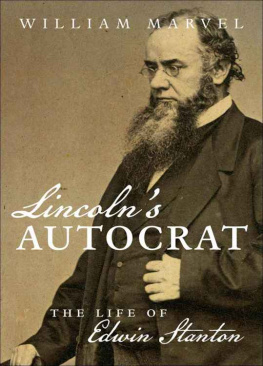

Lincolns Autocrat

Civil War America

PETER S. CARMICHAEL, CAROLINE E. JANNEY, and AARON SHEEHAN-DEAN, editors

This landmark series interprets broadly the history and culture of the Civil War era through the long nineteenth century and beyond. Drawing on diverse approaches and methods, the series publishes historical works that explore all aspects of the war, biographies of leading commanders, and tactical and campaign studies, along with select editions of primary sources. Together, these books shed new light on an era that remains central to our understanding of American and world history.

Lincolns Autocrat

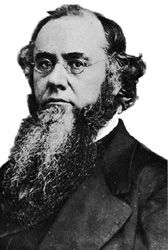

The Life of Edwin Stanton

William Marvel

The University of North Carolina Press

Chapel Hill

2015 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Set in Miller and Clarendon by codeMantra

Manufactured in the United States of America

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

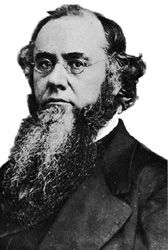

Jacket illustration: Edwin M. Stanton in the summer of 1865 (courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society).

Title page photograph of Edwin M. Stanton: Dover Publications (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society).

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marvel, William.

Lincolns autocrat : the life of Edwin Stanton / William Marvel.

pages cm. (Civil War America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4696-2249-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4696-2250-7 (ebook)

1. Stanton, Edwin M. (Edwin McMasters), 18141869. 2. Cabinet officersUnited StatesBiography. 3. United States. War DepartmentBiography. 4. StatesmenUnited StatesBiography. 5. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Biography. 6. Reconstruction (U.S. history, 18651877)Biography. 7. United StatesPolitics and government18611865. 8. United StatesPolitics and government18651869. 9. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Friends and associates. I. Title. II. Title: Life of Edwin M. Stanton.

E467.1.s8M37 2015

973.7092dc23

[B]

2014032690

For Nell

CONTENTS

MAPS & ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

Washington, D.C., in Stantons Time

The East

The West

ILLUSTRATIONS

A section of illustrations follows page

His heart was full of tenderness for every form of suffering and sorrow, and he always had a word of sympathy for the smitten and afflicted.

Senator Henry Wilson, Edwin M. Stanton, Atlantic Monthly, February, 1870

He cared nothing for the feelings of others. In fact it seemed pleasanter to him to disappoint than to gratify.

Ulysses S. Grant on Stanton, Personal Memoirs

It will be regretted by the impartial historian of the future that Stanton was capable of impressing his intense hatred so conspicuously upon the annals of the country, and that Lincoln, in several memorable instances, failed to reverse his War Minister when he had grave doubts about the wisdom or justice of his methods.

Alexander K. McClure, Abraham Lincoln and Men of War-Times

Edwin Stanton was never falseto a principle of truth, honesty, justice, or honor!

Pamphila Stanton Wolcott on her brother, unpublished memoir

Stanton is, by nature, an intriguer, courts favor, is not faithful in his friendships, is given to secret, underhand combinations.

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles, diary entry of December 20, 1862

Mr. Stanton... believes in mere force, so long as he wields it, but cowers before it, when wielded by any other hand.

Ex-Attorney General Edward Bates, diary entry of May 25, 1865

He was always on my side & flattered me ad nauseam.

James Buchanan to Harriet Lane, January 16, 1862

Stanton... has no sincerity of character, but is hypocritical and malicious.

Orville Hickman Browning, diary entry of February 15, 1867

PREFACE

In the century after his death, Edwin Stanton became the subject of five published biographies. The best known of these is Harold M. Hymans Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincolns Secretary of War, which was begun by Benjamin H. Thomas. Thomas died in 1956 with the project unfinished, and Hyman took it up by 1958, graciously giving primary title-page credit to Thomas when the book was published in 1962. For more than half a century Hyman has stood as the principal authority on Stanton, whom he characterized as a devoted patriotbrusque and quirky, but compulsively truthful and dedicated to his vision of justice and the common good. That view has guided much of the subsequent historical literature, and colored most of it.

Hyman was the most objective of the biographers, but even he favored Stanton visibly, often giving him the benefit of the doubt when the sources appeared to dictate otherwise. Hyman leaned toward generous interpretations of episodes that raised serious questions about Stantons integrity, and occasionally he presented negative sources in a positive light, often by missing obvious sarcasm. His tendency to overlook or discount Stantons administrative mistakes and his failure to assess the impact of Stantons divisive departmental and interdepartmental scheming undermines Hymans complimentary estimate of Stantons service in three administrations. Hyman apparently did not consider that Stanton might have misrepresented James Buchanan in order to ingratiate his new Republican friends, or that his battle with Andrew Johnson served his own interests.

Frequent misreading of the evidence may have reflected the posthumous handoff of Thomass notes, which predated the era of photocopiers. That offered abundant opportunity for accumulated misunderstanding, which seems rife in Hymans biography, where errors and omissions run from the amusing to the disturbing. In one instance, because of a correspondents colloquial reference to dropping in on the Macy tribe on Nantucket, Hyman supposed that Stanton visited an Indian village instead of the Quaker Macy family from which he was descended. Elsewhere, Hyman asserted that Stanton feared Johnson wanted to use the U.S. Army to suppress Congress, but he documented that claim with two letters from Oliver Morton and John Pope that have no relation to so alarming a prospect. In 2009 David Stewart repeated Hymans unsupported claim more stridently in his book on Johnsons impeachment, demonstrating the general danger of relying on secondary sources for factual information and illustrating how Hymans book has distorted the interpretation of that era over the past half-century. Scores of documentary discussions of such errors, amounting to a small book by themselves, have been removed from the notes in the editing process because of their sheer volume.

The lenience of Hymans treatment inevitably exaggerates any contrast with a critical portrait, and many who have been influenced by his biography will think me too harsh on Stanton. The preponderance of testimony suggests that, at least in his public life, Stanton tended to be insincere, devious, and dedicated to self-preservation: some of the evidence comes from acquaintances who were not hostile to him, or who were even friendly, and some is in his own hand. When studied with the skepticism that is as important in history as it is in journalism, Edwin Stantons legacy shines less brightly, suggesting a need to reexamine his relations with those near him. Stantons close collaborator, Joseph Holt, seems undeserving of the gleaming armor he wore in Elizabeth Leonards recent biography, while Stantons assistant secretary, Charles Dana, comes away tainted with unbecoming portions of self-interest, hypocrisy, and vindictiveness. President Lincolns association with Stanton endures a measure of reappraisal, as well.

Next page