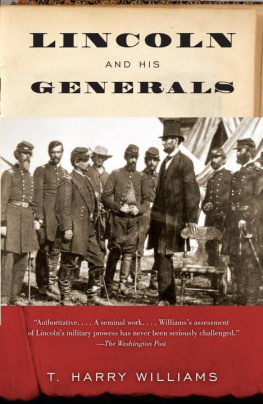

T. Harry Williams

LINCOLN

AND

HIS GENERALS

T. Harry Williams was born in Vinegar Hill, Illinois, in 1909. He taught at the universities of Wisconsin, Omaha, and West Virginia before becoming professor of history at Louisiana State University. Williams was the author of many books on military and political history. The T. Harry Williams Center for Oral History was established at Louisiana State University in 1991.

SELECT WORKS BY T. H ARRY W ILLIAMS

Lincoln and the Radicals (1941)

Lincoln and His Generals (1952)

P.G.T. Beauregard: Napoleon in Gray (1955)

A History of the United States (1959, 2 vols.) with Richard Current and Frank Freidel

Americans at War: The Development of the American Military System (1960)

Romance and Realism in Southern Politics (1961)

McClellan, Sherman, and Grant (1962)

Hayes of the Twenty-third:

The Civil War Volunteer Officer (1965)

Huey Long (1969)

The History of American Wars:

From Colonial Times to World War I (1981)

The Selected Essays of T. Harry Williams (1983)

FIRST VINTAGE CIVIL WAR LIBRARY EDITION, JANUARY 2011

Copyright1952 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.,

copyright renewed 1980 by T. Harry Williams

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1952.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Civil War Library and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Williams, T. Harry (Thomas Harry), 19091979.

Lincoln and his generals / T. Harry Williams.1st edition.

p. cm.

1. Lincoln, Abraham, 1801865Military leadership.

2. GeneralsUnited StatesHistory19th century.

3. United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Campaigns. I. Title.

E470.W78 1952

973.741

51013211

eISBN: 978-0-307-94815-1

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

for tell

tell

Preface

I HAVE WRITTEN in this book the story of Abraham Lincoln the commander in chief. I have not written a military history of the Civil War or a group biography of the principal Union generals or a description of the military organization of the North, although there is something of all of these in the book. My theme is Lincoln as a director of war and his place in the high command and his influence in developing a modern command system for this nation. Always I have tried to describe and evaluate Lincolns acts as a war director from the perspective of military developments since 1865 and to measure the correctness of his decisions by the standards of modern war.

Judged by modern standards, Lincoln stands out as a great war president, probably the greatest in our history, and a great natural strategist, a better one than any of his generals. He was in actuality as well as in title the commander in chief who, by his larger strategy, did more than Grant or any general to win the war for the Union.

Because Lincoln is at the center of the story and because the war is seen only as it unfolded before his eyes, the emphasis or proportion given to certain generals and events may trouble some readers. For instance, John C. Fremont occupies more pages than W. T. Sherman, although Sherman was worth ten Fremonts as a general. The incompetent N. P. Banks gets more space than the able George H. Thomas. Fremont and Banks loom larger than Sherman and Thomas because as commanders they were headaches to Lincoln and hence had intimate command relationships with him. Lincoln saw, militarily, much of Fremont and Banks, relatively little of Sherman and Thomas. Some readers may say that they could do with less of McClellan and more of Grant. So could have Lincoln, but it was his horrible predicament to be saddled with McClellan before he found Grant and to have to supervise nearly everything that McClellan did. Lincoln tried to use McClellan; but rightly distrusting the Generals ability, he intervened frequently in the management of military matters. Rightly trusting in Grants competence, Lincoln intervened less after Grant became general in chief, but even then he always exercised an over-all authority and never hesitated to check Grant when he thought the General was making a mistake. It might be said that before Grant, Lincoln acted as commander in chief and frequently as general in chief and that after Grant, he contented himself with the function of commander in chief. Consequently, as Grant assumed a larger role Lincoln took a smaller onebut he never left the stage entirely.

To the best of my knowledge, this book is the only work that treats of Lincoln as a war directorwith him as the dominating figurefrom the perspective of modern war. It is my hope that my discussion is a contribution both to the history of the American command system and to an understanding of it.

I am under obligation to the following people who gave me aid and comfort in preparing this book: Miss Mai Frances Lower, Dr. Philip D. Uzee, Mrs. George Herlitz, Mrs. Thomas Smylie, Mrs. Helen Bullock, Dr. Horace Merrill, Miss Catherine Heald, Dr. C. P. Powell, Miss Joan Doyle, and the staffs of the Louisiana State University Library and the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress.

For searching criticism and helpful suggestions, I am deeply grateful to Dr. Charles E. Smith of Louisiana State University, a scholar of the Middle Ages who is also a profound and penetrating student of the Civil War.

Contents

Illustrations

Chapter 1

The Pattern of Command

HE Civil War was the first of the modern total wars, and the American democracy was almost totally unready to fight it. The United States had in 1861 almost no army, few good weapons, no officers trained in the higher art of war, and an inadequate and archaic system of command. Armies could be raised and weapons manufactured quickly, but it took time and battles to train generals. And it took time and blunders and bitter experiences to develop a modern command system. Not until 1864 did the generals and the system emerge.

HE Civil War was the first of the modern total wars, and the American democracy was almost totally unready to fight it. The United States had in 1861 almost no army, few good weapons, no officers trained in the higher art of war, and an inadequate and archaic system of command. Armies could be raised and weapons manufactured quickly, but it took time and battles to train generals. And it took time and blunders and bitter experiences to develop a modern command system. Not until 1864 did the generals and the system emerge.

In 1861 the general in chief of the army, which at the beginning of the war numbered about 16,000 men, was Winfield Scott. He was a veteran of two wars and the finest soldier in America. But he had been born in 1786, and he was physically incapable of commanding an army in the field. He could not ride, he could not walk more than a few steps without pain, and he had dropsy and vertigo. The largest single army that most of the younger officers had ever seen was Scotts force of 14,000 in the Mexican War.

There was not an officer in the first year of the war who was capable of efficiently administering and fighting a large army. Even Scott, had he been younger and stronger, would have had difficulty commanding any one of the big armies called into being by the government. All his experience had been with small forces, and he might not have been able to have adjusted his thinking to the organization of mass armies. The young officers who would be called to lead the new hosts lacked even his experience. Not only had they never handled troops in numbers, but they knew almost nothing about the history and theory of war or of strategy. They did not know the higher art of war, because there was no school in the country that taught it. West Point, which had educated the great majority of the officers, crammed its students full of knowledge of engineering, fortifications, and mathematics. Only a minor part of its curriculum was devoted to strategy, and its graduates learned little about how to lead and fight troops in the field. They were equally innocent of any knowledge of staff work: the administrative problems of operating an army or the formulation of war plans. Most of them never learned anything of it in the army, except for those few who They spent most of their army careers fighting Indians or building forts, and there was not much of a staff organization in America for them to get any experience with.

tell

tell HE Civil War was the first of the modern total wars, and the American democracy was almost totally unready to fight it. The United States had in 1861 almost no army, few good weapons, no officers trained in the higher art of war, and an inadequate and archaic system of command. Armies could be raised and weapons manufactured quickly, but it took time and battles to train generals. And it took time and blunders and bitter experiences to develop a modern command system. Not until 1864 did the generals and the system emerge.

HE Civil War was the first of the modern total wars, and the American democracy was almost totally unready to fight it. The United States had in 1861 almost no army, few good weapons, no officers trained in the higher art of war, and an inadequate and archaic system of command. Armies could be raised and weapons manufactured quickly, but it took time and battles to train generals. And it took time and blunders and bitter experiences to develop a modern command system. Not until 1864 did the generals and the system emerge.