CAMPAIGN 274

SHENANDOAH 1864

Sheridans valley campaign

| MARK LARDAS | ILLUSTRATED BY ADAM HOOK |

Series editor Marcus Cowper

CONTENTS

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

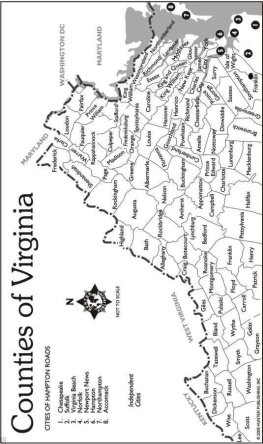

The Union and the Confederacy battled over the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia for three years. Nestled between the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Valley and Ridge Appalachians to the west, the valley served as granary for General Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia, providing bread and beef to feed this shield of the Confederacy, and fodder and remounts for its cavalry. The reinforcements that turned the tide at the First Battle of Bull Run (or First Manassas) on July 21, 1861 and yielded a Confederate victory came from the Shenandoah. In addition, the Shenandoah formed a sheltered highway to the north for the forces of the Confederacy during their invasion of Maryland in 1862 and Pennsylvania in 1863.

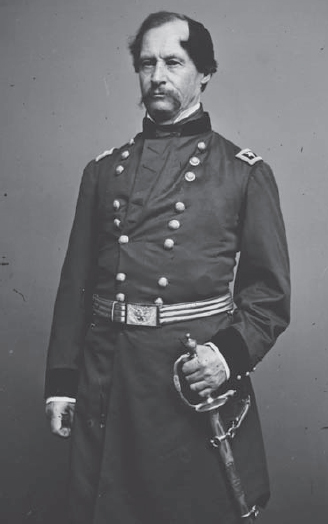

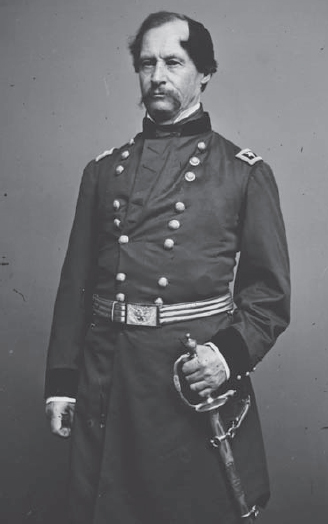

When General Philip Sheridan was given tactical command of Union forces in the Shenandoah in August 1864, general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant asked Major-General David Hunter (below) to serve as Sheridans superior, in an administrative role. Hunter refused, preferring a field command. (LOC)

The Union tried to wrest control of the valley from the Confederacy in 1862. Its forces took the northern half of the valley, even beating the Confederates commanded by the vaunted Thomas Stonewall Jackson at the First Battle of Kernstown on March 23. Jackson then outhustled three Union armies and ignominiously chased them from the Shenandoah. His infantry moved so quickly that thereafter they were called Jacksons Foot Cavalry.

The Union was so badly beaten they all but left the Shenandoah alone in 1863. In 1864 the United States Armys new general-in-chief, Ulysses S. Grant, created the Unions first cohesive strategy for conquering the Confederacy. Its primary goal was the destruction of the Confederate field armies. Geographic objectives only existed to the extent that they supported this mission. The Shenandoahs role in feeding Lees forces reinstituted its strategic importance for the Union; taking the valley would starve the Army of Northern Virginia into submission. Two Union armies advanced into the Shenandoah in the spring of 1864: one came over the Appalachians from West Virginia, while the second marched from the mouth of the Shenandoah river at Harpers Ferry.

Grants initial plans came a cropper. In early July 1864 Lee sent a corps under the command of Lieutenant-General Jubal Early to counter the Union invasion of the Shenandoah Valley. In a brilliant six-week campaign, Early first drove Union forces out of the valley, and then launched the last Confederate invasion of the Union states, moving his independent command into Maryland and marching to the gates of Washington DC.

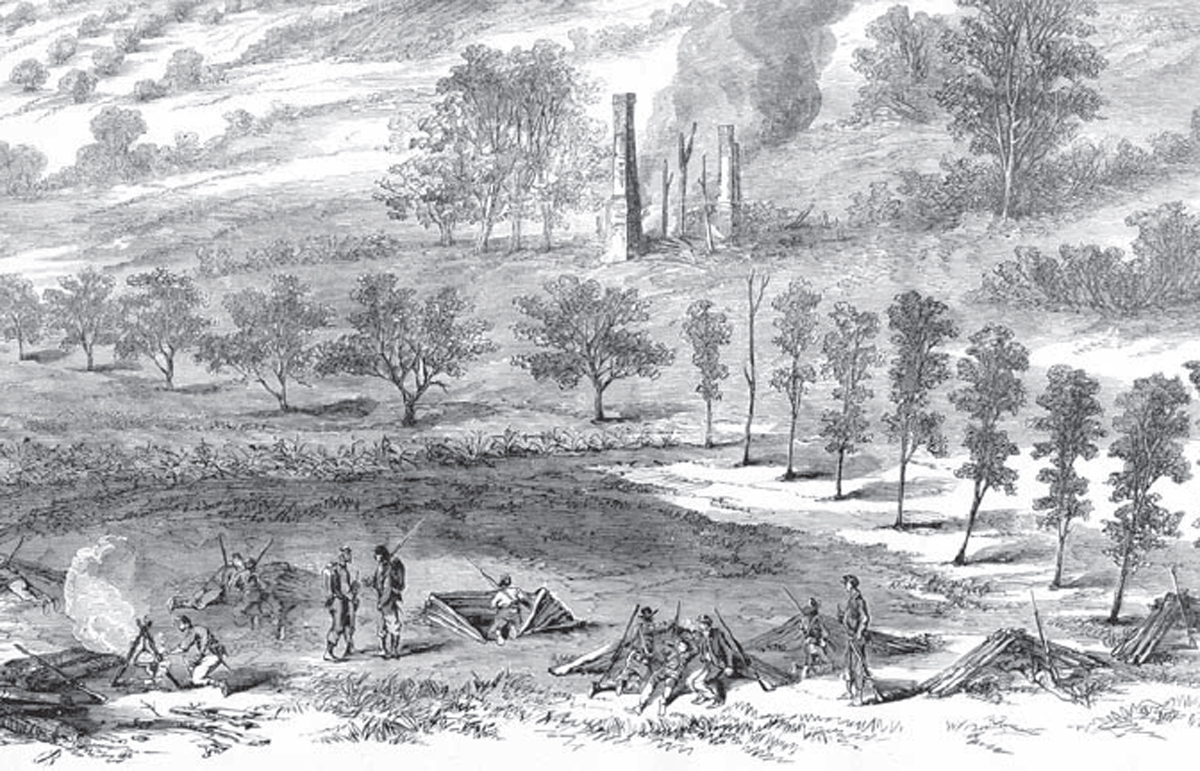

Although the raid caused panic in Washington, Early lacked the forces to overcome the determined defense and capture the capital. Moroever, few in the North realized how weak Earlys forces really were. Jubal Early continued his game of hitting the North at unexpected spots. He marched into Pennsylvania and burned Chambersburg in late July 1864. Before the North could react, he returned to the Shenandoah Valley.

Grant was forced to transfer a corps from the Army of the Potomac, then besieging Petersburg, Virginia to the District of Columbia. He was unhappy about the loss of troops, the failure to control the Shenandoah and particularly about Earlys ability to raid the North with impunity. Grant created a new command on August 1, 1864, adding the reinforcements sent to the Union forces in Washington (who had previously been chased out of the Shenandoah) to form the Union Army of the Shenandoah.

Grant realized that defeating Early was less a matter of troops than of leadership. The Union commanders that had already clashed with Early in the Shenandoah ValleyFranz Sigel and David Hunterhad both had sufficient numbers of men to defeat him. However, both lacked the necessary military and leadership skills required for victory. Grant needed someone capable of taking charge of the resources already in the vicinity of the Shenandoah and of achieving the right results.

After chasing Major-General Franz Sigels and Major-General David Hunters army out of the Shenandoah in the opening phase of the Valley Campaigns of 1864, Early took his independent command known as the Army of the Valley into Maryland, threatening Washington DC. His army turned back after reaching Fort Stevens, on the capitals outskirts. (AC)

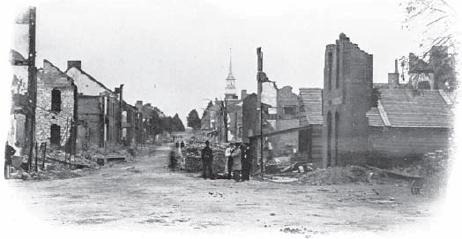

Following the Washington raid, Early marched into Pennsylvania to collect food and fodder for his army. During the sweep, the raiders burned the town of Chambersburg in late July 1864 in retaliation for Hunters burning of the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia in June. (AC)

At first Grant considered giving Major-General George Meade the assignment. However, reassigning Meade from his command of the Army of the Potomac was viewed as an undeserved demotion by Lincoln and other senior army officials. As a result, Grant decided against this. Instead, after considering several other candidates, Grant selected the cavalry commander Brigadier-General Philip Henry Sheridan.

It was a surprising choice. Sheridan, a 5ft 4in. bantam of a man, was a first-lieutenant in March 1861. Battlefield competence led to a meteoric rise from captain to major-general over a six-month period between 1862 and 1863 (with promotion to major-general in the regular army following in October 1864). Grant now wanted Sheridan take command of an army, putting Sheridan, then just 33 years old, on nearly the same level as William T. Sherman and George Meade.

Despite objections, Grant prevailed. Sheridan was sent to Harpers Ferry to take command of VI Corps (detached from the Army of the Potomac when Early raided Washington), two divisions of XIX Corps (reassigned from the Mississippi), and the corps-sized Army of West Virginia. Grants instructions to Sheridan were, simply, to put himself south of the enemy, and follow him to the death. Wherever the enemy goes, let our troops go also. Once started up the Valley they ought to be followed until we get possession of the Virginia Central Railroad.

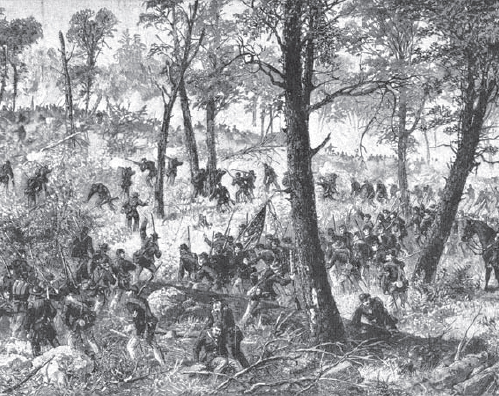

On August 7, 1864 Sheridan assumed command of the Army of the Shenandoah. Over the next 90 days two armiesthe Union forces led by Philip Sheridan and the Confederate troops commanded by Jubal Earlywould maneuver across the Shenandoah Valley. It would be a campaign of move and countermove, where unexpected attacks would be met by equally unexpected ripostes. In a series of changing fortunes, victory would turn into defeat, to be followed once again by victory.

The stakes were far higher than the fate of a disputed agricultural valley. The consequences of the campaign would be felt throughout a nation torn apart by civil war. Victory or defeat in the Shenandoah Valley would affect the outcome of the presidential election to be held in November 1864. It would affect the strength of the Confederate armies throughout the Confederacy. A Confederate loss of the valley would cripple the Army of Northern Virginia, which drew critical supplies from the area.

Next page