Students of the Civil War have long debated the relative importance of various military campaigns. Most attention has focused on the early summer of 1863, when Union armies won spectacular victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg, and the fall of 1862, when Southern armies mounted simultaneous offensives into Maryland and Kentucky. Gettysburg achieved early and enduring popular acclaim as the single decisive moment. A range of factors explains Gettysburgs primacy, among them its sheer magnitude, the fact that the battle occurred on Northern soil, the importance of the climactic assault on July 3 as a symbolic High Water Mark of the Confederacy, and Abraham Lincolns eloquent benediction over the graves of Union dead. The number of monuments at Gettysburg, as well as the crush of tourists at the battlefield park, testify to the battles hold on the American imagination.

Others have argued that Antietam rather than Gettysburg deserves recognition as the dividing line where Confederate fortunes shifted irrevocably toward defeat. Advocates of this view insist that never were so many political, diplomatic, and military elements aligned so favorably for the Confederacy. A victory in the hills of western Maryland or in southern Pennsylvania might well have propelled the South toward independence, but Lees retreat after the ferocious bloodletting at Antietam changed everything, causing Europe to back away from recognition and opening the door for emancipation and its vast consequences. Certainly no other battle exceeded the drama and tragedy of Antietam. Across more than two centuries of the nations involvement in wars of all kinds, Antietam remains the worst one-day slaughter in American history. The ghastly losses in the Cornfield, the West Woods, and the Sunken Road, the specter of the Confederacys premier army courting absolute disaster while pinned against the Potomac River, and the inexplicable refusal of the Federal commander to press his advantage supply powerfully haunting images.

Central to the campaign was a memorable military and psychological confrontation between Robert E. Lee and George Brinton McClellan. Interestingly, the respective leaders each occupied a somewhat uncertain position in his army. Just three months had passed since Lee took charge of the Army of Northern Virginia following Joseph E. Johnstons wounding at the battle of Seven Pines. In that time he had restructured the army, won impressive victories during the Seven Days and at Second Manassas, and taken his soldiers across the Potomac in a raid predicated largely on logistics. Despite Lees successes, however, he had not yet made the army his own; indeed, he operated in Maryland as a gifted and audacious stand-in pending Johnstons recovery. McClellans situation was considerably more tenuous. Relegated to a secondary role in Washington because of his failure on the Peninsula, he had been restored to field command in the critical days after Second Manassas. His genius at organization quickly brought order out of chaos, but he knew that Lincoln and the Republicans in Congress had little faith in him. Believing that any mistake might provide ammunition for political enemies to take his beloved Army of the Potomac away from him, McClellan moved with great caution, his attention divided between the need to counter the aggressive Lee and a desire for self-preservation.

Much recent sentiment concedes the dramatic nature of contests such as that between Lee and McClellan but plays down the importance of all military activity during the war. Although prodigiously wasteful of human life, say those who subscribe to this interpretation, none of the great battles really decided much. Civil War armies were simply incapable of dealing knockout blows, with the consequence that they usually grappled for a brief deadly moment before predictably withdrawing to prepare for the next confrontation. Influenced to a considerable degree by the frustrating American experience in Vietnam, this approach calls into question the value of the close study of Civil War campaigns. James M. McPhersons Battle Cry of Freedom (New York, 1988), in contrast, reaffirms the importance of armies and campaigns, isolating four critical times during the war when military events defined the eventual outcome. McPhersons quartet of turning points came in the summer of 1862 (Southern counteroffensives stopped the tide of Union success in the East and West), the autumn of 1862 (Northern armies repulsed Southern invasions at Antietam and Perryville), the summer of 1863 (Union victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chattanooga turned the tide toward final Northern victory), and the late summer of 1864 (Shermans success at Atlanta reversed growing Northern sentiment for a negotiated peace).

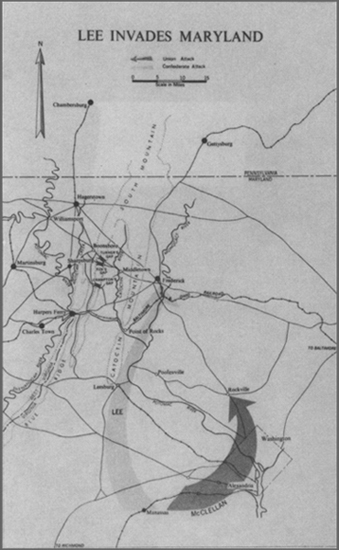

A debate thus continues on two levels. Were Civil War military campaigns important? And if so, what operations had the largest bearing on the course of the struggle? The essays below grew out of a conference on the Maryland campaign of 1862 held at the Mont Alto Campus of Pennsylvania State University in June 1988. The conference itself originated from a belief that the military events of late summer and fall 1862 were important, perhaps decisive. The authors sought to address a number of questions about the origins, conduct, and outcome of the campaign. Was Lees movement across the Potomac strategically sound? Did the Confederates have a reasonable chance of success? How did the leadership of each army perform? What were the critical moments of the campaign? What was the short- and long-term impact of the campaign?

These five brief essays make no claim to definitive answers. They are often speculative, and the authors, as readers will quickly discover, sometimes disagree. If the essays inspire some individuals to explore in more depth the 1862 Maryland campaign, or to think about some of its facets in new ways, they will have achieved their primary purpose.

Working with Bob Krick, Will Greene, and Dennis Frye at the Mont Alto conference and in putting this book together was a pleasure. Each of them combines in refreshing proportion enthusiasm, knowledge of their subjects, and a respect for deadlines. Eileen Anne Gallagher typed most of the manuscript, made her usual accurate suggestions for tightening prose, and gently encouraged me to use Sharpsburg rather than Antietam wherever possible. I thank them all for their humor and help with this project.