Published in 2017 by Enslow Publishing, LLC 101 W 23rd Street, Suite 240, New York, NY 10011

Copyright 2017 by Deborah Kent

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kent, Deborah, author.

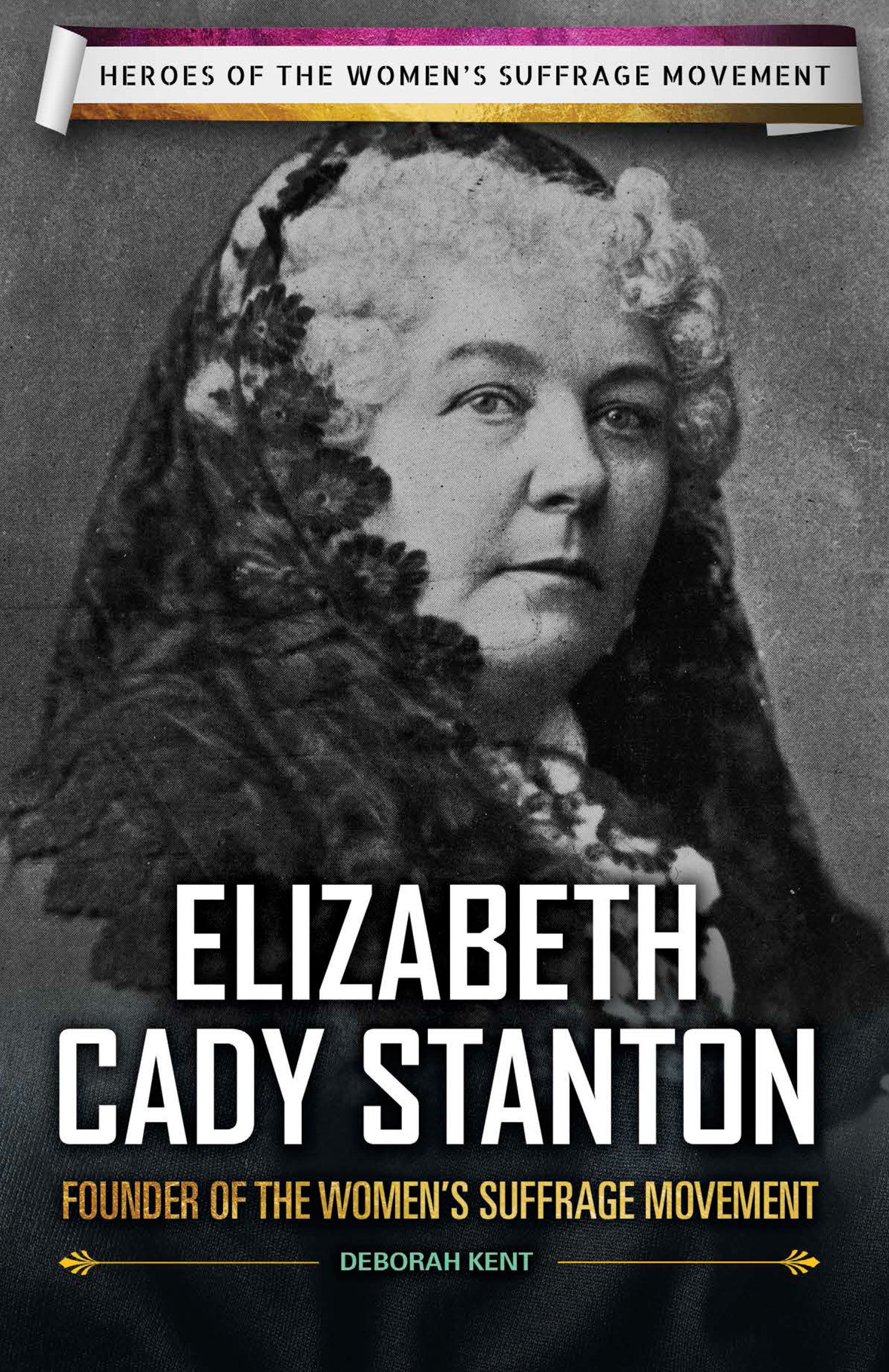

Title: Elizabeth Cady Stanton : founder of the womens suffrage movement /Deborah Kent.

Description: New York, NY : Enslow Pub., 2017. | Series: Heroes of the womens suffrage movement |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050611 | ISBN 9780766078895 (library bound)

Subjects: LCSH: Stanton, Elizabeth Cady, 1815-1902Juvenile literature. | SuffragistsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. | FeministsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. | WomenSuffrageUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HQ1413.S67 K4638 2016 | DDC 305.42092dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015050611

Printed in the United States of America

To Our Readers: We have done our best to make sure all website addresses in this book were active and appropriate when we went to press. However, the author and the publisher have no control over and assume no liability for the material available on those websites or on any websites they may link to. Any comments or suggestions can be sent by e-mail to .

Portions of this book appeared in the book Elizabeth Cady Stanton: Woman Knows the Cost of Life.

Photo Credits: Cover, Time Life Pictures/Mansell/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images; cover, interior design elements: wongwean/Shutterstock.com (grunge background on introduction, back cover); Attitude/Shutterstock.com (purple background); Sarunyu_foto/Shutterstock.com (white paper roll); Dragana Jokmanovic/Shutterstock.com (gold background); Eky Studio/Shutterstock.com (grunge background with stripe pattern); macknimal/Shutterstock.com (water color like cloud); Borders-Kmannn/Shutterstock.com (vintage decorative ornament); p. 5 Private Collection/Wood Ronsaville Harlin, Inc. USA/Bridgeman Images; p. 10 Fotosearch/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 12 Universal History Archive/UIG/ Getty Images; p.

15 Seneca Falls Historical Society; p. 19 Reproduced with the permission of The Historical Society of the Courts of the State of New York and its website: www.nycourts.gov/history . Any other use of this material is strictly prohibited; pp. 25, 29, 47, 56, 67, 84, 104, 107, 108 Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Collection; p. 33 Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 34 F Gutekunst/File:Lucretia Mott. 275011.jpg/Wikimedia Commons; pp. 38, 62, 79 Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com; p. 41 National Park Service; p. 44 Interim Archives/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 51 Kean Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 66 Anthony, Susan B./File:Petition of E. Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and others (1865)jpg/Wikimedia Commons; p. 72 MPI/Archive Photos/Getty Images; pp. 76, 97 Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty images; p. 87 Picture History/Newscom; p. 91 Napoleon Sarony/File:Napoleon Sarony -Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony - Google Art Project-cropped.jpg/Wikimedia Commons; p.

93 Ph.Glusacks/File:Elizabeth Cady Stanton before the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections cph.3b08655.jpg/Wikimedia Commons; p. 110 Barbara Freeman/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

A bigail Adams spent the spring of 1776 at home in Braintree, Massachusetts, cooking, cleaning house, and caring for her children. Her husband, John Adams, was away in Philadelphia, where he served as a member of the Continental Congress. The thirteen American colonies were on the brink of declaring independence from Great Britain.

[I]n the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make I desire you would remember the ladies, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband on March 31.... Remember all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies we are determined to foment a revolution.

John Adams did not take his wifes suggestion seriously. He dismissed it as a joke and apparently gave it no further thought. Neither the Declaration of Independence nor the original US Constitution made any mention of the rights of women.

Laws in the young United States were modeled closely upon the laws that had evolved in England for over more than five hundred years. In 1765, Sir William Blackstone, a noted English legal scholar, described the status of married women: The very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, married women in the United States could not sign contracts or inherit property. If a couple divorced, the wife lost custody of the children. In addition, women could not serve on juries, hold public office, or vote.

The options for women were seriously limited in other ways as well. Women had no access to higher education, and they were barred from entering most professions. It was considered improper for a woman to speak at a gathering of both women and men. The vast majority of women married in their teens or early twenties and stayed at home for the rest of their lives, caring for their children and husbands.

Yet fresh ideas whispered in the minds of women and men in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and beyond. If all men were created equal, as the Declaration of Independence claimed, why were millions of human beings compelled to live in slavery? Since countless men squandered their earnings and their health at the taverns, why were there no laws to control the sale of liquor? And why did women have so few opportunities to use their talents?

The early decades of the nineteenth century are sometimes called the Age of Reform. Movements arose calling for the abolition of slavery and the closing of the taverns. Although they were banned from speaking in public, women took active roles in both of these movements. In 1833, Lucretia Mott, Sarah Mapps Douglas, and a group of other white and African American women established the Philadelphia Female Antislavery Society. In 1837, Angelina Grimke of South Carolina defied tradition and gave an antislavery lecture to an audience that included men. She opened the way for other women to speak in public.

In order to work more effectively for abolition and other causes, a growing number of women realized that they must secure suffrage, or the right to vote. In 1846, six women petitioned a constitutional convention in the state of New York, calling for women to be granted voting rights. The following year, Lucy Stone of Massachusetts set off on a lecture tour, speaking about womens rights to mixed male and female audiences.

At an early age, Elizabeth Cady Stanton became aware of societys injustices toward women. Her own experiences and the struggles of the women around her awakened her commitment to bring about change. At a time when a growing number of voices called for equal rights for women, including the right to vote, Cady Stanton emerged as a leader. In 1848, she helped organize the nations first womens rights convention. That convention, held in a church in Seneca Falls, New York, is regarded as a defining moment in the womens rights movement, the moment when the movement truly began.