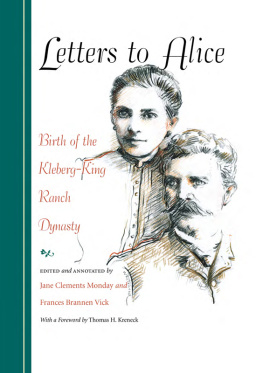

The Cattle King!

In the broiling heat of Texas, Richard King built an empire. Before he arrived in Texas, cattle ranching barely existed in the United States. Although it was a hostile land of sand and brush, King saw an opportunity in the Lone Star State. With great skill and tireless determination, Captain King developed a thriving industry, bringing beef to the northern states and inventing modern ranching. Authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green explore the life of el Patron, the Boss, from his humble beginnings to his creation of a cattle empire: the King Ranch.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

Richard King was a penniless steamboat pilot when he first came to Texas. After the Mexican War, he purchased a boat and went into business for himself. A few years later, he threw himself into the task of building a successful ranch. The obstacles were many. King had to carve his ranch from a hostile land of sand, brush, and broiling heat. As if nature were not challenge enough, he also had to fight off outlaws and find markets for his cattle. With skill, perseverance, and courage, he built a cattle empire that still endures. This is his true story.

Texas has always inspired grand dreams. In the late 1860s, Captain Richard King was one of the dreamers. The Civil War was over, and there were fortunes to be made in the Lone Star State. Although the steamboat pilot turned rancher owned thousands of acres, he longed for more. Someday, he vowed, he would own all of South Texas from the Nueces River to the Rio Grande.

Thousands of longhorns grazed on Richards Santa Gertrudis Ranch. If he found a market for those fast-growing steers, he could buy more land. His chance came with the rising demand for beef in the northern states. A steer worth $11 in Texas sold for $32 in Chicago. The problem was one of transport. Shipping cattle by boat was too costly. The railroad was cheaper, but the nearest railhead lay far to the north. Richard would have to drive his longhorns overland.

The numbers were daunting. A thousand miles of prairie lay between the ranch and the Kansas railheads. Moving at a top speed of twelve miles a day, a cattle drive would take at least three months. If the cattle lost weight, their price dropped. Richard had to plan his drives for months when the grass was good.

Richard sent his vaqueros (cowboys) north to Abilene, Kansas, with a herd in 1870. Dozens of trail drives soon followed. A cowboy wrote in 1882: On reaching Santa Gertrudis ranch, [we] learned that three trail herds, of over three thousand head each had already started. Four more were ready to follow. During the next fifteen years, Richard sent more than a hundred thousand steers up the trail. Most were destined for the Midwestern slaughterhouses. Others stocked new ranches in Wyoming and Montana.

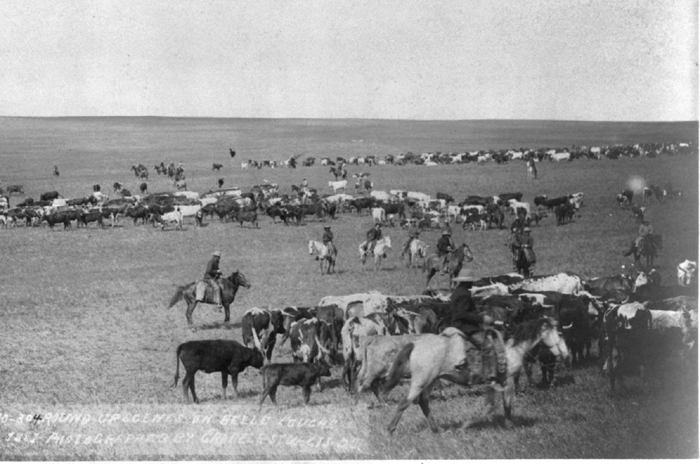

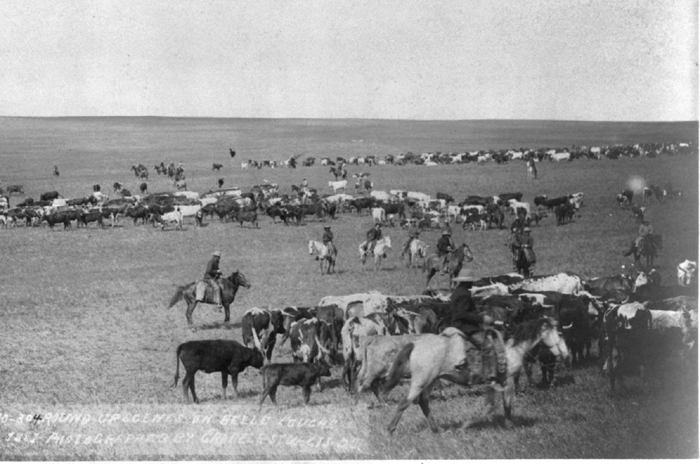

Captain King helped set the pattern for all the cattle drives to come. His trail boss and ten vaqueros herded the half-wild longhorns. A cook drove a chuck wagon stuffed with bedrolls and supplies. A wrangler took charge of the extra horses. A typical drive started in February with a roundup. Herds ranged in size from one thousand to four thousand head. By March, the drive was underway. Spring grasses fattened the longhorns as they moved up the trail.

Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

Cowboys round up stray cattle during the long drive to markets in the Midwest. In the 1860s, Richard King sent his longhorn steers over a thousand miles of prairie from the King Ranch to the Kansas railheads in Abilene. Captain Kings success helped set the pattern for all the cattle drives to come.

Most ranchers paid their trail bosses about $100 a month. Richard had a better plan. His trail bosses took more care with the cattle because they were partners in the drive. Before heading north, a trail boss signed a note for the herd at its Texas value. To that figure Richard added the value of the horses, wagons, and other equipment. Then he gave the trail boss the cash needed to pay wages and purchase supplies. After the cattle were sold and the expenses deducted, the trail boss shared in the profits.

On one drive in 1875, trail boss John Fitch signed for 4,737 cattle and 137 horses. Four months later, Fitch sold the cattle for $18 a head. His share of the profits came to $5,366. Most men worked for years to earn that much money. Raising the cattle had cost Richard less than two dollars a head. He collected $61,886, of which more than $50,000 was profit.

On the King Ranch, only the best cattle went to market. Undersized and poorly developed steers were killed for their hides and tallow. To improve his longhorns, Richard brought in Durham bulls from Kentucky. His goal was to produce a steer with a longhorns toughness and a Durhams bulk. By the 1920s, those early efforts would lead to a productive new breed, the Santa Gertrudis.

In pursuing his dream, Richard King invented modern ranching. Before he came along, farmers tended to raise cattle as a sideline. In the cities, fresh meat was a luxury few could afford. The King Ranch turned ranching into a big business. It also helped turn Americans into a nation of meat eaters.

The story of the King Ranch begins on the high seas. In 1835, the sailing ship Desdemona was four days out of New York. When the crew checked the hold, they found an eleven-year-old stowaway. The sailors hauled the frightened boy to the deck. Under the captains stern gaze, he told his story.

His name was Richard King. He said he was born in New York City on July 10, 1824. His immigrant Irish parents lived in poverty. Neither then nor later did Richard reveal their names. When he was nine, young Richard was apprenticed to a jeweler. Instead of teaching him the trade, the jeweler treated Richard like a servant. The boy swept, cleaned, and scrubbed. He also took care of the jewelers baby.

Boredom led to rebellion. Richard fled the jewelers house and ran to the waterfront. He had learned about stowaways from friendly roustabouts. That night, one of the men helped him hide on the Desdemona. Since then, he had spent four days and nights in the dark hold. His only food had been the sack of bread he brought with him. Was he telling the truth? The record gives us no other data on Richards early life. No one from his family ever claimed him as kin.

Richard begged the captain not to send him back. He was willing to work for his passage, he said. The captain looked down at the small, smudged face. He saw a square jaw, dark hair, and deep blue eyes. The appeal in those eyes touched his heart. He put Richard to work as his cabin boy. His faith was not misplaced. Richard was a hard worker and a quick learner.

Some days later, the Desdemona docked in Mobile, Alabama. The captain, now a good friend, found young Richard a new job. For the next two years, the boy sailed southern rivers on Captain Joe Hollands steamboat. In 1837, Holland chose Richard to be his cub. As a cub, the boy was in training to be a river pilot. The thirteen-year-old had to learn every bend, sandbar, and snag on the Alabama River. In his spare time, the kindly Holland taught Richard how to read.