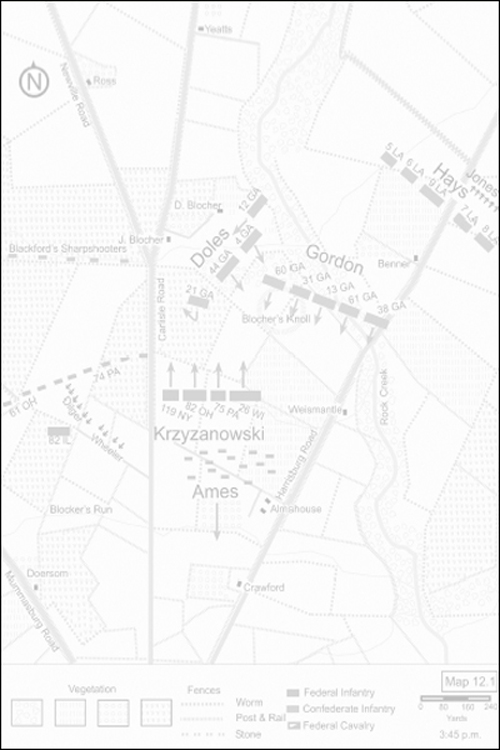

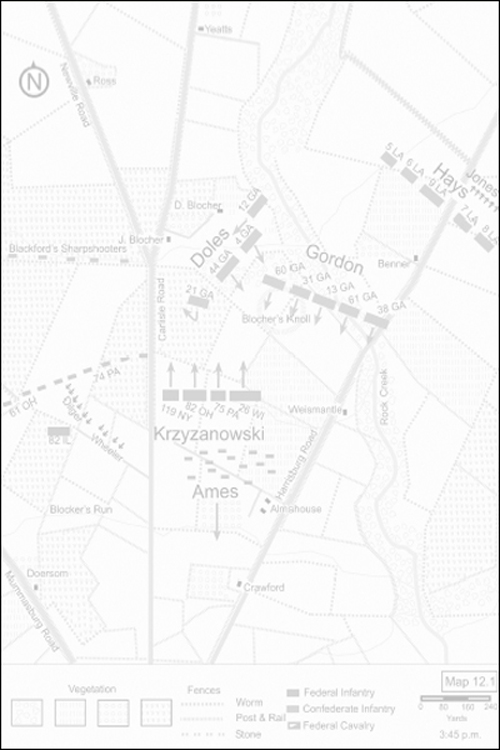

Second, The Maps of Gettysburg dissects the actions within each sector of the battlefield for a deeper and hopefully more meaningful experience. Each section of this book includes a number of text and map combinations. Every left-hand page includes descriptive text corresponding with a facing right-hand page original map. An added advantage of this arrangement is that it eliminates the need to flip through the book to try to find a map to match the text. Some sections, like the defeat of the 157th New York north of Gettysburg on July 1, are short and required only two maps. Others, like the prolonged bloody combat in the Wheatfield on July 2, required a large number of maps and text pages. Wherever possible, I utilized relevant firsthand accounts to personalize the otherwise straightforward text.

To my knowledge, no single source until now has pulled together the myriad of movements and events of this mammoth campaign and offered it in a cartographic form side-by-side with reasonably detailed text complete with end notes. I hope readers find this method of presentation useful. Newcomers to Gettysburg should find the plentiful maps and sectioned coverage easy to follow and understand. Hopefully, it makes digesting what is an otherwise complex campaign easier to grasp in its broad strokes. The various sections may also trigger a special interest or two and so pry open avenues for further study. I am optimistic that readers who approach the subject with a higher level of expertise will find the maps and text not only interesting to study and read, but truly helpful. If someone, somewhere, places this book within reach to refer to it now and again as a reference guide, the long hours invested in this project will have been worthwhile.