ALSO BY RICHARD SLOTKIN

NONFICTION

Regeneration through Violence:

The Mythology of the American Frontier, 16001860

(1973) (Albert J. Beveridge AwardAmerican Historical Association,

National Book Award Finalist, New York Times Notable Book of the Year)

So Dreadfull a Judgment: Puritan Responses to

King Philips War, 16751677 , with James K. Folsom (1978)

The Fatal Environment: The Myth of the Frontier in

the Age of Industrialization, 18001890

(1985) (Little Big Horn Associates Literary Award,

New York Times Notable Book of the Year)

Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier

in Twentieth-Century America

(1992) (National Book Award Finalist,

New York Times Notable Book of the Year)

Lost Battalions: The Great War and the

Crisis of American Nationality (2005)

No Quarter: The Battle of the Crater, 1864 (2009)

FICTION

The Crater (1980) (New York Times Notable Book of the Year)

The Return of Henry Starr ( 1988 )

Abe: A Novel of the Young Lincoln

(2000) (Michael Shaara Award for Civil War Fiction, Salon Best Book,

New York Times Notable Book of the Year)

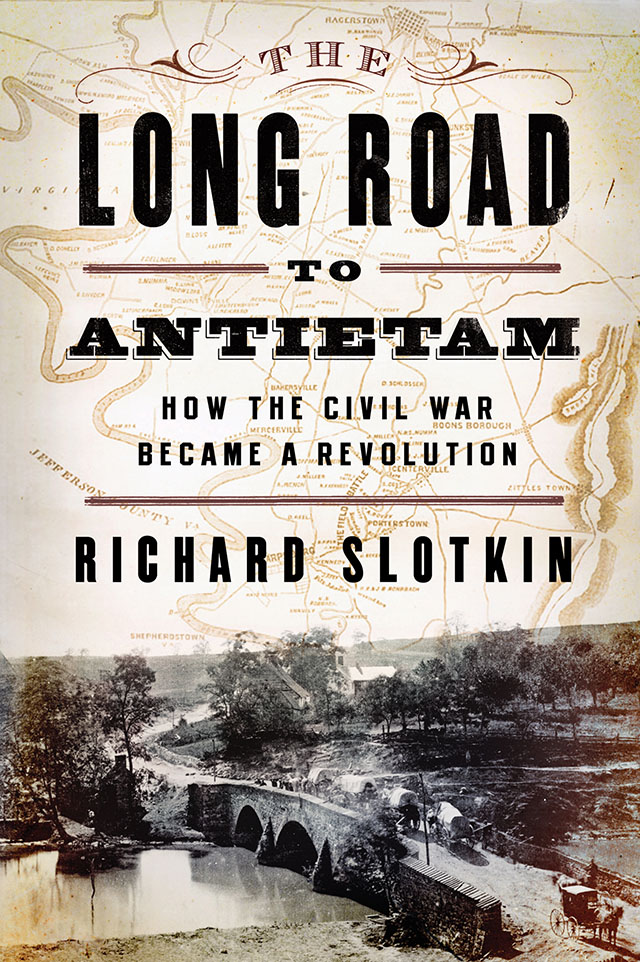

The

Long Road to

Antietam

HOW THE CIVIL WAR BECAME

A REVOLUTION

Richard Slotkin

L IVERIGHT P UBLISHING C ORPORATION

a division of

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY | NEW YORK LONDON

For Iris

CONTENTS

TURNING POINT: MILITARY STALEMATE

AND STRATEGIC INITIATIVES

LIST OF MAPS

INTRODUCTION

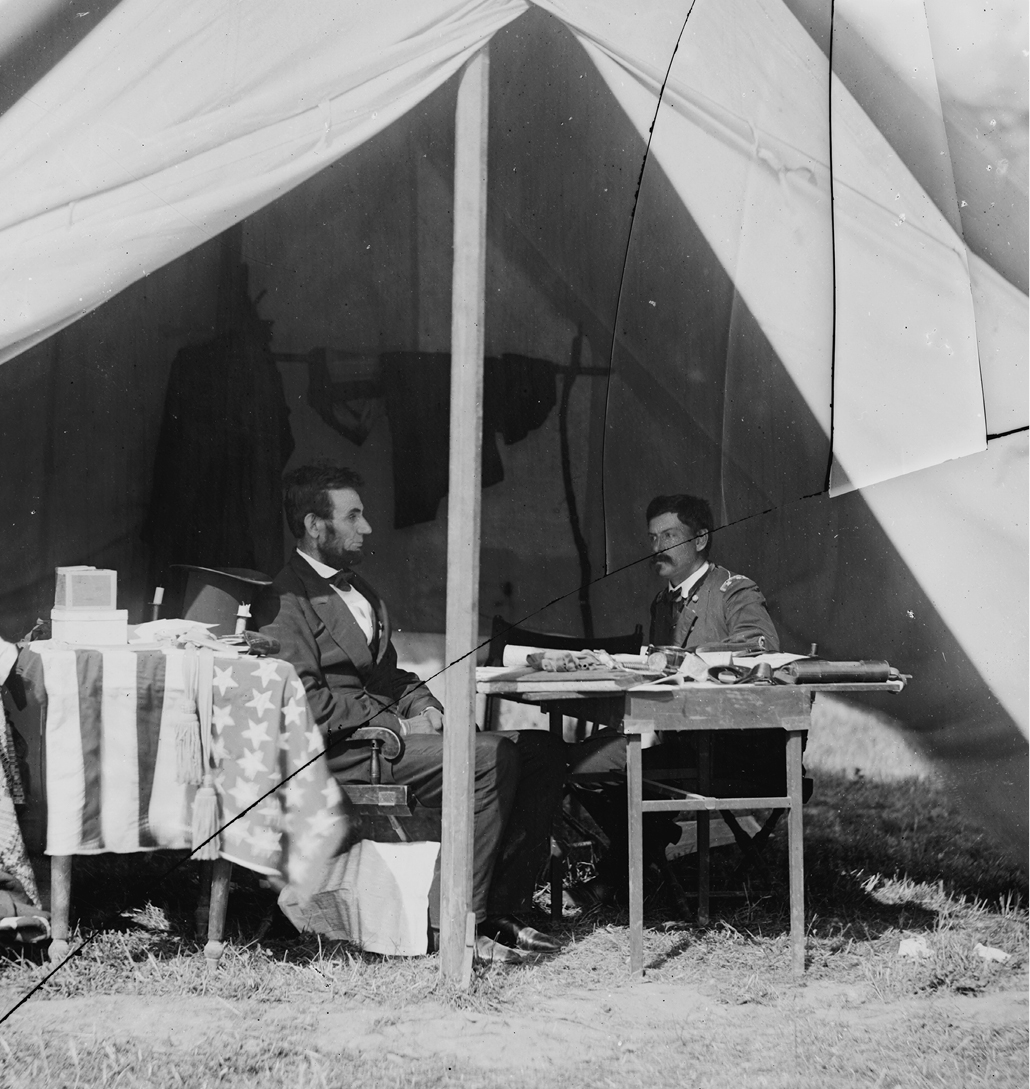

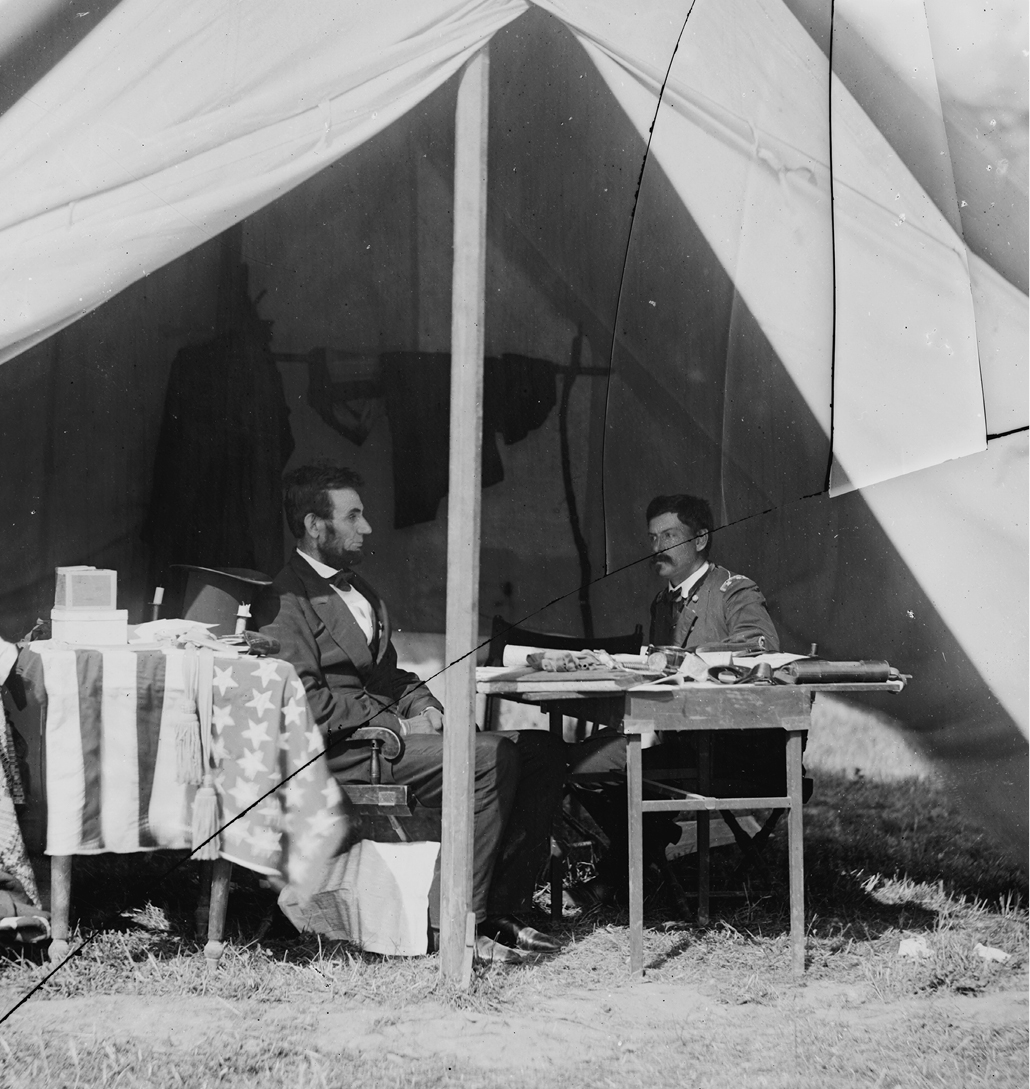

T HE BATTLE OF ANTIETAM HAS LONG BEEN CONSIDERED THE TURNING point of the Civil War. The defeat of Lees army frustrated the Confederacys best chance to win the war on the battlefield. The Union armys narrow victory on September 17, 1862, enabled Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, a political act that transformed the war and the future of United States by binding the defense of the Union to the destruction of slavery. Paradoxically, the victory also allowed Lincoln to fire the man who won the battle, Major General George McClellan, and thereby begin the military reorganization that would in the end produce victory for the Union.

In fact, neither the military nor the political results of the battle were decisive. The military strength of the Confederacy was not substantially weakened by the defeat. The political and military benefits of emancipation would prove substantial, perhaps decisive, in the long run. But in the shorter term the costs offset the benefits. Emancipation gave the disorganized Democratic opposition an issue around which to rally: the defense of White supremacy. And although the presidents proclamation made it more difficult for the British to recognize the Confederacy, the policy of Lord Palmerstons government was ultimately determined by a hardheaded calculation of the Confederacys military prospects. In short, after Antietam the outcome of the war was still uncertain and would hinge on policies not yet enacted and battles still to be fought.

The significance of Antietam lies not in the battle itself but in the campaign that produced it. That campaign was the result of a radical turn in the strategies of both Union and Confederacya series of political and military decisions made over a four-month period in the summer and fall of 1862 that transformed the policies, principles, and purposes that had hitherto governed the conduct of the war. Before Antietam it was still possible for Americans to imagine a compromise settlement of sectional differences. After Antietam, and the Emancipation Proclamation, the only way the war could end was by the outright victory of one side over the other. Either way, the result would be a revolutionary transformation of American politics and society.

The road to Antietam, however, began long before September 3, 1862, when General Lee gave orders for the invasion of Maryland. It had, in fact, begun nearly two months earlier, during the first two weeks of July, whenafter six months of intense military engagement by land and naval forces all around the Confederate peripheryPresidents Lincoln and Davis were compelled to acknowledge that their existing strategies were incapable of producing decisive results, and that new and more radical policies were necessary.

STRATEGY IS MORE than the mechanics of military operations. All war is a form of politics, in which force and violence substitute for the civil exercise of power. That is especially true of the American Civil War, which was not fought over territory but over fundamental questions of social order, political organization, and human rights. Through strategic planning, the leaders of the warring parties define the aims and purposes of the conflict and develop a combination of political actions and military operations designed to control the action and achieve their objectiveswhich are always ultimately political.

Of course, strategy is not everything in war or politics. It is a truism of military science that no strategic or tactical plan outlives the first actual combat. The Antietam campaign is a pluperfect illustration of that maxim, in that almost nothing about it went as its planners intended. Presidents and generals cannot control the course of events that their orders may initiate. Their purposes and intentions will be crossed by those of their opponents and complicated by the motives and commitments of the people who do the actual fighting and the civilian societies that support or fail to support the war effort. Nevertheless, in modern warfare the role of a nations political and military leadership is central. The ideas and intentions of these individuals shape the decision whether, when, and how to go to war or organize a campaign; their commands set the action in motion, determine its initial lines of operation, and set the conditions under which the conflict will begin. In studying the thoughts and actions of presidents and generals we gain insight into the motives and values that make wars and help to determine their course.

While it is easy to see how politics shapes strategy through the whole course of a war, it is harder to trace the connection between politics and the tactical decisions that shape war at the operational level. Thus most histories of the Antietam campaign treat the political decisions of the rival presidents and the operational decisions of their generals as if these occurred in separate spheres of thought and actionoverlapping at the edges, but essentially different. Historians generally acknowledge that the outcome of the Battle of Antietam was given a vital political significance when Lincoln used the Unions narrow victory as the occasion to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. But in fact political concerns and priorities shaped the operational decision making of both presidents, and of their army commanders, at every stage of the campaign; and the interaction of politics with military operations drove leaders on each side to adopt increasingly radical and even revolutionary policies. The Long Road to Antietam differs from previous studies of the campaign in that it offers a narrative that integrates military and political developments and shows how each played with and against the other as events unfolded.

Next page