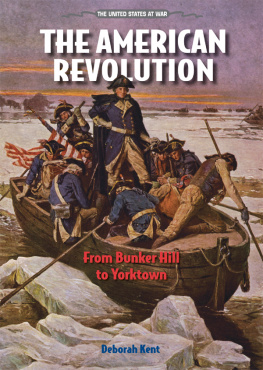

DONT FIRE UNLESS FIRED UPON. BUT IF THEY WANT A WAR, LET IT BEGIN HERE.

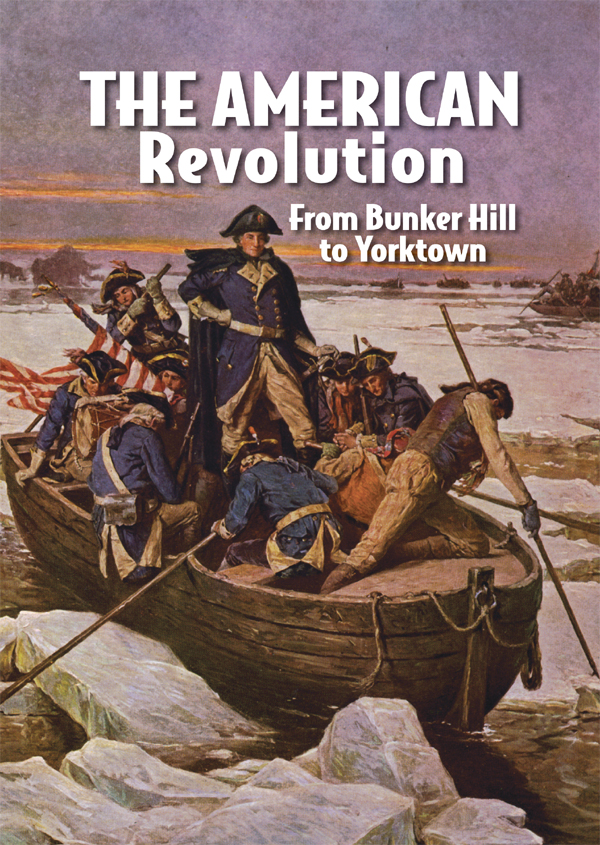

On April 19, 1775, Captain John Parker gave this order to the Lexington militia gathered at the village center to face the coming British soldiers. No one knows who fired first at Lexington, but that first shot signaled the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Only a year after the first battle, the American colonies declared their independence from Britain. But the struggle for freedom would cost the lives of many men and women. From the boycott of the Stamp Act to the final battle at Yorktown, author Deborah Kent examines the conflict that shaped a nation and introduced a new era of democracy to the United States.

About the Author

Deborah Kent received a BA from Oberlin College and a MSW from Smith College School for Social Work. She is the author of many fiction and nonfiction books for children.

Image Credit: The Granger Collection, New York

Growing up in New Jersey, I always felt that the American Revolution had taken place close to home. Washington crossed the Delaware River to win a battle at Trenton, our own state capital. He and his troops spent a cruel winter in Morristown. On a sweltering day in June, a woman called Molly Pitcher carried water for the Americans during the Battle of Monmouth. And only three miles from my house in Little Falls, I could walk along Rifle Camp Road, named in honor of the patriot troops who once pitched their tents in the nearby woods. The American Revolution seemed like a glorious erawhen people fought for the cause of freedom. Of course many diedbut they died the noble deaths of heroes.

I was shocked one day when my father declared that, if he had lived back in 1776, he would have been a Tory. I knew about the Tories, those colonists who had stubbornly remained loyal to the British throughout the war. They were turncoats, traitorsor were they?

Every question has two sides, or more. Like the rebellious colonists, the British soldiers and American Loyalists believed they fought for a cause that was honorable and just. Both sides had their moments of valor, and, on occasion, both committed appalling atrocities. In every battle, men on both sides suffered and died. No ideals, however noble, softened the pain inflicted by musket balls and slashing bayonets.

Like most wars, the American Revolution could not be contained once it had begun. It swelled into a major conflict that spanned six long, bloody years. It stretched beyond the thirteen rebelling colonies to reach the American frontier and even the West Indies. Other countriesFrance, Spain, and Hollandwere eventually swept into the fighting.

It must have been hard to remember ideals as battle casualties mounted and smallpox and other diseases ravaged the military camps. Yet in the end, after the last roar of the cannon faded, a new nation emergedone rooted in the ideals of democracy, a belief in government for the people, by the people. Over the last three centuries, the democratic principles that the American Revolution set in motion still echo around the world. These ideals, which shook the lives of thousands of men and women more than 225 years ago, are indeed still very close to home.

1

THE SHOT HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

WHAT A GLORIOUS MORNING FOR AMERICA!

Samuel Adams, on hearing gunfire at Lexington, April 19, 1775

The British were taking no chances. The officers shook the men awake instead of rousing them with the usual shouts and bugle calls. There was no talking as the troops gathered in the darkness on Boston Common. The march got underway. When the men reached a brook, they waded acrossthe stamping of army boots on the hollow planks of the wooden bridge would have alerted people in the neighboring farmhouses. General Thomas Gage had instructed his troops to move with the utmost secrecy. He wanted his soldiers to take the villages of Lexington and Concord completely by surprise.

Gage had learned that Samuel Adams and John Hancock, two ringleaders in the growing unrest among the American colonists, were staying at a house in Lexington. As long as they were at liberty, Gage feared that peace could not be restored. Gage ordered his men to capture the two troublemakers. Then they were to march on to Concord and seize American stores of guns and ammunition. If all went well, the rebellion could be put down in a single nights work.

Image Credit: Steven Wynn / iStockphoto

Samuel Adams

For more than ten years, tension had been mounting between Great Britain and its thirteen American colonies. The city of Boston had become the hub of American protest against British control. And by April 18, 1775, when Gages troops set out for Lexington, Boston was a city under siege. British soldiers patrolled the streets, and British warships blockaded the harbor. Most Bostonians resented the outsiders, and some were determined to fight back.

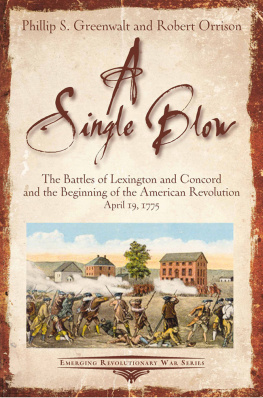

Every night that spring, colonial spies observed the comings and goings of the British troops and listened hungrily to every scrap of conversation. Even before the troops mustered on Boston Common, the Americans knew what Gage planned to do. Two messengers on horseback galloped quickly toward Lexington with the news. Their names were William Dawes and Paul Revere.

Both Dawes and Revere rode at top speed, warning everyone along the way that the British were coming. Today, most Americans know about Paul Reveres ride, but few recognize Dawess name. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow immortalized Revere in a famous poem that begins, Listen, my children, and you shall hear / Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere. Because the name Revere rhymes more easily than the name Dawes, one man became a legend, while the other was nearly forgotten.

Eight colonial guards surrounded the house where Hancock and Adams slept. About midnight, Colonel Paul Revere rode up and requested admittance, Sergeant William Munroe wrote later: I told him the family had just retired, and had requested that they might not be disturbed by any noise about the house. Noise! he said. Youll have noise enough before long! The Regulars are coming out! We then permitted him to pass. With the advance warning, Hancock and Adams had plenty of time to slip away. Captain John Parker alerted his company of Lexington militiamen and gathered them on the village green.

In the meantime, the British got off to a slow start. They left Boston at 10 P.M. , crossing the Charles River into Cambridge. There, they waited more than two hours for provisions to arrive. At last, at 2 A.M. , they began the eighteen-mile march to Lexington.

Image Credit: Everett Collection

Paul Revere rides through a town on horseback warning the citizens that the British are coming