Leading the Way to the West!

Appropriately nicknamed the Pathfinder, John C. Frmont blazed many trails across the Wild West. Frmont carved paths over the Rocky and Sierra Nevada mountains. He led expeditions through uncharted wilderness and provided the first useful maps of California and Oregon. However, Frmont did more than explore. As a soldier, he helped California fight for its independence and served as one of the states first senators. His career as a politician even included a run for president. Authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green reveal the remarkable life of the Pathfinder.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

This book tells the true story of John Charles Frmont. During his lifetime, many people knew him by his nickname: the Pathfinder. He was a courageous and determined explorer and a distinguished army officer. The newspapers of the day ran lengthy reports on his adventurous journeys throughout the West. You may doubt that one man could pack so much adventure and achievement into a single lifetime. If so, rest easy. All of the events described in this book are drawn from firsthand reports.

In 1845, the Congress of the United States voted to annex Texas. That act caused friction with Mexico. Should the Texas-Mexico border be set at the Rio Grande, or at the Nueces River? Fighting broke out the following spring. As the war heated up, some American leaders looked farther west. They dreamed of a land that stretched from sea to shining sea.

Captain John Charles Frmont helped make the dream come true. For years, he had been exploring new routes to the Pacific coast. In early June 1846, he led his mountain men into northern California. His orders were as vague as his purpose was clear. Exploration could wait. California must be free!

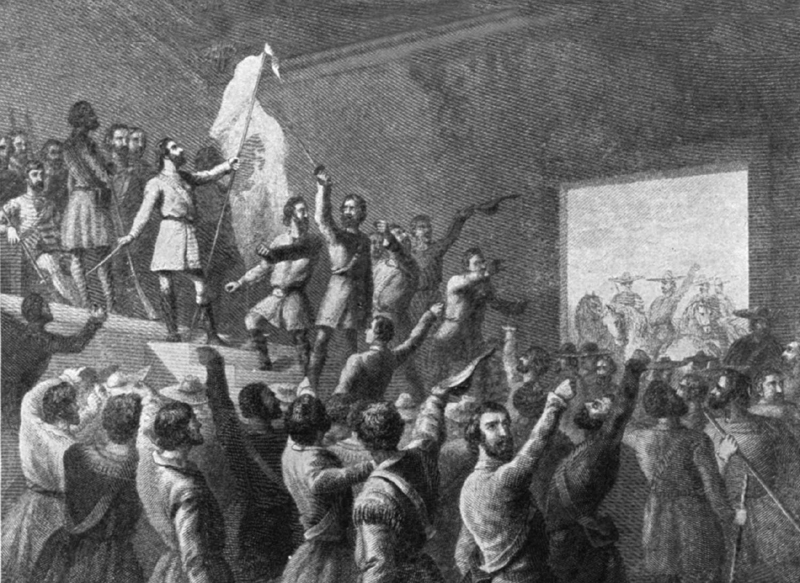

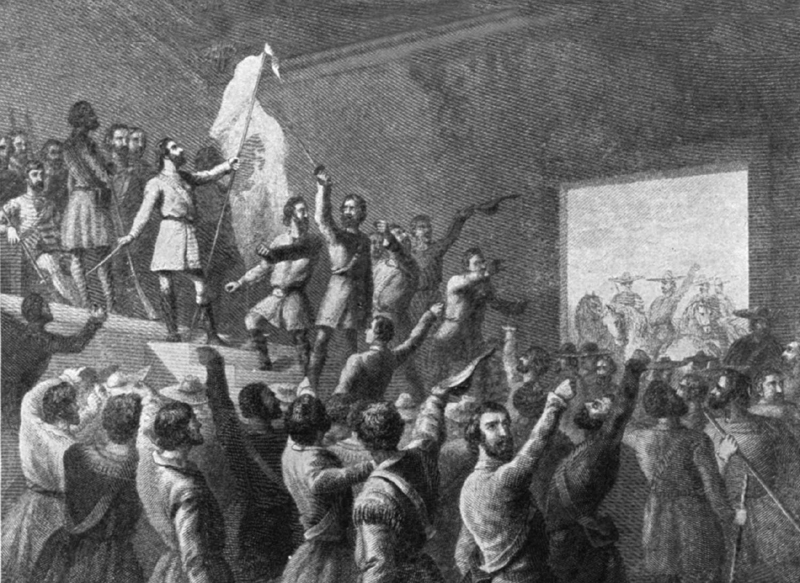

Frmont reached California just as events were reaching a climax. Calling themselves Los Osos (The Bears), the American settlers struck the first blow. Governor Jos Castro was gathering supplies for his army. On June 10, Los Osos stole 150 of his horses. Before Castro could react, they marched on the town of Sonoma. The Mexican defenders gave up after a brief battle. On June 15, a handmade flag rose over the fort. The flag featured a red star and a brown bear above the words California Republic.

Frmont set up a command post at Sutters Fort, near Sacramento. By now, 234 tough, well-armed men had joined him in his quest. When Frmont heard that Castro was planning to retake Sonoma, he marched at once to the settlers aid. Los Osos welcomed Frmont and made him their commander. News that the United States and Mexico were at war reached California on July 2. With war declared, the U.S. Navy could take a hand.

On July 7, Commodore John Sloat sailed into Monterey Bay. A few days later, the Stars and Stripes also flew over Yerba Buena (todays San Francisco). Even there, Frmont had played a role. Some months before, his raiding party had wrecked the guns at Yerba Buenas Fort Point. Frmont also gave the bays beautiful entrance its namethe Golden Gate.

The forceful Commodore Robert Stockton replaced Sloat. One of his first acts was to promote Frmont to lieutenant colonel. With the new rank went command of the Naval Battalion of Mounted Volunteer Horsemen. Frmont, an army officer, obeyed the commodores orders. The country was at war.

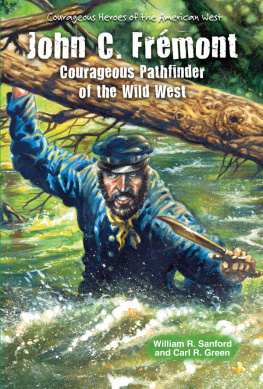

Image Credit: 2011 Clipart.com, a division of Getty Images

John C. Frmont hoists the brown-bear flag as California settlers celebrate their declaration of independence from Mexico. This historic series of events became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

Events moved quickly. On July 17, Frmonts unit captured the San Juan Bautista mission. They found some of Castros supplies hidden there. Two days later, the horsemen rode into San Jose. The next target was San Diego. After a rough sea voyage, the battalion took the city without firing a shot. Castro had fled. When Los Angeles fell, Frmont thought the war in California was over. On August 31, he marched north.

The Americans, however, had overlooked a very stubborn foe. Californias Mexican landowners, the Californios, rose in revolt. The small U.S. force in Los Angeles surrendered to them. In late November, Frmont rode south to face this new threat. Heavy rains slowed his march. On December 27, the battalion limped into Santa Barbara. A few days earlier, Frmont had planned to burn the city. He spared it when the locals promised to end their revolt.

The Californios near Los Angeles were caught in a trap. Frmont was driving south. General Stephen Kearny was marching north from San Diego. The Californios feared Kearny. They knew he would want to avenge his defeat at San Pascual. On balance, it seemed better to surrender to Frmont. On January 13, their leaders met Frmont at Cahuenga Pass.

The Californios agreed to lay down their arms. In return, Frmont promised that the United States would respect their lives and property. The next day, he rode into Los Angeles at the head of his soldiers. The mud-smeared men marched proudly behind their colonel. The soldier-explorers South Carolina childhood must have seemed long ago and far away.

John Charles Frmont had his first brush with death in 1814. The one-year-old was sleeping in a Nashville hotel room. Out in the hallway, two men started shooting. A stray bullet smashed through the wall. The slug missed the baby by just inches. A moment later, the duel was over. Andrew Jackson, the future president, lay wounded. The victor was Thomas Hart Benton. In a twist of fate, the grown-up Frmont later married one of Bentons daughters.

The events that led to that close call began in 1808. That was the year Charles Frmon turned up in Richmond, Virginia. The handsome newcomer claimed to be a fugitive from the French Revolution. He found work in Richmond as a teacher and painter. In 1810, Major John Pryor hired Frmon to teach French to his young wife, Anne.

The major was old enough to be Annes grandfather. The loveless marriage had been arranged by Annes family. Now she found comfort in Frmons arms. In 1811, an outraged Pryor learned of the affair. He threatened to kill her. A day later, Anne and Frmon ran off. In those days, divorce was rare. Anne could live with Frmon, but she could not marry him.

The happy couple traveled widely. When their money ran out, they settled in Savannah, Georgia. Frmon taught dancing. Anne ran a boardinghouse. She gave birth to John Charles there. The most likely date was January 21, 1813. Anne later gave birth to a girl and a second son. Both died young.

Frmons death in 1818 left Anne with a five-year-old child to support. Aided by friends, she settled in Charleston, South Carolina. The guests at her new boardinghouse knew her as Anne Frmont. Adding the t made the name seem more American.

At age thirteen, young Frmont caught the eye of lawyer John Mitchell, who hired the boy as a clerk. When asked to survey a rice field, he impressed his boss with his skill and neatness. With the kindly lawyer paying the bills, Frmont enrolled at prep school. Within a year, he was reading Latin and Greek. In his spare time, he studied maps of the night skies.

In 1829, Frmont earned a scholarship to the College of Charleston. The sixteen-year-old was a clever student but a careless one. On sunny days, he cut class to explore Charlestons meadows and marshes. A schoolboy romance cost him more study time. Early in 1831, the college lost patience. With graduation only weeks away, Frmont was dismissed.