Copyright 2008 by William Marvel

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Marvel, William.

Lincolns darkest year : the war in 1862 / William Marvel.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-618-85869-9

1. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Campaigns. 2. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Military leadership. 3. United StatesPolitics and government18611865Decision making. I. Title.

E471.M368 2008

973.7dc22 2007038416

e ISBN 978-0-547-52386-6

v3.0518

For Ellen,

fortissimo e appassionato

List of Illustrations and Maps

All illustrations are courtesy of the Library of Congress.

BEGINNNING PAGE

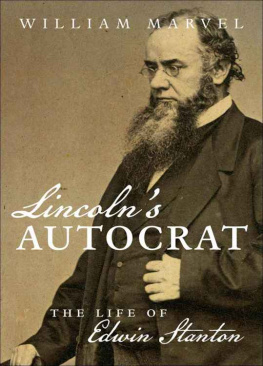

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton greeting his generals

Searching for the wounded after Fort Donelson

Major General Don Carlos Buell

Major General Nathaniel P. Banks

Union remains on the battlefield of Gainess Mill

Field hospital at Savages Station

The retreat from Savages Station

Major General John Pope

Major General Henry W. Halleck

Lincoln and his cabinet

Old Capitol Prison

Union rally in Washington, August 6, 1862

Longstreet surprising Pope at Second Bull Run

Refugees from Sioux uprising in Minnesota

General Braxton Bragg

Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith

BEGINNNING PAGE

Candidates for the Exempt Brigade

Scene, Fifth Avenue

Union troops marching through Middletown, Maryland

Sharpsburgs main street in 1862

Confederate dead in Bloody Lane

Burnsides Bridge

Dead white horse near the edge of the East Woods

Lincoln visiting McClellan in the field

Union troops monitoring the election in Baltimore

McClellans farewell to the army

Ambrose Burnside with his generals

Union troops amid looted property in Fredericksburg

Major General Joseph Hooker

Humphreyss attack on Maryes Heights

Cavalry escorting deserters back to camp

Native Guards on duty in Louisiana

MAPS

All maps by Catherine Schneider

Western Theater ()

Eastern Theater ()

The Seven Days ()

Second Bull Run ()

Antietam ()

Fredericksburg ()

Preface

This is the common story of a war growing completely out of hand and overwhelming the people who started it. As always, opposing factions argued for either peace or continued prosecution, with one group judging the price too great for any potential results and the other reluctant to waste the investment already made. Tragically, victory and peace might have satisfied both parties fairly early, but those opportunities were lost through a closely connected series of blunders, some of which can be traced back to the conscious decisions of Abraham Lincoln. Those executive decisions appear to have been influenced by pressure from Radical Republicans, and in some cases the unfortunate choices contradicted Lincolns own instincts.

The second half of 1861 had seemed laden with Confederate victories over the Union invaders, but 1862 began with a nearly unbroken string of Union triumphs. Most confrontations in the western theater that winter and spring ended in abject Southern defeat, and occasionally in complete surrender. By the end of April, New Mexico had been rid of Southern intruders; New Orleans had fallen; the Southern legions that had defended Kentucky and Tennessee had been driven into the tier of Gulf States, or conducted north as prisoners. The Atlantic coast bristled with Union bases. In May, Federals swarmed into Baton Rougethe second Confederate state capital captured within two monthsand in northern Mississippi a massive Union army closed in on its main opponent, under General Pierre G. T. Beauregard. In Virginia, despite much-criticized delay, George McClellans Army of the Potomac lay at Richmonds eastern approaches with a hundred thousand Union soldiers, and forty thousand more stood at Fredericksburg, ready to swoop down on Richmond from the north and west. The Confederate capital could muster barely half as many defenders as the combined Yankee host, and things looked very gloomy for the new nation of slave states.

Then, in a matter of days, it all fell apart. Beginning on May 23, Stonewall Jackson descended on outnumbered Union defenders in the Shenandoah Valley and sent them flying to the far side of the Potomac River. Abraham Lincoln bore primary responsibility for depleting his Valley divisions and appointing incompetent politicians to command them, and at their flight he fell into a panic, scattering his Fredericksburg troops into the Valley in a needless effort to repel Jacksonand in a vain attempt to capture him. That emasculated the overpowering dual movement against Richmond, where on May 31 Confederates pounced on an isolated wing of the Army of the Potomac and delivered an embarrassing, if uncoordinated, blow. Beauregard slipped his army out of beleaguered Corinth, Mississippi, causing weeks of apprehension that he had reinforced Richmond, and that apprehension posed a serious liability for Union arms at the end of June. Believing himself vastly outnumbered by the Confederates who assailed him so ferociously, McClellan retreated from Richmonds door in a weeklong running fight that left his grand army gasping on the banks of the James River, a good twenty-five miles downstream from the chambers of the Confederate Congress.

In forty days the Union juggernaut appeared to have been halted. The battlefield reverses had all come in Virginia, which carried limited strategic importance in the quest to subdue the South, but the Virginia theater encompassed political symbols that far outweighed its military significance. The embattled hundred miles between Washington and Richmond therefore attracted a disproportionate measure of public attention, and that obsession with events in Virginia cost the Union cause dearly in 1862. The repulse of McClellans promising advance initiated a wave of dejection among the civilian population. The rise of the audacious John Pope, and his bloody disasters at the head of the Army of Virginia that August, had the same depressing effect on Union soldiers. In conjunction with the administrations decision to withdraw McClellan from the James and give most of his army to Pope, Popes failures also brought the war back to the outskirts of Washington, and then into the loyal states.

The restoration of McClellan to field command in September put much heart back in the army. McClellan brought a more deliberate and methodical approach to warfare, which naturally appealed to the men who would have to do the fighting, but McClellans soldiers may have admired him equally for his conservative politics: he advocated reunion uncontaminated by any abolitionist agenda, and that seemed to reflect the opinion of most Union troops in the summer of 1862. His success in repelling the Confederates from Maryland does not, however, seem to have restored Northern confidence so abruptly or so completely as retrospective accounts might suggestas much as it may have dismayed Southern civilians. Their momentary sense of relief aside, many Northern observers gauged the Southern incursions into Maryland and Kentucky that September less as failed invasions than as successful raids that might be repeated any time. It was primarily those who had striven to see the administration adopt a higher ideological purpose than national unity whose spirits brightened in the wake of Antietam, and their optimism arose more from Lincolns decree on emancipation. Those who awaited improvement in the military situation remained doubtful, and the complication of emancipation infuriated those Unionists who had feared all along that abolitionists were scheming to preempt their cause.