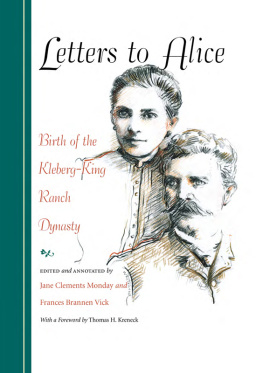

Seventeen-year-old Henrietta Chamberlain stood on the deck of the Whiteville in the stifling, humid air. Everything here at the tip of Texas was so different from other places she had livedthe landscape, the weather, even this houseboat that was their home. Her fathers missionary zeal had brought them to this town, and she was eager to join his efforts, but what a place this was!

Brownsville was less than three years old in 1849. It had grown up around the fort Zachary Taylor established when his troops were at the mouth of the Rio Grande during the war with Mexico. After Major Jacob Brown died there, the fort and the town took his name. Following an epidemic that left only 500 survivors, the town was booming again. Heavy steamboat traffic on the river had turned it into a major port for the southern United States and northern Mexico. There was a post office and market. Numerous stores lined the banks of the Rio Grande. Soon there would be a proper building for her fathers church.

The Reverend Hiram Chamberlain had come to establish a Presbyterian church. The only place available for his family was a houseboat. Undeterred, he held prayer meetings on board the Whiteville until the church building was ready.

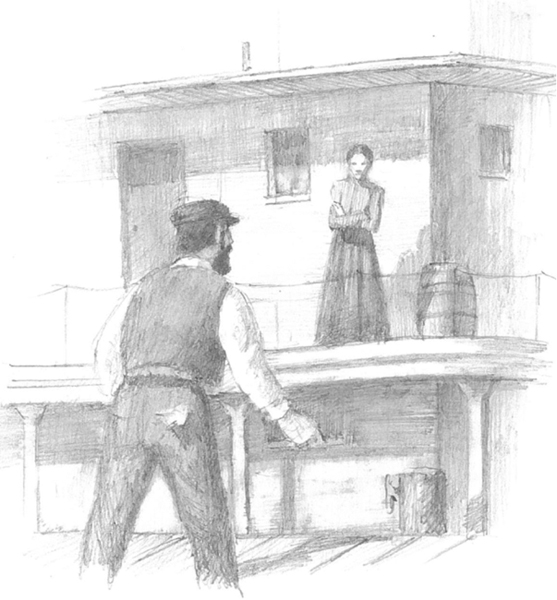

The slight young woman turned at the noise of a steamer approaching. Suddenly a string of profanity burst from the steamer wheelhouse. The tortuous journey down the Rio Grande had not improved the temper of the tall, dark-haired captain. He stepped out and unleashed his fury at the imbecile who had dared dock in his usual place.

Offended by his language, Henrietta informed the captain in icy tones that no gentleman spoke that way.

Such a rebuke from a man would have brought Richard Kings fists smashing into the offenders face. Instead, the twenty-five-year-old captain with the razor-quick temper could only stare at the indignant young woman. He clamped his mouth shut, backed his boat away, and docked at another spot, leaving the five-foot-three-inch, ramrod straight figure standing on the deck of the Whiteville.

It was not love at first sight. But then again, maybe it was.

Henrietta Morse Chamberlain, born July 21, 1832 in Boonville, Missouri, was the daughter of Reverend Hiram and Maria Morse Chamberlain. Her mother died before she was three years old, and Chamberlains second wife, Sarah Wardlaw, had died childless. His third wife, Anna Adelia Griswold, would give him eight children. They had buried three infants before they reached Texas.

Hiram Chamberlain had a profound influence on Henriettas life. The ideals and principles he instilled in her were the basis of Henriettas lifelong code of conduct. Chamberlain, a native of Vermont, graduated from Princeton Seminary and was an ordained Presbyterian minister. He had a special zeal to preach the gospel to the poor and ignorant of his own land. The family moved many times as he served various churches in Missouri and Tennessee.

When Henrietta was fourteen, he sent her away to school at the Holly Springs Female Institute in northern Mississippi. The headmaster of the Presbyterian school was fellow seminarian James Weatherby. The school promised to provide a thorough and complete education, aiming at development of intellectual powers, formation of the deportment of the most correct walks of society, cultivation of right motives Christian Morals shall be the prominent feature of instruction.

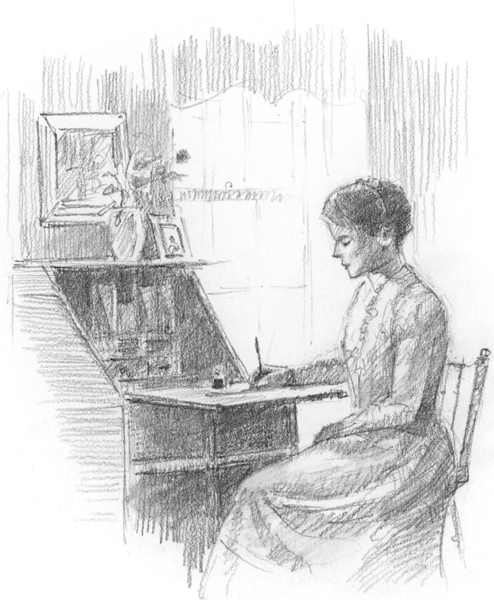

Henrietta and some ninety classmates studied grammar, arithmetic, history, and foreign languages. Music lessons and art instruction were also available. Henrietta wrote poetry and painted flowers on white velvet.

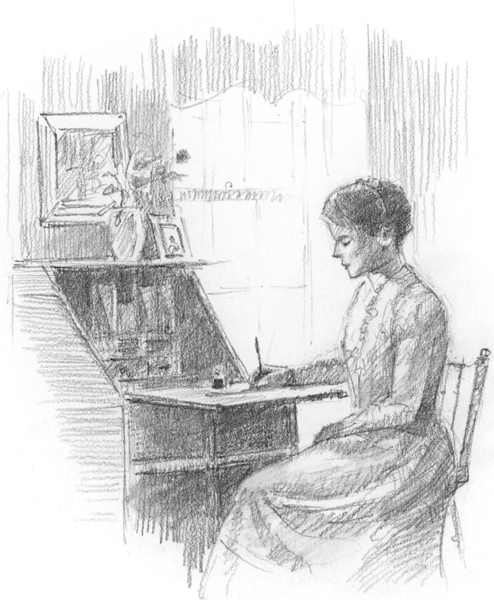

During the two years Henrietta was there, her father wrote frequently. His long letters were dictated by the purest affection, and the most unfeigned anxiety for your welfare, and improvement, your happiness and usefulness in the world. Besides family happenings, the letters touched on a wide range of subjects from womens rights to temperance, theology, even personal habits. Sit up straight, he admonished, and dont allow yourself to sit in a stooping posture. That will make you round shouldered and ruin you. He encouraged her to read the Bible every day. The very best knowledge in the world is that which is derived from the Bible.

Henrietta dearly loved her little half-brothers Hiram Jr. and Bland. At school she was very homesick to see them. She sent Hiram Jr. a little book. Her father reported that his son pretended to read it, and was much pleased that you sent it to him. He professes to understand what you say about him, and becomes very animated. At the same time, he cautioned her to get over being homesick. That will never doIt will injure your health, and your mind.You must determine to get above it.We were not made to be perfectly happy here. We must wait till we get to heaven for that. Her stepmother, with a little more sympathy, enclosed an expensive handkerchief as a present.

Henrietta profited from her fathers advice. By the time she arrived in Brownsville she was a calm, efficient, educated young woman of great dignity. The rough language of the riverboat captain shocked her, but she put the whole incident out of her mind.

Twenty-five-year-old Richard King was still smarting from the encounter when his partner James Mifflin Kenedy boarded his vessel. Kenedy, a soft-spoken Quaker, was seven years older than King. Friendship between two such radically different persons would not have seemed possible, but both men respected the integrity and hard work of the other. They forged a bond that lasted a lifetime.

Richard King, born in New York City and orphaned at six, ran away from an apprenticeship at age eleven. He stowed away on a ship and began working on river boats. The only formal education he had was the eight months a sympathetic captain sent him to school in Connecticut. Returning to steamboating on southern rivers, he quickly distinguished himself as a river pilot. Never yielding an inch to anyone, he earned a reputation for fighting and drinking. By age nineteen he was a licensed riverboat captain and had caught the attention of Mifflin Kenedy.