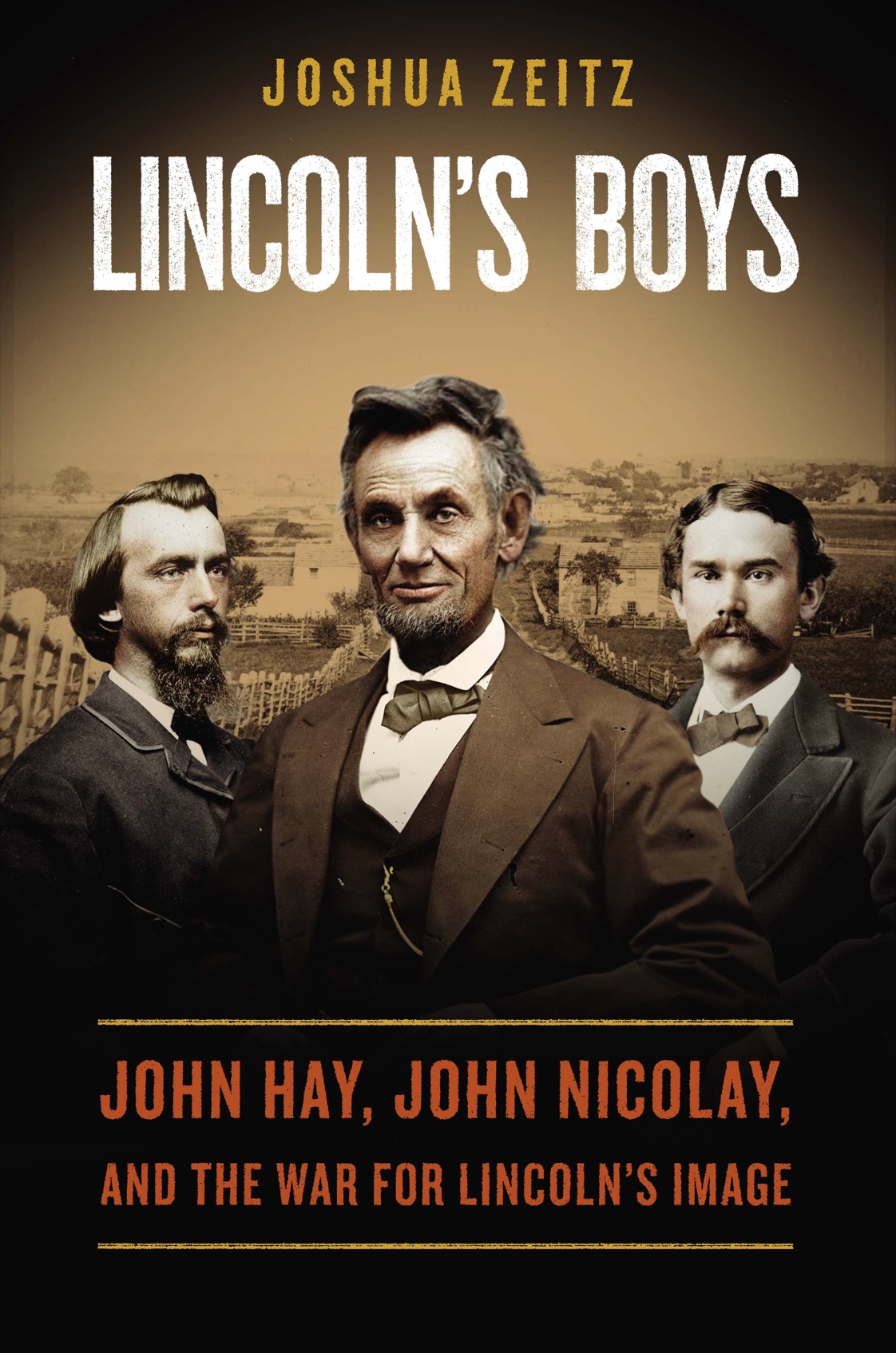

ALSO BY JOSHUA ZEITZ

Flapper: A Madcap Story of Sex, Style, Celebrity, and the Women Who Made America Modern

White Ethnic New York: Jews, Catholics, and the Shaping of Postwar Politics

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright 2014 by Joshua Zeitz

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

A portion of Chapter 15 appeared in different form as Rebel Redemption Redux in Dissent, Winter 2000.

PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS : : John Hay Library, Brown University

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Zeitz, Joshua.

Lincolns boys : John Hay, John Nicolay, and the war for Lincolns image / Joshua Zeitz.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-63807-1

1. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Friends and associates. 2. Hay, John, 18381905. 3. Nicolay, John G. (John George), 18321901. 4. Private secretariesUnited StatesBiography. 5. PresidentsUnited StatesStaffBiography. 6. Lincoln, Abraham, 18091865Influence. 7. PresidentsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

E457.2.Z45 2013

973.7092'2dc23 2013017052

Version_1

For Angela, Lily, and Naomi

Contents

PART IV

Prologue

June 13, 1905

L ess than three weeks before his death, John Milton Hay awoke in his cabin room on the RMS Baltic as the great ocean liner, still the jewel of the White Star Line, steamed a course from Liverpool to New York. He reached for his diary and composed one of its final entries.

It was June 1905. Electric lights and streetcars lined hundreds of American towns. Phonographs and telephones were quickly becoming common fixtures in middle-class living rooms, and for a nickel city folk could gaze into large wood and steel boxes and marvel at moving picture images of prizefighters, ballplayers, and ballerinas. John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie represented the extremes of American wealth and power. It had already been two years since the Wright brothers conducted the first manned test flight of an airplane. In Germany, the theoretical physicist Albert Einstein had recently published a paper on the photoelectric effect and was fast at work developing his theory of relativity. In Vienna, Sigmund Freud published his pathbreaking volume Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality.

In his youth, John Hay could scarcely have imagined this world. A child of the western prairie, he was raised in the age of iron and grew to manhood in the age of steel. A noted poet and historian, former newspaper editor and railroad executive, Hay had served as U.S. ambassador to Britain and, since 1898, secretary of statefirst under President William McKinley and then, after 1901, under President Theodore Roosevelt. He was one of the most powerful men in the world. But his bright spirit was fast burning out a frail body. In his final weeks, his mind wandered back to the simpler world of his youth.

I dreamed last night that I was in Washington, Hay confided to his diary, and that I went to the White House to report to the President, who turned out to be Mr. Lincoln. He was very kind and considerate, and sympathetic about my illness. He gave me two unimportant letters to answer. I was pleased that this slight order was within my power to obey. I was not in the least surprised at Lincolns presence in the White House. But the whole impression of the dream was one of overpowering melancholy.

This is the story of John Hay and John Nicolay, prairie boys who met in 1851 and forged a close friendship that endured over a half century. Fortune placed them in the right place (Springfield, Illinois) at the right time (1860) and offered them a front-row seat to one of the most tumultuous political and military upheavals in American history, then or since.

As Abraham Lincolns private secretaries, they became, both literally and figuratively, closer to the president than anyone outside his immediate family. Still young men in their twenties, they lived and worked on the second floor of the White House, performing the roles and functions of a modern-day chief of staff, press secretary, political director, and presidential body man. Above all, they guarded the last door which opens into the awful presence of the commander in chief, in the words of Noah Brooks, a journalist and one of many Washington insiders who coveted their jobs, resented their influence, and thought them a little too big for their britches (a fault for which it seems to me either Nature or our tailors are to blame, Hay once quipped). These... Secretaries are young men, Brooks grumbled, and the least said of them the better, perhaps.

In demeanor and temperament, they could not have been more different. Short-tempered and dyspeptic, Nicolay cut a brooding figure to those seeking the presidents time or favor. William Stoddard, an assistant secretary under their supervision, later remarked that Nicolay was decidedly German in his manner of telling men what he thought of them... People who do not like himbecause they cannot use him, perhapssay he is sour and crusty, and it is a grand good thing, then, that he is.

Hay cultivated a softer image. He was, in the words of his contemporaries, a comely young man with peach-blossom face, very wittyboyish in his manner, yet deep enoughbubbling over with some brilliant speech. An instant fixture in Washington social circles, fast friend of Robert Todd Lincolns, and favorite among Republican congressmen who haunted the White House halls, he projected a youthful dash that balanced out Nicolays more grim bearing.

Hay and Nicolay were party to the presidents greatest official acts and most private moments. They were in the room when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and they were by his side at Gettysburg, when he first spoke to the nation of a new birth of freedom. When he could not sleep, which, as the war progressed, was often, Lincoln walked down the corridor to their private quarters and passed the time reciting Shakespeare or mulling over the days political and military developments. When his son Willie passed away in 1862, the first person to whom Lincoln turned was John Nicolay. When the president drew his last breath in April 1865, John Hay was by his bedside.

For the rest of their lives, even as they built their own families and careers, Hay and Nicolay inspired a certain measure of wonder and awe. The greater Lincoln grew in death, the greater they grew for having known him so well, and so intimately, in life. Everyone wanted to know them, if only to ask what it had been likewhat he had been like. It was a tough question to answer. Abraham Lincoln worked hard at being inscrutable. The tones, the gestures, the kindling eye, and the mirth-provoking look defy the reporters skill, wrote Brooks. William Herndon, Lincolns law partner, could fairly claim to have known him as well as any man during the Springfield days. But to Herndon, the future president was the most shut-mouthed man who ever lived. He always told only enough of his plans and purpose to induce the belief that he had communicated all, observed another friend, yet he reserved enough to have communicated nothing. Even Lincoln acknowledged as much. I am rather inclined to silence, he admitted, and whether that be wise or not, it is at least more unusual now-a-days to find a man who can hold his tongue than to find one who cannot.