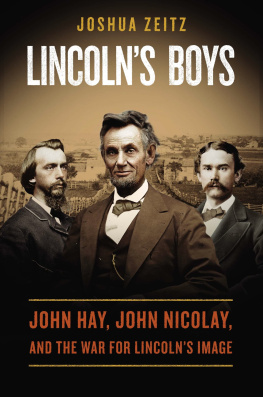

A s the train pulled out of Springfields Great Western Depot on the rainy morning of February 11, 1861, with president-elect Abraham Lincoln and his entourage bound for Washington, D.C., there were three young men aboard with exceptional promise: John Milton Hay, John George Nicolay, and Elmer Ephraim Ellsworth. Of the three friends, two would become the presidents private secretaries during the most tempestuous era the nation had ever known; the third, Ellsworth, would briefly serve as the president-elects head of security.

The twenty-three-year-old Ellsworth, an aspiring soldier, was so short that had it not been for his neat black mustache and whiskered underlip he might have been mistaken for one of the Lincolns little boys. Though he was scarcely five feet in height, what Ellsworth lacked in stature he more than made up for in dignity and authority, having made himself famousa public emblemby a means altogether unique.

The son of a bankrupt tailor in the New York village of Malta, too poor and obscure to attend West Point, Ellsworth, through self-education and exercise, had made himself a drillmaster without peer in America. A born leader, in the late 1850s he organized companies of militia in Chicago that he outfitted in the loose scarlet trousers, blue jackets with gold braid, and jaunty red caps of the French Foreign Legion, calling them Zouaves after the soldiers who fought in the Crimean War. The men paid for their own uniforms. He trained them to do intricate military drills and manuals of arms. He lectured them on patriotism. On parade grounds in the major cities, Ellsworth and his Zouaves drew crowds and newsmen who raved about the little colonel and his superbly trained militiamen. They were equally impressed with Ellsworths temperance, austerity, and code of honor. He refused to accept any pay for his services to his country, past or future.

Like many prodigies and early ripe composers and artists, Ellsworth was not long for this world. The nation was on the brink of war, folks sensed it, and Ellsworth was an avatar of courage and honor. He is a part of the history, essential to getting it under way, and also a victim of it, the first of many lives sacrificed to a cause at first only dimly understood. Lincoln met him during the winter of 185960 when Ellsworth came to study law in Springfield. After watching the Chicago Zouaves drill in a Springfield meadow in August 1860, the presidential candidate invited Ellsworth to remain in town and study law with him. Impressed with the soldiers zeal and intelligence, Lincoln sent him out, with John Hay, to stump for him in the election. He had served the candidate so well that when Lincoln was elected, in November, he invited Ellsworth to attend him as a bodyguard on the train to Washington, with a further prospect of getting him a position in the war department.

TRAVELING ON THE TRAIN with Ellsworth was twenty-two-year-old John Hay. Hay was a poet, a smooth-faced, handsome fellow with a strong chin, long upper lip, and slightly protruding elfin ears that his wavy brown hair partly concealed. His dark eyes were deep-set, liquid, and his friends used to say you could see a mile into them. Only four inches taller than Ellsworth, Hay saw from his vantage point the soldiers form, though slight,exactly the Napoleonic size,was very compact and commanding; Ellsworths sunny smile and deep, musical voice instantly attracted attention; and his address... was sincere and courteous. Hay might as well have been describing his own winning smile and manner; it was not military skill or poetry that had won John Milton Hay his seat on the train to the capitalit was his eloquence and charm.

Hay also owed his place in Lincolns retinue to the insistence of his best friend, the twenty-nine-year-old journalist John Nicolay. Standing next to the poet Hay and the soldier Ellsworth in the trains saloon car, Nicolay, at five feet ten inches and 120 pounds, looked like a gaunt giant, older than his years, with his receding hairline and dark goatee. He had served as Mr. Lincolns personal secretaryat a salary of $75 per monthsince June 7, 1860, soon after the Republicans nominated the rail-splitter to be their standard-bearer. He was Lincolns doorkeeper, his amanuensis, and his confidant. Born in Bavaria, the secretary had a low voice that still showed traces of a German accent. Orphaned at age fourteen and thrown upon his own resourcesa vigorous mind in a frail bodythe former printers devil and editor had never wanted anything so much in his life as to serve the Republican nominee. Lincoln must have sensed this and, knowing Nicolays politics as well as his past, knew he could count on the young mans loyalty and complete discretion.

Shortly after the election, on November 11, 1860, Nicolay wrote to his fiance, Therena Bates, still living in Pittsfield, Illinois, where they had met as children.

I can myself hardly realize that after having fought this slavery question for six years past and suffered so many defeats, I am at last rejoicing in a triumph which two years ago we hardly dared dream about. I remember very distinctly, how in 1854, soon after I had bought the Free Press Office [in Pittsfield], I went to Perry, with others, and heard Mr. Atkinson (the preacher) make the first anti-Nebraska speech which was made in Pike County in that campaign. Though I was fighting as something more than a private then, I should have thought it a wild dream to imagine that in six years after I should find the victory so near the Commander in Chief.

It was Nebraska, the bitter conflict over Stephen Douglass Kansas-Nebraska Actwhich repealed the Missouri Compromise and opened the new territories to the extension of slaverythat brought Nicolay and Lincoln together. Nicolay, as a crusading editor of the free press, and Lincoln, as an ambitious politician, denounced Douglass idea of popular sovereignty, the very idea that settlers in the territories might choose to allow slavery if they pleased.

On October 27, 1856, Lincoln had showed up at a free-soil meeting in Pittsfield. Nicolay, as a member of the Republican committee there that invited speakers, had hoped that Senator Lyman Trumbull, a Democrat, or the Honorable Abraham Lincoln would attend. He could hardly believe his good fortune when he watched, from a crowded shop, as the Democrat Trumbull welcomed the newly arrived Republican, Lincoln, and the two politicians warmly embraced on the street. Men of conflicting parties, they were united by the cause of freedom. Somewhat later in the day, Lincoln ran into a friend, the educator John Shastid, and asked him where he might find an honest printer. Shastid led Mr. Lincoln to the east side of the square, where he found John Nicolay in the offices of the Free Press.

Charmed by the kindly smile, the earnest eyes, the hearty grip of the forty-seven-year-old lawyer, Nicolay was eager to hear Lincolns speech that evening. And he reported the enormous success and turnout at the free-soil rally, at least twice as large as the late [Stephen] Douglas demonstration. from then on, he would never neglect an opportunity to write about Lincolns progress. As Nicolay recalled years later, the orator held him spellbound and cemented his devotion.

And Lincolnfor his partwas impressed with the idealistic journalist. Nicolay was growing restless in the village. In July of 1857, Lincoln helped raise $500 to subsidize Nicolay as an agent for the MissouriDemocrat, a staunchly free-soil newspaper published in St. Louis, with orders for him to increase the newspapers circulation in Illinois. Preferring journalism to sales, Nicolay wrote more columns than the paper desired while selling too few subscriptions. The financial panic of 1857, touched off by the failure of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company, discouraged all business ventures, publishing included. By the end of the year, the publishers relieved him of his duties. He returned, wistfully, to Pittsfield.