He Led the Way

As winter strangled the wilderness, John C. Frmont needed to get his expedition party to California. Facing sub-zero temperatures, meager food supplies, and American Indian warriors on their trail, the explorer counted on one man to lead the way: Kit Carson. The mountain man and scout knew the uncharted West better than anyone. Carson led the party through the deep snow over the Sierra Nevada Mountains to their destination. Frmont reported Carsons courageous deeds and exceptional skills, and the mountain man became a national hero. Authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green explore the life of this American frontier legend.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

This book tells the true story of Kit Carson. Kit was one of the Wild Wests greatest heroes. In his day, he was known as an outstanding scout, mountain man, and Indian fighter. His skill, bravery, and daring exploits were featured in newspapers, magazines, and dime novels. In more recent years, Kit has been featured in novels, films, biographies, and on television. You may be amazed that one man could pack so much adventure into a single lifetime. If so, rest easy. All of the events described in this book actually happened.

In the early 1840s, much of the West was still unexplored. John Charles Frmont and Kit Carson took on the task of mapping the vast region. Frmont was on his way to becoming the foremost explorer of his day. Kit was a little-known scout and mountain man. That changed when Frmonts reports reached the public. The stories he told of Kits skill and courage turned him into a national hero.

Late in 1843, Kit was Frmonts guide on a trip to Oregon country. By years end, the expedition had turned south toward the eastern Sierra Nevada in present-day Nevada and entered the Great Basin. A search for the fabled Buenaventura River drew a blank. No such river flowed through the mountains to the West Coast. Christmas brought little cheer. A small ration of brandy could not drive out the chill.

In mid-January, Frmont held a council. The party could not turn east, Frmont said. That route led over jagged rocks that would cripple their mules. If they stayed where they were, they would starve or be killed by warlike American Indians. The smoke of signal fires already rose from the nearby heights. Their best bet was to head west toward California. Frmont counted on Kit to find a way through the Sierra.

Every mile was a struggle. At night, the temperature dropped to 2F (19C). Mountain streams froze over. The men had to break the ice so the mules could drink. American Indians appeared, eager to trade pine nuts for mirrors and beads. Asked to serve as guides, they told Kit to wait for spring. No one can cross the mountains in winter, they warned.

Kit roused the sleeping camp at 3 A.M . each day. The early start allowed the pack train to plod forward on hard-crusted snow. The men wore crude snowshoes. As the day wore on, the crust softened. Horses and mules would flounder in deep snow. Kits work crew had to beat the snow with mallets to make a usable trail. Frmont had hauled a small cannon all the way from St. Louis. Now he left it behind in a snowbank.

Animals and men went hungry. The starving mules chewed on their harnesses. When a mule died, the men dined on the carcass. At one point, Frmont allowed the cook to grill the partys dog. The menu that night featured pea soup, mule, and dog.

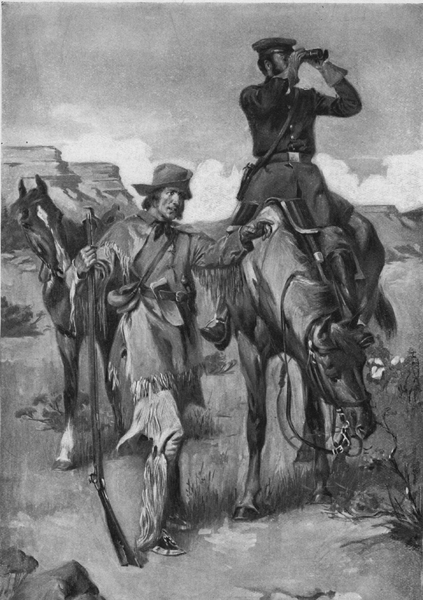

Image Credit: The New York Public Library / Art Resource, NY

John C. Frmont (right) counted on Kit Carson (left) to guide his expedition across the rugged Sierra Nevada to reach California.

Kit did his best to keep spirits high. He told the men, Thar over the ridge lies the purtiest valley in the world. I know it, cause I war thar fifteen years ago. The climb took the expedition through a pass at 9,338 feet. Frmont named it Carson Pass in honor of his guide. On February 1, Kit spotted a range of mountains that he knew. Two more weeks, he told Frmont, would take them to the Sacramento Valley.

Kit led the way down steep hillsides to a shallow stream. Always sure-footed, he jumped across. Frmont was not as agile. His moccasins slipped, and he fell into the icy water. Thinking Frmont was hurt, Kit jumped in to rescue him. After both men regained their footing, they searched in vain for Frmonts rifle. At last, chilled to the bone, they climbed out. Kit built a fire to drive out the damp and the cold.

The weary men rejoiced when they reached the valley floor. The weakest men and animals stayed there to rest. Kit led Frmont and the others to Sutters Fort on the Sacramento River. On March 6, Captain Sutter rode out to greet the weary explorers. They were the first, he told them, to cross the Sierra Nevada in midwinter. Perhaps Sutter should not have been surprised. Kit Carson was one of the greatest mountain men who ever lived.

Christopher Houston Carson was born in Kentucky on Christmas Eve, 1809. Right from birth he was called Kit. His mother, Rebecca, was Lindsey Carsons second wife. Lindseys first wife, Lucy, had five children before she died. Rebecca had ten more.

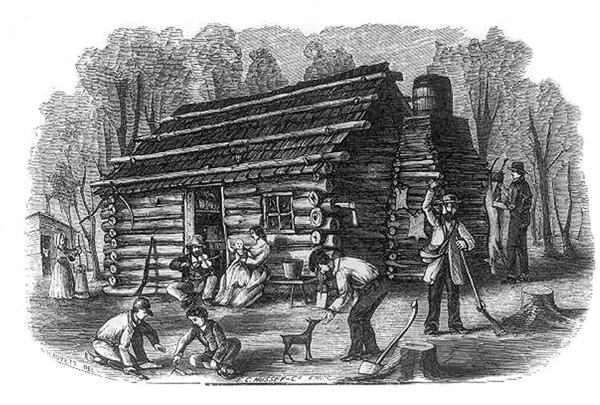

The Carsons lived in a log cabin warmed by a huge fireplace. The main room served as the kitchen, dining, and living room. The children climbed a ladder to their beds in a sleeping loft. Travelers from the West sometimes bedded down near the fireplace. They paid for their suppers with tales of cheap land and high adventure.

In 1811, the Carsons joined the westward move-ment. Lindsey settled in Howard County, Missouri. This was frontier country. When the American Indians went on the warpath, the settlers crowded into crude forts. Life was hard, but very few complained. As one settler wrote: No man owing a dollar, no taxes to pay, we lived happy and prosperous.

Kit was small, with wavy blond hair that fell across a high forehead. Like most boys, he loved to hunt and fish. Unlike his friends, he studied the local American Indians. The knowledge and skills he picked up came in handy all through his life.

Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

This illustration shows a pioneer familys log cabin on the Missouri frontier in 1820. Lindsey Carson, Kits father, moved the family to Howard County, Missouri, in 1811, while Kit was still a baby.

Kits father saw that his son had a quick mind. Maybe the boy would grow up to be a lawyer. The dream vanished the year Kit was eight. Lindsey was clearing his land when a tree limb fell and killed him. With his father dead, Kit had to quit school. Later, he joked about his three years in the classroom. As he told a friend, I was a young boy in the school house when the cry came, Indians! I jumped to my rifle and threw down my spelling book, and there it lies.

Four years later, Kits mother married Joseph Martin. Like many teenagers, Kit was hard to control. When he was fourteen, Martin put him to work in a saddle-makers shop in Old Franklin, Missouri. David Workman, the owner, treated Kit fairly, but the boy yearned for the outdoor life.