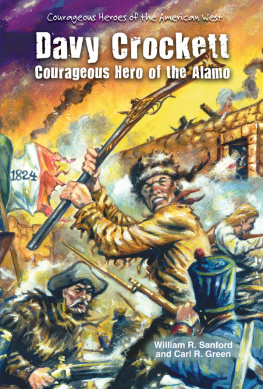

Victory or Death!

Hopelessly outnumbered, Davy Crockett and the defenders of the Alamo rallied around this battle cry. The courageous Texans chose to defend the fort in San Antonio against more than two thousand Mexican soldiers. Fighting for their freedom, the Texans were happy to have the well-known Tennessee backwoodsman, Davy Crockett, on their side. And Crockett gave his life defending freedom. Although his brave deeds at the Alamo made him legendary, Crockett had already gained fame as a hunter, soldier, and U.S. Congressman. Authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green explore the life of this American hero.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

This book tells the true story of Davy Crockett. Davy was one of the American Wests greatest heroes. In his day, he was known as an outstanding hunter, politician, storyteller, and soldier. His daring exploits were recorded in newspapers, magazines, and almanacs of the early 1800s. In more recent years, Davy has been featured in films, books, and a popular television series. You may be amazed to learn that one man could pack so much adventure into a single lifetime. If so, rest easy. All of the events described in this book actually happened.

Dawn came to San Antonio soon after six oclock on March 6, 1836. Inside the Alamo, the old mission turned fortress, weary Texans checked their guns. The men had been under siege for twelve long, bloody days.

Davy Crockett stood on the south wall. A tall man in a coonskin cap, Davy was Americas best-known frontiersman. He was there to help Texas win its independence from Mexico. Freedom, Davy believed, was worth fighting for.

Eight hundred yards away, a red flag flew atop the San Fernando Church. Davy knew what the flag meant. General Antonio Lpez de Santa Anna, Mexicos dictator, had vowed to take no prisoners. Victory, it seemed, lay within his grasp. The Texans were outnumbered, 2,400 to 183.

Colonel William Travis commanded the Alamo. On February 24, he had called on Texans to come to his aid. Thirty-two fighting men from Gonzales had slipped into the Alamo on March 1. No further help had come. James Fannin had four hundred men under arms at Goliad, but he was reluctant to risk the long march to San Antonio.

Commander-in-chief Sam Houston had long ago given the Alamo up for lost. In January, he had ordered Colonel Travis to blow up the fortress. Travis refused the order. He had prepared his men to fight to the end. His only course, he said, was Victory or death!

Santa Annas troops advanced to the sound of bugles blowing the deguello. Like the red flag, the stirring music warned, We take no prisoners.

A hail of rifle and cannon fire poured down on the attackers. Davy fired his long-barreled rifle with deadly accuracy. The enemys muskets could not match Old Betsys three-hundred-yard range. The first wave slowed and fell back. Santa Anna rallied his men, and they returned to the attack. Texans were dying, too. The survivors kept up a steady fire and managed to beat back the second assault.

Urged on by their relentless officers, the assault troops carried their ladders forward a third time. Scores of Mexican soldiers died, but many reached the walls. Waves of soldiers in blue and white uniforms poured into the fortress. With no time to reload, Texans swung their rifles like clubs. The Mexicans pressed forward behind blood-stained bayonets.

Davy and a handful of Texans made a last stand in the barracks. They fought behind a wall of mattresses, chairs, and tables. One by one, the defenders fell, dead or wounded. Mexican reports of the battle told what happened next. Their shot bags empty, Davy and a few survivors laid down their arms. General Manuel Castrillon stepped forward. He pledged that the prisoners would not be harmed.

Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

In this painting, the outnumbered Texan defenders fire their weapons at the attacking soldiers inside the Alamo after the Mexicans had breached the forts walls.

The sight of the prisoners sent Santa Anna into a rage. He tongue-lashed Castrillon for breaking his no prisoners order. Enrique de la Pea, one of Santa Annas officers, caught sight of Davy Crockett. Santa Anna, de la Pea wrote, ordered [Crocketts] execution. Several officers thrust themselves forward and with swords in hand, fell upon these defenseless men just as a tiger leaps upon his prey.

Image Credit: Superstock / Everett Collection

Davy Crockett (center) raises Old Betsy as the Alamos defenders make their last stand. Over the years, many stories of Davys death have been told. The full details may never be known, but there is no doubt that he died fighting for freedom.

The dictators triumph would soon cost him dearly. Six weeks later, Sam Houstons troops engaged the Mexicans at San Jacinto. His fiery troops screamed, Remember the Alamo! as they routed Santa Annas forces. Texas had won its war for independence.

Americans did not want to hear that Davy had died a prisoner. By the end of the month, a story that denied the Mexican report was making the rounds. David Crockett, a writer claimed, was found dead with about twenty of the enemy with him and his rifle was broken to pieces.

In the long run, the details do not matter. What counts is that this great American hero died fighting to free Texas from Mexican rule. Those who knew him were not surprised. From childhood on, Davy Crockett had always been one of a kind.

The Crocketts came to America from Ireland in the 1700s. Around 1776, David Crockett moved from North Carolina to the northeast corner of Tennessee. His son John fought in the Revolutionary War. After the war, John and his wife, Rebecca, started their own farm on Limestone Creek. Along with corn and hogs, the Crocketts raised a fine group of children. On August 17, 1786, their fifth son arrived. Rebecca and John named him David, after his grandfather.

John worked hard, but he never had much luck. In 1794, he built a small mill on Cove Creek. A flood washed the mill away that same year, but John did not quit. He made a fresh start by opening a tavern on the Virginia-Knoxville road. Each night, Davy listened as weary travelers spun tall tales before bedding down. Soon the boy was telling stories of his own. The habit stayed with Davy for the rest of his life.

By 1798, John and Rebecca had six sons and three daughters. Money was scarce. Davy helped feed the family with the game he bagged in the woods. When the boy was twelve, John hired him out to work for Jacob Siler. Davy received $5 for tending Silers cattle during the long journey to his farm in Virginia. When they arrived, Siler pressured Davy to stay with him. Unsure of his rights, the homesick boy agreed. Five weeks later, a friendly teamster helped Davy escape.

Image Credit: Brent Moore / seemidTN.com