LEES LAST

CAMPAIGN

LEES LAST

CAMPAIGN

THE STORY OF LEE AND HIS MEN

AGAINST GRANT 1864

Clifford Dowdey

Skyhorse Publishing

Copyright 1960 by Clifford Dowdey

Copyright renewed 1999, 2011 by Carolyn Dunaway

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dowdey, Clifford, 1904-1979.

Lees last campaign : the story of Lee and his men against Grant, 1864 / Clifford Dowdey.

p. cm.

Originally published: Boston : Little, Brown, 1960.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61608-411-0 (alk. paper)

1. Virginia--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Campaigns. 2. Confederate States of America. Army of Northern Virginia. 3. Lee, Robert E. (Robert Edward), 1807-1870. 4. Grant, Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 1822-1885. 5. United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Campaigns. I. Title.

E470.2.D73 2011

975.503--dc23

2011018080

Printed in the United States of America

For

John A. S. Cushman

and

Ivan von Auw, Jr.

Contents

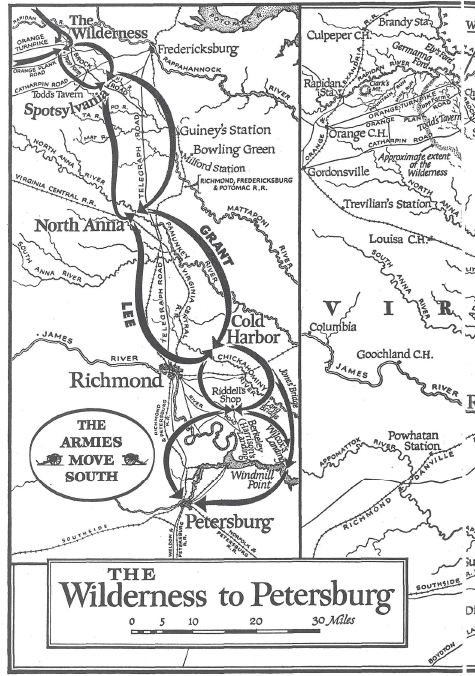

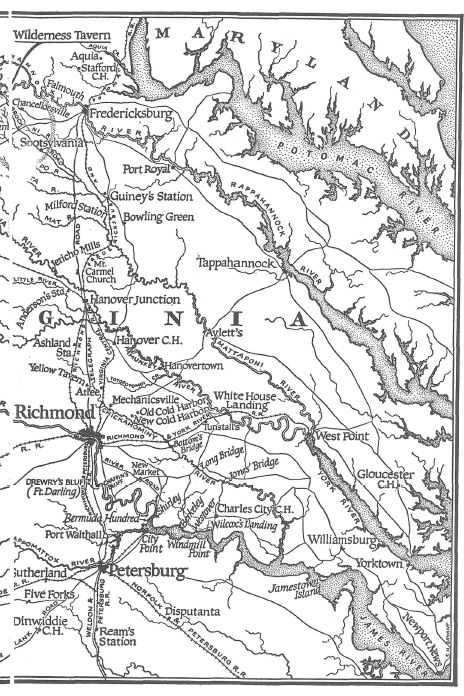

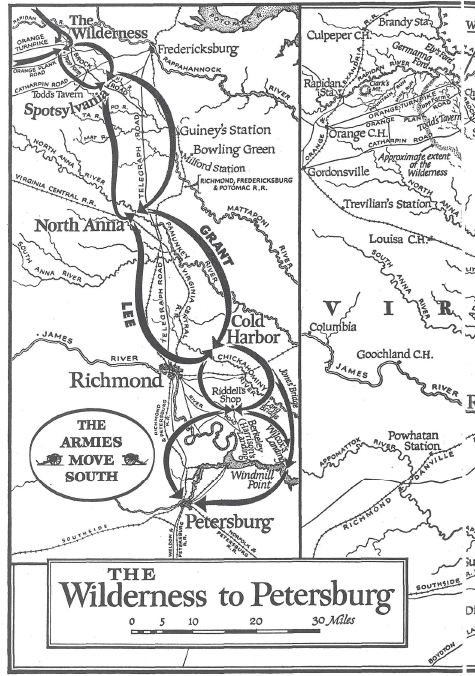

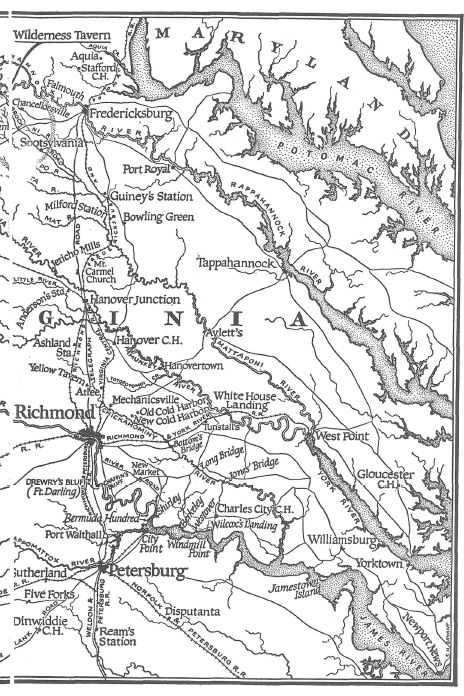

Maps

PART ONE

One Against the Gods

CHAPTER ONE

The Weight of Empire

I N THAT SPRING the pageantry was not yet, not quite, gone from the war. Through all privations, general officers in Lees army managed to turn themselves out well. Though the cadetgray cloth of their uniforms was usually no more than a thread through the motley of the soldiers makeshifts, when seen in a group, the generals still suggested the panoply of the chivalric tradition.

On May 2, 1864, the high command of the Army of Northern Virginia formed such a spectacle for the first time since Gettysburg, the year before, and for the last time in their lives. Full-bearded, booted and spurred, with gauntleted hands resting on sword hilts and buttons gleaming on double-breasted coats, the generals stood near their saddled horses like the figures in old lithographs and murals. Even the background, a mountaintop in spring, was almost an idealized setting.

April had been a rainy month, and May came with a sudden flowering of the countryside. Grass and leaves turned freshly green, buds were opening, honeysuckle and dogwood grew in the forests, and purple violets along the roadside. Clarks Mountain was not much of an eminence in itself but, in a generally flat countryside averaging less than 500 feet above the tide, its 1100 feet gave the hill a commanding position. From there Lee and his generals surveyed, across the Rapidan River and beyond the devastated farmland of middle Virginia, the endlessly stretching tented city of the enemy.

Soldiers from the mountain signal station had earlier reported stirrings in the Federal camp. And on that Monday in May, General Lee came for a personal look.

Since November the two armies had camped on opposite sides of the brownish stream, waiting for spring. The Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia had fought one another on so many fields that, like two old rivals, each was thoroughly familiar with the potential and the habits of the other. Every soldier in the camps understood as clearly as generals, more clearly than members of their governments, that the invading army waited for spring to attack across the river in the most concentrated blow yet delivered at the Confederate citadel, and that Lees smaller, physically declining army could only wait for the blow to fall.

Waiting, as General Lee said, on the time and place of the enemys choosing was galling to his nature as a man and antithetical to his principles of warfare. By the fourth year of the war, the resources of the Confederacy had been strained too thin to permit any alternative. Lees only hope lay in outguessing the opponent and trying to catch the heavily weighted columns at a disadvantage.

From all he revealed, by word or expression, General Lee never appeared more sure of himself than on that second day of May. The General seemed in better health with the turn in the weather and the prospect of action. During the winter he had suffered from rheumatic pains and frequently expressed his physical incapacity. A strongly built and superbly conditioned man, normally possessed of great endurance, his decline had begun the year before. In March of 1863 he had come down with a severe throat infection, his first recorded illness during the war. This was accompanied by what was then diagnosed as a rheumatic attack, but which was probably acute pericarditis. His complexion was florid and he suffered from hypertension which, along with angina pectoris, was to cause his final illness.

Though Lee was unaware of such subsurface undermining as a heart condition, he had visibly aged at fifty-seven. The classically handsome face of 1861, clean-shaven except for a dark mustache, had become the gray-bearded image of the patriarch. His thinning hair, which had gone from brown to gray, was turning white where it fluffed out over his ears. To the men sharing common cause with him, this patriarchal figure was the Uncle Robert or Mister Robertslurred to Marse who rode among them, erect and composed, on the familiar Traveler.

General Lee kept other horses at headquarters during the war, but the seven-year-old Traveler became the favorite of them all. General Lee called him a Confederate gray, with black mane and tail. A finely proportioned and strongly built middle-sized horse, his feet and head were small, and he was distinguished by a broad forehead and delicate ears. Though he had a smooth canter and a fast, springy walk, Traveler liked to go at a choppy trot, which was harder on a rider than Lees horsemanship made it appear. He had been with Lee since before the General assumed command of the army in June, 1862, and was inseparably associated with Lee in the Army of Northern Virginia. The pair of them was like a symbol of indestructibility, a reassuring quality that existed outside the mutations of time and circumstance.

This response to the aura of Lee was not only a product of his spectacular successes. At the time of his emergence in the summer of 1862, Hampden Chamberlayne, a scholarly young Richmond lawyer serving with a howitzer battery, wrote his sister: When by accident at any time I see Gen. Lee, or whenever I think of him, whether I will or no, there looms up to me some king of men, superior by the head, a gigantic figure on whom rests the world,

With Atlantean shoulders fit to bear

The weight of empire.

The world of the generals who gathered around Lee on that May Monday was placed on those Atlantean shoulders in the simplest directness of discipleship. In unquestioning acceptance of Lee as their leader, rather than as commanding general in a chain of command, his subordinates recognized their role as that of followers. The men could be jealous among themselves, and some used all the customary methods for personal advancement, but there was never any of the angling for army command that characterized the politically dominated Army of the Potomac. This was one of the reasons that the officially designated Army of Northern Virginia entered the peoples language as Lees army or, as an old country lady called it that spring, Mr. Lees Company.

Next page