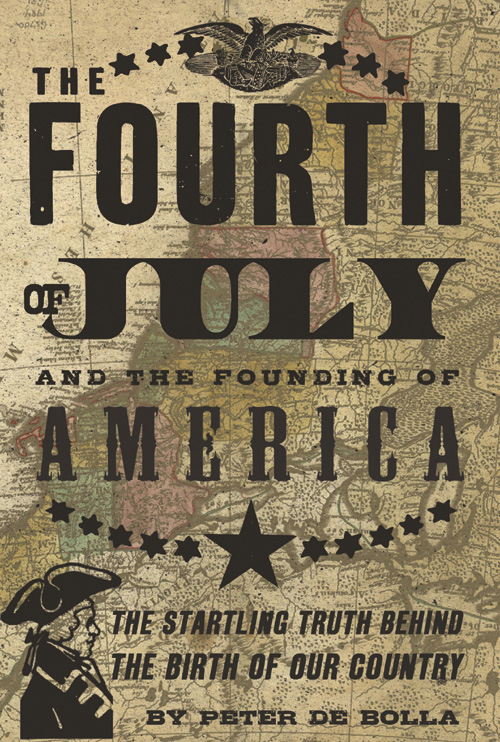

If there is any one thing that has singularly determined the shape and focus for the story of the Fourth of July it is this image. It depicts a moment which in many of the narratives recounting the creation of the United States of America is said to be the originative moment. There are other moments, for sure, which might make a similar claim: the resolution of Congress to adopt the Constitution, for example. But none has been represented in so varied media or contributed so significantly to the iconology of the United States. The painting itself has three versions and it has been reproduced at various times on postage stamps, currency and china, not to mention the hundreds of thousands of prints and photographs which have been taken from it. It is easy to understand why its dissemination has been so extensive since it documents the birthday of the nation. It is a snapshot of what transpired on 4 July 1776. Literally millions of people have seen this version of the painting which hangs in the Rotunda of the Capitol in Washington, DC. It was commissioned by Congress in a vote of 6 February 1817 authorising the fourth president, James Madison, to approach the artist John Trumbull with a request that he create four paintings commemorating the history of American independence. The title of the painting is The Declaration of Independence (for full image, see the endpapers).

Many of the men depicted, life size, seated around the edges of the room are no longer prominent characters in the common knowledge of contemporary Americans, notwithstanding the voluminous literature, both scholarly and popular, on the founding of the nation. Some of them, even in their own lifetimes, were perhaps never particularly well known outside the colony or even town in which they lived. But collectively they are notorious. This is the body of men who comprised the Second Continental Congress: these are the signatories to the Declaration of Independence. Each of them (excepting the man with the hat, the only man wearing a hat, standing in front of the door on the left-hand side), painstakingly rendered in portrait likeness by the artist, assented to the irrevocable step of signalling to the world at large the separation of the colonies from the mother country, thereby instituting the process that was to lead to the creation of the first modern republic: the United States of America. In so far as any snapshot can encapsulate a process this image conveys the signal moment in the story of the Fourth of July.

Although the events of that day in 1776 have been celebrated, for the most part continuously, since 1777, accounts have varied of what precisely did occur in the State House in Philadelphia when these men collectively agreed to the wording of a document that had been drafted primarily by one man, the tall figure in the central group of the painting standing closest to the left side of the desk with a document in his hands, the man who would become the third president of the republic, Thomas Jefferson. Over the course of the following chapters the extent of this variation will become clear. But I shall begin with our own moment in time, with what one might reasonably expect most people today to know about 4 July 1776.

The land mass we now refer to as North America was, in 1776, home to thirteen colonies, all of them independently founded at different times over the previous 169 years and each administered by separate internal institutions. Each was beholden to the British government under the provisions of its own distinct charter and legal instruments which collectively determined that relationship as colonial. By the middle of the eighteenth century those relations had become very strained and by the time of the Stamp Act in 1765, which levied a tax on documents, newspapers and nearly every form of paper used in the colonies, many citizens were beginning to advocate independence from the mother country.

Although each of the colonies administered its own affairs it had become clear by 1765 that acting in concert over the Stamp Act would be advantageous. In October of that year thirty-seven delegates representing each of the colonies met in New York to draw up a plan of action. Ten years later, by the time the Second Continental Congress first met in May 1775, irritation and dissatisfaction with King George IIIs behaviour towards the colonies was running at such a pace that the political will to launch a revolution was in the ascendant. His Majestys attempts to steer a course away from confrontation were less than half-hearted: as far as many of his ministers were concerned the hotheads in the colonies were rebels and needed to be brought back into line by military force. When the shot heard around the world was fired in April 1775 both sides began to be drawn into a confrontation which was unlikely to end amicably. And so by the summer of 1776 independency, as it was referred to at the time, was seen by many as the inevitable next step. This is where the story of the Fourth of July begins.

Of the many and varied events that might be common knowledge about that day in 1776, what appears to be undisputed is that something momentous occurred in the State House in Philadelphia. Here, in words taken from a book entitled The Declaration of Independence by Hal Marcovitz, one of a series for young students called American Symbols and their Meanings, is how that story is told:

[O]n July 4 the Congress intended to vote specifically on the declaration drafted by Jefferson

The delegates entered the Philadelphia State House through the large doorway facing Chestnut Street. Above the door hung the royal coat of arms the final reminder to them that they were still living under the oppressive will of the King of England.

The delegates met in the white-paneled meeting room on the east side of the building. Above, an elaborate crystal chandelier provided candle light. There were two fireplaces in the room and tall windows lining the walls. Displayed in the room were a British drum, swords, and flag captured in 1775 by Continental Army soldiers under the command of Ethan Allan at the battle of Fort Ticonderoga.

The detail of the description gives it a sense of accuracy that helps transport the reader to the physical location, the very room in which the Declaration was made. For many readers it must have an air of familiarity about it since Marcovitz is essentially describing the image millions have seen in the Capitol, the image with which I began. A painting which itself is clothed in the rhetoric of authenticity and historical exactitude: Trumbull, as the evidence of his correspondence and sketches demonstrates, went to extreme pains to produce a documentary image. He travelled across the states tracking down those people who had been present on 4 July 1776 in that room in Philadelphia in order accurately to portray their faces in his painting. Of course, his subjects had advanced in years by the time Trumbull came with pencil, pen or brush in hand he did not begin his studies for the painting in Paris until 1785 and it was not completed until 1818. No wonder so many of them look so august. Similarly the room he positioned them in, with its drum, swords, flags and doorways, is presented to us as an accurate depiction of the Assembly Room in the State House. But when he began his initial sketches of the composition for the painting in the company of Thomas Jefferson in fact it was Jefferson who had suggested the subject for the painting he had never visited Philadelphia. He was, therefore, completely reliant upon the sketch of the room that Jefferson made for him, and as we now know Jefferson had mis remembered many of the details, including the positions of the doorways and the adornments to the walls. Trumbull, in a later version of the same painting, took great care to correct these errors.