THE SECOND DAY AT GETTYSBURG

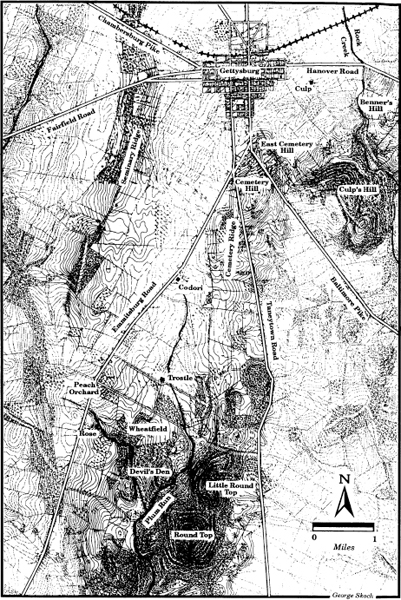

Battlefield of the Second Day at Gettysburg

THE SECOND DAY AT

GETTYSBURG

Essays on Confederate and Union

Leadership

edited by

GARY W. GALLAGHER

The Kent State University Press

KENT, OHIO, AND LONDON, ENGLAND

1993 by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio 44242

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 93-16146

ISBN 0-87338-481-4

ISBN 0-87338-482-2 (pbk.)

Manufactured in the United States of America

03 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 6 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Second day at Gettysburg : essays on Confederate and Union

leadership / edited by Cary W. Gallagher.

p. cm.

Continues: The First day at Gettysburg / edited by Gary W.

Gallagher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-87338-481-4 (cloth : alk. paper), ISBN 0-87338-482-2

(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Gettysburg (Pa.), Battle of, 1863. 2. Command of troopsCase studies. I. Gallagher, Gary W. II. First day at Gettysburg.

E 475.53. S 46 1993

973 7349dc20 93-16146

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available.

Contents

If the Enemy Is There, We Must Attack Him:

R. E. Lee and the Second Day at Gettysburg

The Peach Orchard Revisited:

Daniel E. Sickles and the Third Corps on July 2, 1863

If LongstreetSays So, It Is Most Likely Not True:

James Longstreet and the Second Day at Gettysburg

A Step All-Important and Essential to Victory:

Henry W. Slocum and the Twelfth Corps on July 12, 1863

No Troops on the Field Had Done Better:

John C. Caldwells Division in the Wheatfield, July 2, 1863

T he essays in this book continue the evaluation of selected commanders during the Gettysburg campaign begun in The First Day at Gettysburg: Essays on Confederate and Union Leadership . The focus shifts to the second day of battle, which encompassed the famous struggles for Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, and the Peach Orchard, as well as the less well-known fighting along the slopes of Culps Hill. The first day had progressed from a meeting engagement into a bitter contest between significant elements of both the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac, ending with triumphant Confederates driving Union defenders onto high ground south and southeast of Gettysburg. With the bulk of both forces present on July 2, R. E. Lee resumed the tactical offensive begun the previous day. These assaults by an army at the peak of its power and confidence matched in spirit and persistence any mounted previously by Lees men and nearly gained success against each flank of the Northern line. Facing a series of crises highlighted by the spectacular disintegration of Daniel E. Sickless Third Corps, George G. Meades army repeatedly flirted with disaster before holding on in the end.

Events on July 2 ignited controversies relating to Confederate and Union generalship that have persisted for 130 years. On the Confederate side, a host of Lost Cause writers savaged James Longstreet for failing to launch his attack earlier in the day. Seeking to remove any taint of defeat from Lee as well as to wound Longstreet, whose Republican politics and willingness to criticize his old chief made him an easy target, prominent former Confederates such as Jubal A. Early, Fitzhugh Lee, and John B. Gordon claimed that Lee had ordered his senior lieutenant to open the battle at dawn. They insisted that if Longstreet had struck the Union left in the morningor even earlier in the afternoonSouthern infantry would have taken Little Round Top and rendered untenable the entire Union line. Assailed in print for several decades, Longstreet responded with accounts of the battle marked by errors, dissembling, and rancor. Many historians of the twentieth century, most notably Douglas Southall Freeman in his immensely influential biography of Lee, essentially repeated the arguments articulated by Longstreets tormentors. Other scholars rallied to Old Petes defense, among them Glenn Tucker, whose books on Gettysburg reached a wide audience, and William Garrett Piston, who turned a judicious eye toward the postwar controversies in his study of Longstreet.

The debate over Longstreets role on July 2 inevitably involves an assessment of Lees generalship in the wake of the first days victory. The Confederate commanders decision to press for complete victory via a renewed offensive received the approbation of most Lost Cause writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; similarly, Freeman suggested that Lee, far from home and facing an uncertain logistical situation, had no viable alternative. In contrast, Edward Porter Alexander, commander of Longstreets guns in the action on July 2, vigorously argued that the Army of Northern Virginia should have taken up a good line and forced Meade to attack. Many modern historians agree with Alexanders opinion that Lee might easily have switched to the defensive and awaited an opportunity to deliver a decisive counterpunch.

The most acrimonious disagreement about Federal generalship on July 2 has centered on Daniel E. Sickless decision to occupy an advanced position embracing the high ground at the Peach Orchard. As with the controversy that raged over Longstreets behavior, nineteenth-century arguments about Sickles included heavy doses of politics and special pleading. Anyone seeking to reach dispassionate conclusions about this aspect of the battle must use accounts by participants with great care.

The contributors to this book address a number of topics relating to command on the second day at Gettysburg. The first essay examines key questions concerning Lees decision to order a new round of assaults. Did he have better options? Did he give free rein to his naturally aggressive personality? And is it fair to look at Gettysburg in isolation, or should Lees decision be judged in the context of the history of the Army of Northern Virginia? William Glenn Robertson then reviews the case against Dan Sickles, taking into account the importance of reputation and clashes of personality as well as military factors such as the nature of the terrain and perceptions about the tactical situation. In the third essay, Robert K. Krick draws on wartime testimony unstained by Lost Cause propaganda to reassess Longstreets actions. Finding a consistent pattern in Longstreets behavior throughout the war, Krick reaches conclusions that are certain to provoke further debate.

The last two essays depart from such hotly contested historiographical ground. A. Wilson Greene looks at Henry W. Slocum and the Union Twelfth Corps. The senior Union corps leader, Slocum has received scant attention in the mammoth literature on Gettysburg. Greene offers a convincing portrait of a general unwilling or unable to act decisively and a corps that fell far short of achieving its full potential at Gettysburg. In the final essay, D. Scott Hartwig shifts the spotlight to the divisional level, where he reconstructs the chaotic experience of directing large numbers of men in mid-nineteenth century combat. Cast as attackers in a Union drama dominated by the tactical defensive, John C. Caldwell and his men performed admirably before factors beyond their control overwhelmed them. Hartwig suggests why good tactical plans often went astrayand why modern students should exercise care in criticizing Civil War commanders for failures on the battlefield.