Pikes Peak!

After the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory in 1803, the young nation needed brave pioneers to explore this vast uncharted land. Zebulon Pike, a young frontier soldier, welcomed the challenge. Heading southwest from St. Louis, Missouri, Pike led an expedition across rolling prairies before arriving at the towering mountains. Pike became the first American to explore the southern Rocky Mountains. The highest peak in the range, which he never reached himself, now bears his namePikes Peak. Authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green explore the life of this American trailblazer.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

Soaring more than fourteen thousand feet, Pikes Peak dominates the southern end of the Rocky Mountains. The mountain takes its name from the man who first explored this region for the United States. His name was Zebulon Montgomery Pike. Fifty-two years after Pike first sighted the towering peak, a gold rush took place seventy-five miles away at Cherry Creek. Prospectors hurried across the plains with Pikes Peak or Bust painted on their wagons. Few of them knew the full story of the trailblazer who opened the way for them. Zebulon Pikes adventurous 18061807 journey gave Americans their first glimpse of the southwestern segment of the Louisiana Purchase. This book tells the true story of his life.

The date was November 15, 1806. The journey was not going well, but Lieutenant Zebulon Pike pushed on. He had led his small party west from St. Louis five months before. Out on the Great Plains, the weather had turned cold. Their horses found only bark and cottonwood leaves to feed on. One by one, the animals had fallen and died.

That afternoon, a mountain range appeared on the horizon. Zeb pulled out his spyglass. The tallest peak, he wrote later, appeared like a small blue cloud.

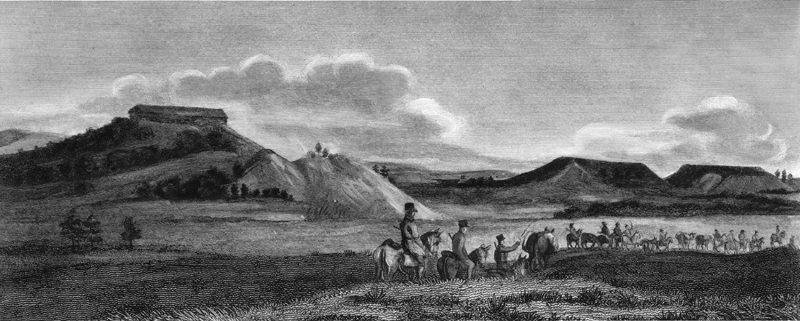

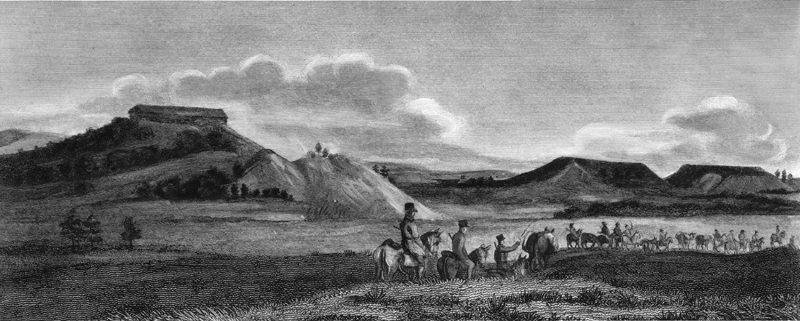

Zebs men briefly forgot their months of hardship. They whooped and cheered joyously at the sight of the Mexican mountains. The explorer marked the range in his notebook. Today, we know he was looking at the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. Zeb guessed that he had found a natural boundary between the Louisiana Territory and New Mexico.

Image Credit: The Granger Collection, NYC

This 1822 engraving shows the broken table lands seen by Zebulon Pike on his expedition west in 1806 as his party approached the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. After months of hardship crossing the barren plains in winter, Zebs small party celebrated the sight of the Mexican mountains.

In the clear air, the highest peak looked quite close. Zeb turned northwest toward what he called the Grand Peak. Twenty-five miles and two days later, however, the mountain looked no closer. A chance meeting with a Pawnee war party added new dangers. Only a quick retreat saved the outnumbered white men from a bloody fight.

On November 24, the men built a small fort next to the Arkansas River. The city of Pueblo, Colorado, now stands on the site. At noon, Zeb led three men toward the Grand Peak. Because the mountain looked so close, the small group traveled light. At sunset, they were still trudging across the prairie. That night, they made a dry camp under a cedar tree.

The next day, the men crossed twenty-two miles of wooded hills. Night found them camped below what looked like the Grand Peak. They drank from a spring and killed two buffalo for supper. Zeb took measurements and added new details to his map.

Looking up, Zeb made a bad guess. He told his men that they could make the climb and return in a day. To lighten their packs, they left blankets and food behind. Steep, slippery rocks soon turned the easy climb into a nightmare. Darkness found the climbers well below the summit. They shivered through a long night in a snow cave.

The next days climb took the climbers through deep snow. Far below, clouds moved across the prairie. Zeb said the clouds looked like the ocean in a storm, with wave piled on wave. An hour later, the men reached the top of the peak. Zeb saw at once that this was not Grand Peak. The massive mountain lay waiting, fifteen miles farther on. It towered twice as high above the plain as Cheyenne Mountain, the peak he was standing on. No human being, Zeb thought, could have ascended to its pinical [sic].

The hungry men took a faster route back to their base camp. There they found that ravens had scattered their food cache. Thanksgiving dinner was a piece of deers rib and a partridge. After some buffalo passed within rifle range the next day, the party ate better. The weary men reached their fort on November 29.

Zeb Pike never did climb the mountain that bears his name. He was not even the first to see Pikes Peak. American Indians and Spanish traders had known about it for two centuries or more. It was Dr. Edwin James who conquered the peak. That was in 1820, just fourteen years after Zeb said it could not be done. By then, mapmakers were using Zebs name on their charts. Deserved or not, the name stuck.

A road to the top of Pikes Peak opened in 1915. Zeb would have been amazed.

In 1775, Americans rose in revolt against Great Britain. As armies clashed, wives kept the home fires burning. One of these resourceful women was Isabella Pike of Lamberton, New Jersey. On January 5, 1779, Isabella gave birth to a son. She named him for his soldier father, Zebulon. Later, the couple gave the boy a middle name, Montgomery. His name paid tribute to a hero of the American Revolution.

Peace returned to the new nation in 1783. Pike left the army and moved his family to eastern Pennsylvania. Bad luck seemed to follow them there. The rocky soil produced poor harvests. Two of the Pikes three boys fell ill with tuberculosis. Only little Zeb and his sister Maria escaped the dreaded disease.

Schooling was hard to come by. Zeb went to country schools from time to time. His parents also taught him at home. Mathematics was one of his strengths. Later, as an adult, he taught himself more math and science. The nearby woods taught other useful lessons. Zeb became a crack shot and a skilled woodsman.

The lure of cheap land drew farmers west. As the frontier advanced, the Shawnee, Delaware, and other Old Northwest Tribes took to the warpath. The call for soldiers led Zebs father to join the state militia. Late in 1791, Captain Pike was serving near what is now Greenville, Ohio. Faced with their first enemy fire, many soldiers broke and ran. Pike staged a fighting retreat that saved a number of lives.

Congress sent the regular army to replace the militia. General Mad Anthony Wayne soon whipped his command into shape. In April 1793, Wayne put Captain Pike in charge of Fort Washington. Pike moved his family to the site on the Ohio River. There, fourteen-year-old Zeb met General James Wilkinson. The meeting helped shape Zebs future.

Wilkinson was a poor role model. Scandals had twice forced him to resign from the army. He was in uniform only because the nation needed well-trained officers. When Zeb first met him, Spanish officials were paying the general to help bring Kentucky under their control. Wilkinson also kept the Spanish supplied with American secrets. Most of those secret plans were fakes that he created himself.