Contents

Guide

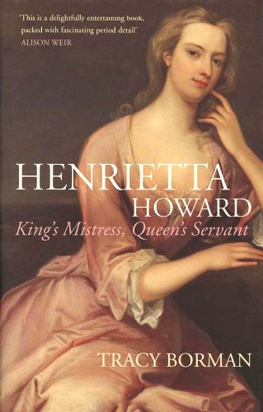

The Warrior Queen Who Divided a Nation

Henrietta Maria

Leanda de Lisle

New York Times Bestselling Author of Tudor: Passion, Manipulation, Murder

For Cosima

Cherchez la femme

Alexandre Dumas

List of Illustrations

First Plate section

Second Plate Section

Preface

Here are some of the things I have often read and heard said about Henrietta Maria: she was frivolous, extravagant, had bad teeth and skinny arms; she was an adulteress who secretly married Henry Jermyn; she was implacably Catholic, she made King Charles Catholic and caused the Civil War; later she proved to be an unloving mother to her son, Henry, Duke of Gloucester, whom she tried to make Catholic because she was a bigot, and finally, at the Restoration she was an irrelevance, nothing more than a shrivelled and miserable old lady. She was, in short, the classic witch-Eve.

Frivolous so morally weak Henrietta Maria had been corrupted by the papal Antichrist as Eve was by Satan. Bearing the disfigurement of sin, glimpsed in her bad teeth, she spent extravagantly on clothes and perfumes to project a false beauty which she used to seduce Charles into evil, and so brought sorrow and death to the demi-paradise of England. We not only accept parliamentary propaganda from the past for example that Henrietta Maria wore the breeches in her marriage we have promoted new myths to support it. Charles is often described, entirely inaccurately, as a physical weakling and a fop. Nor can she be associated with royalist victory at the Restoration.

This is supported, but only by selective quotation so we have, for instance, the diarist Samuel Pepys describing Henrietta Maria when he first saw her, still grieving over the death of her son Henry, dressed in black, looking very ordinary, and not his later descriptions of her court as more merry than that of the merry monarch, Charles II.

The familiar tropes connected to Eve predate the Reformation and are still used against women of all kinds. But our attitude to Henrietta Maria is also clearly linked to our confessional history. The term popish, much bandied around in the seventeenth century, referred to a form of political and spiritual tyranny which hotter Protestants associated with the Catholic Church, but which was deployed quite broadly, often against anti-Puritans. The Catholic association alone remains embedded in our national psyche.

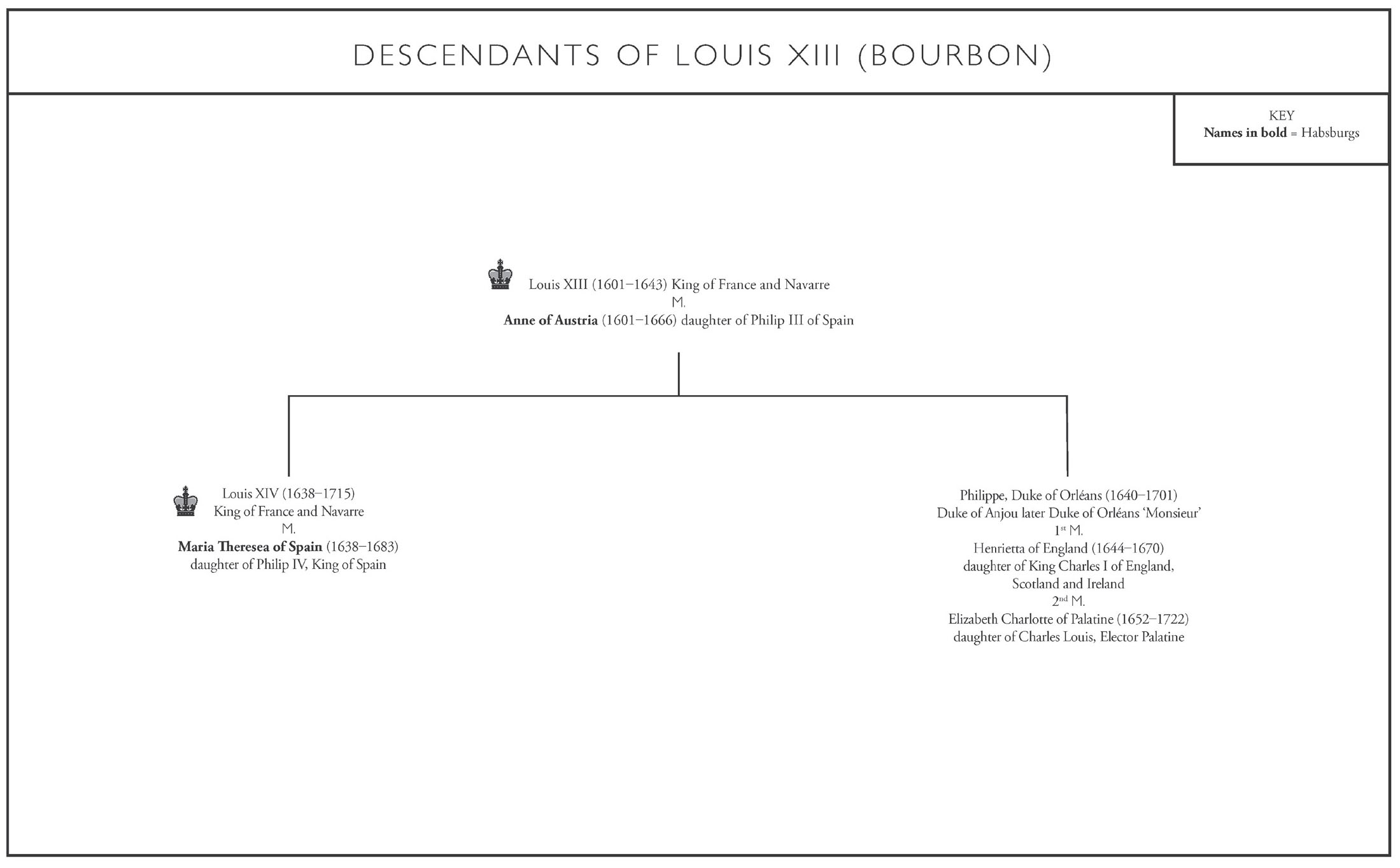

The belief that Protestantism is responsible for the work ethic that built the empire and the emergence of democracy are amongst our most treasured national myths. The converse of this is that Henrietta Maria, the popish Catholic, must be responsible for Charless authoritarianism. We have bought into the deep state conspiracy theories of the seventeenth century. We have also forgotten the complexity and contradictions of the past. Many of those who fought hardest for liberty against Charles denied it to the slaves they shipped from Africa to the Americas, and to the Catholic Irish they cleansed from their lands. There was no monopoly on virtue or sin. Henrietta Marias story would not have interested me, however, had it only allowed me to say what she was not: not frivolous, not a fanatic, not weak, not responsible for the Civil War, not an unloving mother though I am pleased to do so. The interest is rather in revealing the story of who she was and what drove her.

From popish brat to Phoenix Queen I hope her character will emerge in all its light and shade: capable of great kindness, especially to lowly servants, yet also brutally frank, not least with her husband, she was a warrior and a wit, had an acute sense of the ridiculous but also a spiritual inner life that gave her gravitas. She struggled with the admonition to obey her husband and her son as heads of their households and as kings, yet both loved her, and if she could not win their battles for them, no one could have fought harder to do so.

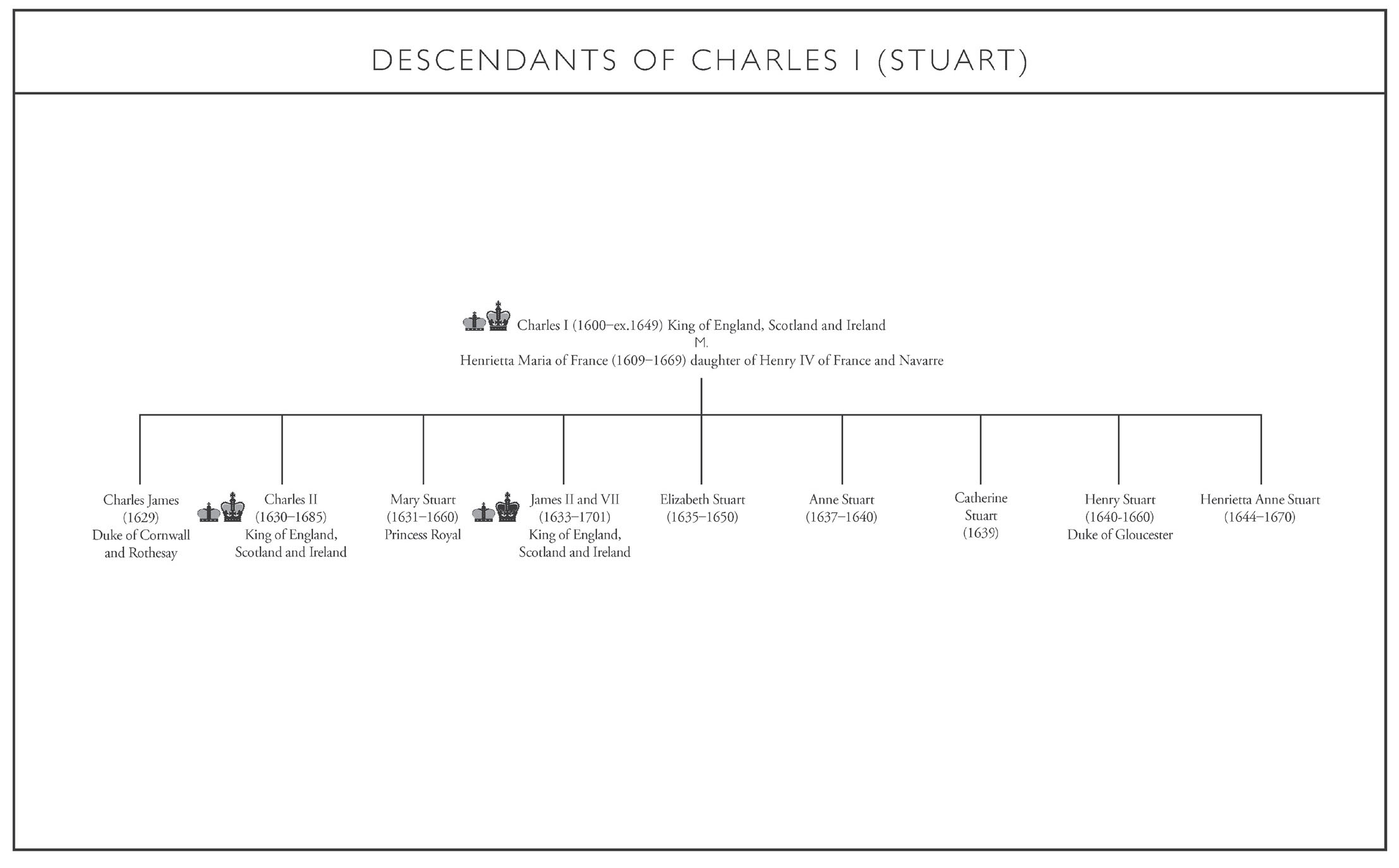

My biography of Charles I, White King, attempted to look at Charless reign and the Civil War from his point of view. It asked what was the divine right of kings and why did he believe in it? What were his religious beliefs and how did they differ from those of his opponents? Who was the man behind the myths? Why did he behave the way he did? Henrietta Maria was a very important part of his life and I learned that readers enjoyed being introduced to a dynamic queen who was a significant political player. This book tells the story of her life from her point of view.

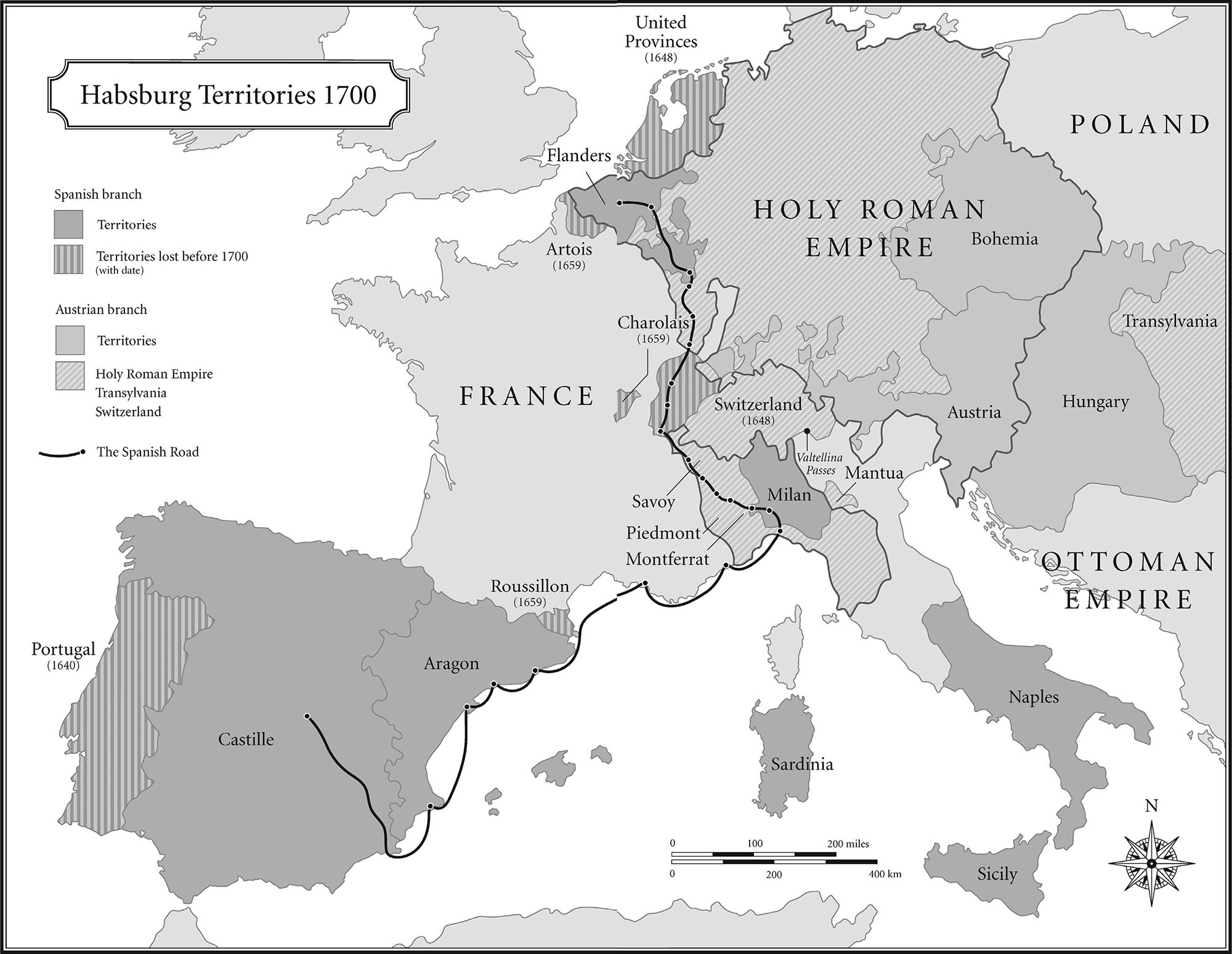

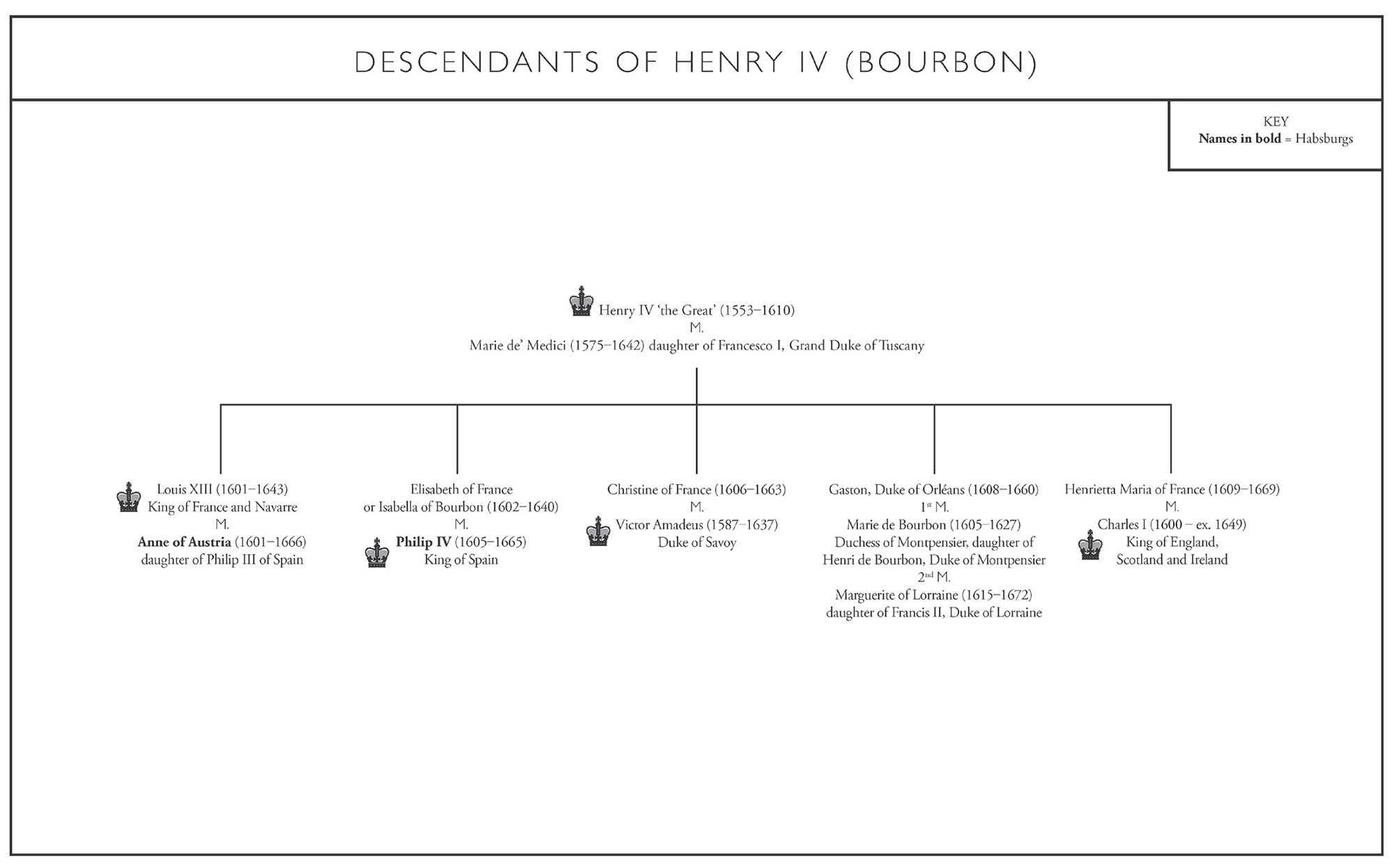

Although Henrietta spent less than half her life in England with Charles, inevitably there will be a crossover with White King. That poses particular difficulties for a writer. I have used a combination of adding new material and trimming old to reshape those sections of the narrative in line with the queens perspective. Those hoping to meet her great frenemy Lucy Carlisle again will not be disappointed, but there is now a larger cast of women. Indeed another challenge has been the scale of the story. I introduce Henrietta Maria as the Bourbon princess, born into the society of princes who ruled Europe. British history is too often told in isolation, but what happened here cannot be understood without some knowledge of what was happening there. Henrietta Marias world is one where family quarrels are fought out with armies bringing death to villages, cities, even whole regions. It is also a time when rulers might be killed by their own subjects and co-religionists, if they do not consider them Catholic enough, or Protestant enough.

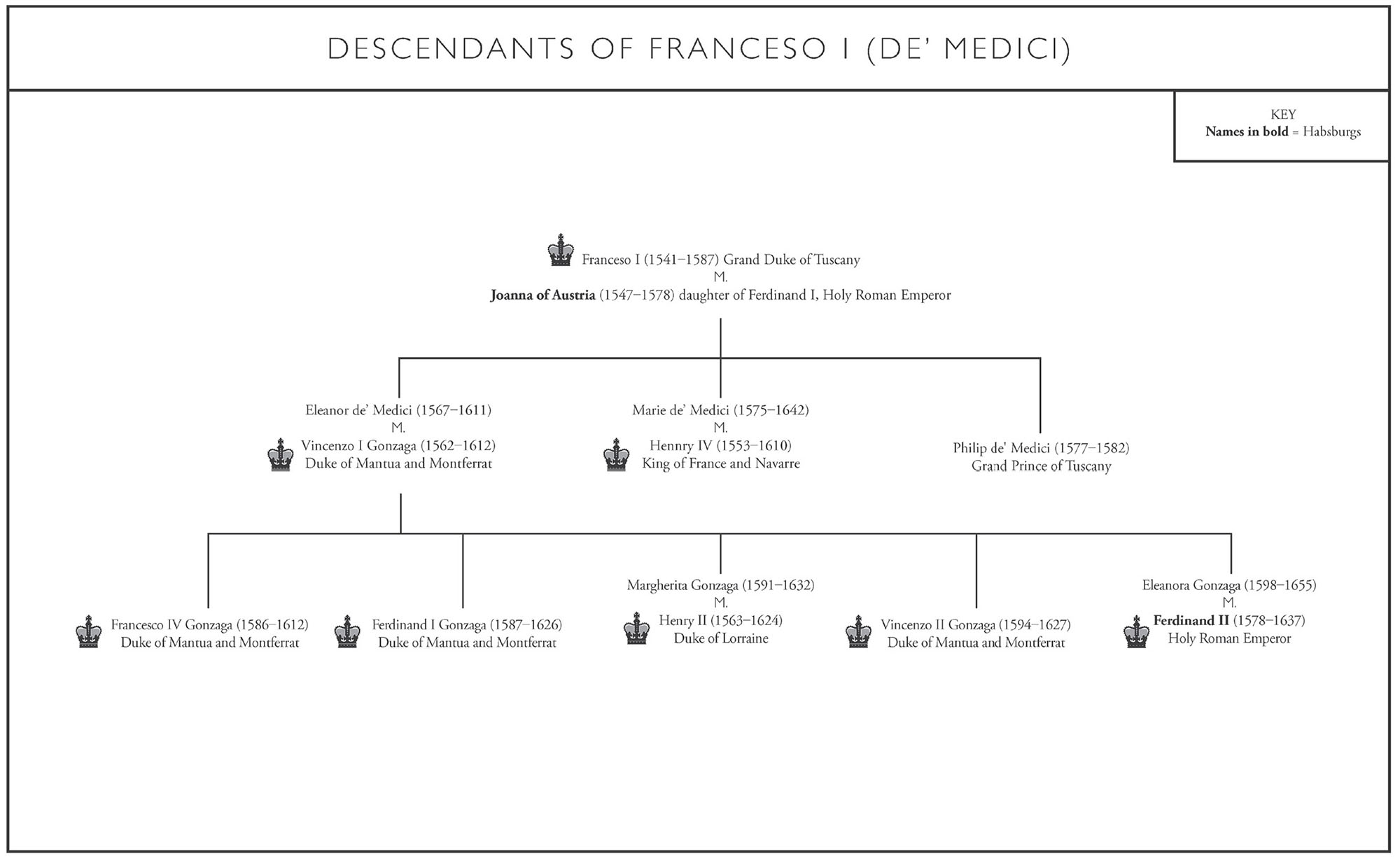

Henrietta Maria was not yet six months old when her father, the great warrior king Henry IV of France, was assassinated by a Catholic fanatic who disapproved of his alliance with Protestants against the Catholic Habsburgs. She was said to have been very like Henry and she would often invoke her fathers name as an example of physical courage and in his friendships to Catholics and Protestants. In this she saw herself very much as his daughter. Her marriage to Charles represented another alliance with a Protestant power aimed against the Catholic Habsburgs. Her enmity to that dynasty contrasted with the BourbonHabsburg friendship her mother wanted.

Yet Henrietta Maria, named after both her parents, was also very much the daughter of Marie de Medici. As Henrys consort Maries influence in France set the standard in Europe for centuries to come on court manners, theatre, luxury goods, and the art of haute cuisine a standard her daughters would seek to follow. As a widow and ruler Marie showed great confidence in what a woman was capable of, exercising power in a mans world, without apology a crime for which she has yet to be forgiven.