Contents

Guide

A hardcover edition of this book was published in 2000 by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

THE DAY THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION BEGAN . Copyright 2000 by William H. Hallahan. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

First Perennial edition published 2001.

Cover illustration by Charles C. J. Hoffbauer/SuperStock

The Library of Congress has catalogued the hardcover edition as follows:

Hallahan, William H.

The day the American Revolution began : 19 April 1775/

William H. Hallahan1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-380-97616-1

1. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 1775-1783. 2. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 1775-1783Campaigns. 3. United StatesHistoryRevolution, 1775-1783Causes. I. Title.

E209.H36 1999 | 98-47260 |

973'3.dc21 | CIP |

Digital Edition FEBRUARY 2022 ISBN: 978-0-06-309297-6

Version 03042021

Print Edition ISBN: 978-0-38-079605-2

For Marion

By the rude bridge

that arched the flood,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

Their flag to Aprils breeze unfurled,

And fired...

... the shot heard round the world.

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

Contents

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Franklin Collection, Yale University Library for permission to use the engraving of Joseph Galloway and to the Independence National Historic Park for permission to use all other portraits.

The day the American Revolution began was not the same day for everyone.

Historically, it began after dawn on Wednesday, April 19, 1775, in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts. But for the residents of New York City the Revolution began on the following Sunday afternoon, April 23 at four P . M ., when express rider Israel Bissel paced his tired horse into that explosive city, crying the news. Philadelphians learned of it the next day, Monday, April 24. Late at night on April 28, an express rider cantered into Williamsburg, Virginia, and roused sleeping residents, who were themselves on the verge of starting the American Revolution. Weeks later a ship would carry the news to the people of Georgia. And in London, it was not until May 28 that stunned cabinet members hastened out of the city by carriage to bring the news to King George III, who was weekending with his family in the royal palace at Kew.

This narrative, rather than dispassionately analyzing events and causes, follows the path of the news from city to city and country to country, into homes, taverns, farms, parliamentary offices, and palaces, and thereby rediscovers that intense emotional moment when word of Lexington and Concord abruptly tore open the lives of many diverse people.

Each life was changed in significantly different ways. While the news was heard with great dismay by John Harrower, an indentured servant in Fredericksburg, Virginia, who was struggling to bring his wife and children from Scotland, Benedict Arnold saw great personal opportunity in it and dared to reach for fame and glory. While deeply troubled Quakers such as Samuel Wetherill were struck suddenly by the realization that their determined pacifism would be regarded by both sides as betrayal, women such as Abigail Adams saw that any new freedom would be for men alone. And while many Loyalists such as Oliver DeLancey would try to fight back, only to be ruinedtheir great fortunes lost, their magnificent mansions torched, and they themselves permanently exiledleaders at the other end of the political spectrum such as George Washington reacted by also risking all, hazarding everything, including their lives, to ride to Philadelphia and join the Revolution.

By peering into these individual lives one finds that many of the thrice-told tales are not true. The picture of George III as an insane tyrant is hardly accurate. The view of all Englishmen and the Parliament standing behind their king, unified against the damned rebels, does not square with the violent disputes that racked Lords and Commons, drawing rooms and taverns, throughout that country. Paul Revere never shouted The Redcoats are coming, nor was he, as Longfellow reported, the express rider who roused Concord that night. There is even a legitimate question as to which shot should be deemed the shot heard round the worldthe first one fired on the green at Lexington or, Emersons choice, the later one at the North Bridge in Concord.

Nor were our founding fathers the giants of the earth that boosters such as Parson Weems painted. Mixed among men of stature were smugglers, slave owners, street thugs, arsonists, hack politicians, hypocrites, opportunists, self-servers, liars, spies, traitors, double dealers, and cowards. But rather than sullying their accomplishments, these flaws make their deeds even more impressive. For to defy a powerful king, to fight and freeze through an exhausting war, and to write the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, they had to reach far beyond their normal capacities to become true heroes.

History is written not by the historians but by the people who lived it. And here they are, from colonial farmer to kingas varied a group as ever shared the same era, ordinary people made extraordinary by the great tidal wave from Lexington and Concord that swept over them. They were about to live throughand causesome of the most dramatic, absorbing, even improbable, events in all of American and English history.

As you will see, the day the American Revolution began has a particularly modern resonance.

W.H.H.

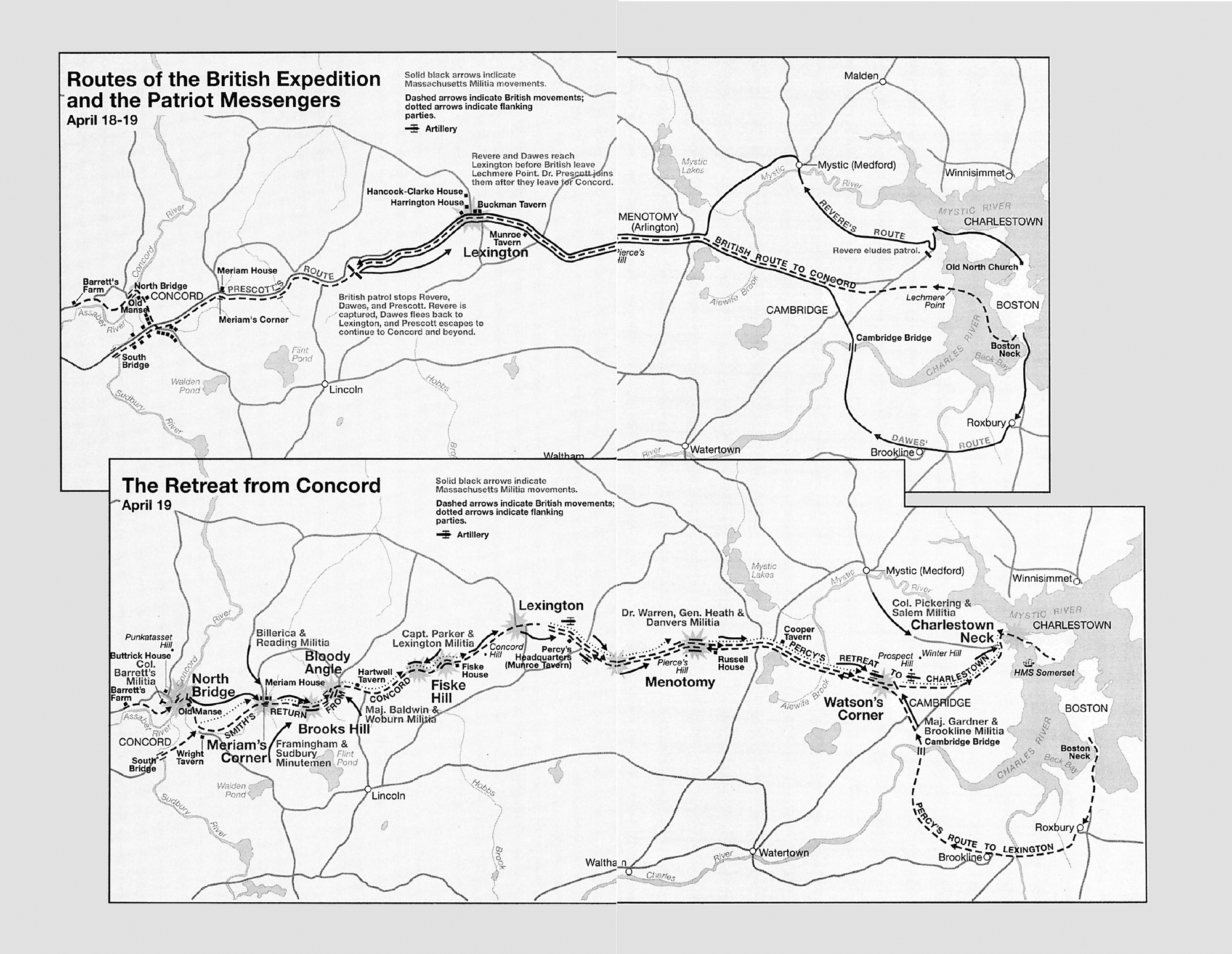

Maps courtesy of the National Park Service.

O n the morning of Tuesday, April 18, 1775, under bright skies and in cool spring temperatures, twenty British officers and sergeants, all mounted, all under the command of the mercurial Major Edward Mitchell of the 5th Foot, rode out of the British army stables in Boston. They traveled down the long thread of land called the Boston Neck, the only land access from the city to the mainland, then, turning north and west, they spread out along the road to Concord.

The preceding winter had been the mildest in New England history. The roads were dry underfoot, and their horses could cover ground quickly. The greenery had begun to grow a month early, and the trees were already budding out.

From their horses, these British soldiers looked at familiar scenes in a peaceful countryside. Farmers were out in their fields, plowing with oxen from first light to the last peep of sun. On the roads, drovers with switches and flailing hats were driving animalseverything from cattle to gabbling flocks of turkeysto Bostons market. Everywhere, people were doing chores and errands in the urgent business of getting crops started. Countless eyes saw Major Mitchell and his mounted military detachment pass by.