WINNING the FIGHT for INDEPENDENCE!

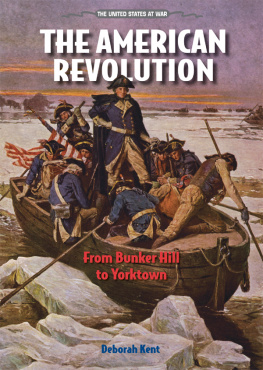

When the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, it marked the birth of a new nation. But the United States of America was not yet free. A brutal war gripped the nation. The grueling fight against Great Britain was far from over. How did the colonies claim victory in the battle for independence? Find out why we won the American Revolution!

An accessible introduction to the battles and personalities of the American Revolution. See how a rabble of American rebels banded together to defeat the mighty British military

Dr. Richard A. Glenn, Professor and Chair of Government and Political Affairs, Millersville University, Pennsylvania

About the Author

Author John Micklos, Jr., is a freelance writer, editor, and visiting author for schools. His many titles for young people include history books, biographies, and poetry books.

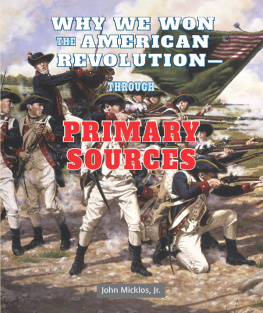

Image Credit: Domenick DAndrea, courtesy of the National Guard

Continental Army troops fire their muskets during the Battle of Long Island.

On the morning of August 22, 1776, five large ships dropped anchor off the southwestern coast of Long Island, New York. The ships all flew the flag of Britains Royal Navy. And they all had big cannons ready to blast the shoreline if necessary. Soon dozens of flatboats filled the narrow waters between Long Island and Staten Island to the west. The boats were crammed with British soldiers. Sailors rowed the boats to a beach at Gravesend Bay. At eight oclock, the soldiers went ashore.

They presented an impressive sight. There were 4,000 men in all. But it did not take long for them to form orderly ranks. The soldiers uniforms included red coats. The polished brass buttons on these coats gleamed in the sunlight. So did the soldiers bayonetslong steel blades attached to the ends of their muskets.

Meanwhile, the flatboats returned to Staten Island to pick up more soldiers. By midday, a massive force of 15,000 men occupied southwestern Long Island. Regimentslarge units made up of hundreds of soldierswere gathered in precise formation on the plain there.

Moving and organizing so many men in such a short time was not easy. It required good officers and well-trained men. The British Army had both. It was perhaps the best army in the world.

The army was a career for most British soldiers, who were known as redcoats. Men who enlisted during peacetime agreed to serve for life. Men recruited during wartime had to serve for three years or until the war was over. The redcoats on Long Island had a lot of military experience. On average, these men had been in the army for nearly six years. The British soldiers were tough and proud. They were confident of their fighting skills.

Image Credit: Valley Forge National Historic Park

The musket and bayonet were essential weapons during the American Revolution. This photo shows two American muskets along with a bayonet.

The British soldiers had little respect for the men they had been sent to Long Island to fight. Unlike the redcoats, these men were not professional soldiers. Most had a year or less of military experience. They were ordinary people from all walks of life: farmers, storekeepers, and tradesmen. However, most important from the British point of view, they were rebels.

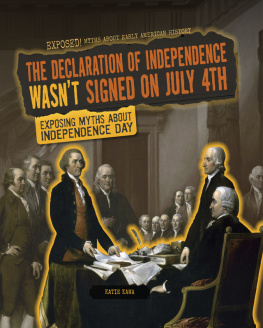

In July 1776, the thirteen American colonies had officially broken away from Britain. Meeting in Philadelphia, representatives of the coloniesthe Continental Congressissued the Declaration of Independence. It listed the ways Britains King George III had violated the colonists rights. It said that the Americans were no longer subjects of the king. They were citizens of the free and independent United States.

By the time the Declaration was issued, the American Revolution had been going on for more than a year. The fighting began on April 19, 1775. That day, a large force of redcoats fought against Massachusetts militia units. The militias were groups of American colonists from the same town or area. They were not full-time soldiers. They were private citizens who trained together and agreed to turn out with their weapons in an emergency. The redcoats had marched out of Boston, where they were headquartered. They planned to seize weapons and supplies the colonists had hidden. At the villages of Lexington and Concord, fighting broke out. Throughout the redcoats long march back to Boston, militiamen shot at them.

Image Credit: National Archives

The Declaration of Independence, signed July 4, 1776, stated the American colonists were no longer subjects of King George III, but free citizens of the United States.

After the battles at Lexington and Concord, about twenty thousand American men flocked to the area around Boston. Many came from Massachusetts. But many were from the other New England colonies. These men took up positions outside Boston. They called themselves the Army of Observation. Really, though, they were more like a collection of militia groups than an army. There was no overall commander. Each colony considered its militia an independent force.

Most British officers thought little of the Americans. One general, John Burgoyne, called them an untrained rabble. They would never be able to stand up to the mighty British army, Burgoyne said. Yet for weeks, the Army of Observation kept British soldiers trapped inside Boston.

On June 17, the British finally came out of the city. In a bloody battle fought on Bunker Hill and nearby Breeds Hill, they found that the rabble would stand up and fight.

Image Credit: Library of Congress Manuscript Division

The Continental Congress needed a capable leader for its new army. This document, signed at the bottom by John Hancock, declared George Washington general and commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.

At the time, there were only about 8,000 redcoats in America. British leaders realized they would need a lot more soldiers to stamp out the rebellion. Regiment after regiment was sent from England to America. King George also hired thousands of German professional soldiers. These soldiers were known as Hessians.

Leaders in the Continental Congress also realized it would take more than militia to fight the British. A regular army was needed. In June 1775, Congress created the Continental Army and appointed George Washington of Virginia as its commander. The new Continental Army would be formed from the so-called Army of Observation outside Boston. Each colony would also raise additional regiments.

In early July, Washington arrived in Massachusetts to take command of the army. He was shocked by what he saw. The troops did not look or act like disciplined soldiers. Drunkenness and brawling were common. Men seemed to wander in and out of camp as they pleased. Also, food and supplies were scarce.

Washington did his best to bring order to his army. But he feared that the British might launch a full-scale attack. He was not sure his men could stop it.