I Always Tried My Best

Angry mobs had forced Brigham Young and his fellow Mormons out of Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois. As leader of the Mormon Church, Young needed a safe place for his followers to live and worship freely. So with more than 5,000 Mormon settlers, Young crossed prairies, climbed mountains, and overcame hardship to reach his Promised Landan unsettled region near the Great Salt Lake of Utah. Sometimes called the American Moses, authors William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green explore the amazing life of this great pioneer.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

This book tells the story of one of the Wild Wests most unusual heroes. As a pioneering leader of the Mormon Church, Brigham Young had to be a preacher, farmer, builder, statesman, and family man. As you will learn, he excelled in all of these tasks. Because his ideas and actions aroused strong feelings among both Mormons and non-Mormons, reports of his activities filled the newspapers of the day. As often happened in the 1800s, some of the stories stretched the truth. All of the events described in this book actually happened.

In July 1857, the Mormon settlers of Utah Territory awoke to a new threat. The United States was sending troops to install a new governor. Would they be forced to flee once again? They turned to Governor Brigham Young for guidance. Ten years before, Brigham had led them to their new home beside the Great Salt Lake.

Brigham knew that the Mormons and their church, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, had few friends in Washington, D.C. Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois was leading the attack. Douglas called the Mormon way of life a cancer gnawing into the very vitals of the [American] body politic.

President James Buchanan had his own reasons for sending troops. The slavery issue divided the nation. An attack on the Mormons might turn attention away from that fierce debate.

Image Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs

This portrait of Brigham Young was taken sometime between 1855 and 1865.

Out in Salt Lake City, Brigham weighed his options. On his desk lay an offer of 30 million acres in Central America. To the north lay Canada and Alaska. The army, however, would arrive before his people could move. So, early in August, Brigham announced, We have transgressed no law as for any nation coming to destroy this people, God Almighty being my helper, it shall not be.

Workmen built forts at the entry points to the Salt Lake Valley. To slow the advancing troops, Brigham sent soldiers to cut off their supply line. The raiders burned three wagon trains and drove off a number of horses. They also burned two outposts. The raids, combined with early snowfalls, finished the job. The advancing troops were forced to set up winter camp in Wyoming.

When shooting did break out, it had nothing to do with Brigham. A party of settlers bound for California had reached southern Utah that same month. Riding with the wagon train was a band of horsemen known as the Missouri Wildcats. A local tribe of American Indiansthe Uteblamed the Wildcats for poisoning their wells. Mormons were equally outraged. Back in Illinois, the Wildcats bragged, they had helped kill the churchs founder, Joseph Smith.

In southern Utah, Mormon and Ute hotheads planned revenge. Unsure of what to do, church elders sent word to Brigham. A rider covered the 250 miles to Salt Lake City in three days. Brigham replied at once. His orders read: You must not meddle with them [the settlers]. The Indians we expect will do as they please.

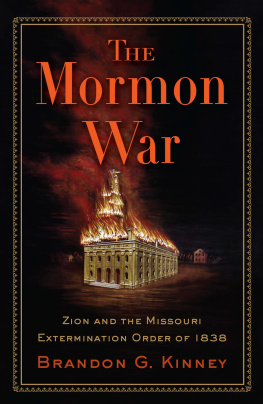

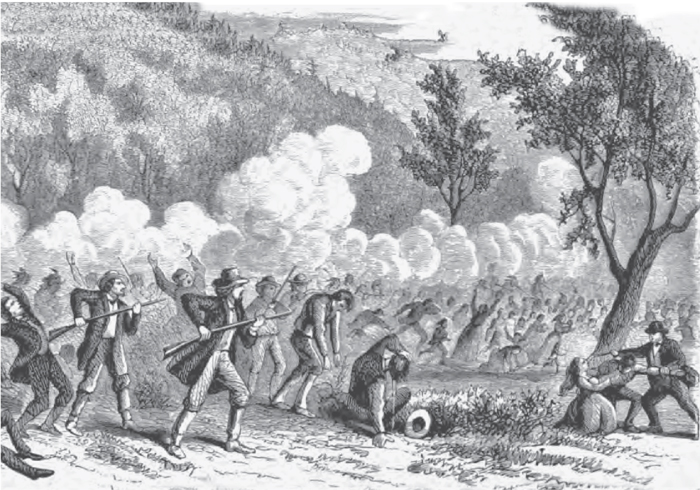

Image Credit: Public Domain Image

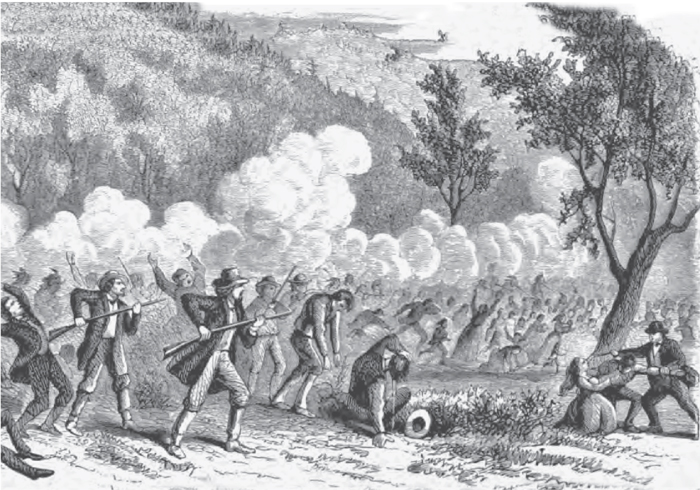

In 1857, Brigham Young sent word to his Mormon followers not to attack a wagon train headed for California. His dispatch, however, arrived too late. This illustration depicts the Mountain Meadows massacre, in which a force of Mormons and Ute warriors killed 120 settlers.

The dispatch arrived too late. On September 11, a force of Mormons and Ute warriors attacked the wagon train. When the Mountain Meadows massacre ended, 120 men, women, and children lay dead. Only seventeen small children survived. Brigham wept when he heard the terrible news. Did he know the depth of his militias involvement? No one knows. To protect his people, he laid the blame on the Ute. The full truth did not emerge until years later.

The threat of invasion still haunted Brigham. As the winter wore on, he changed his tactics. First, he ordered his militia to end its attacks on the armys supply lines. Then he offered to step aside in favor of President Buchanans choice as governor. Alfred Cumming agreed to enter Utah without an army escort. He reached Salt Lake City in April 1858.

In June, President Buchanan announced a full pardon for all Mormons. For his part, Brigham said the army could march through Salt Lake City. That act fulfilled the presidents orders to occupy Mormon lands. As a safeguard, Brigham ordered Mormons to leave the city. Only a few trusted men stayed behind. They had orders to burn the city if the army set up a base there.

On June 26, the troops passed through a nearly silent city. To the south, thousands of Mormons waited and prayed. To their joy, the troops turned south to Cedar Valley. With the threat past, the settlers returned to their homes and farms.

In July, Brigham announced that the Utah War was over. It was one more triumph in a long and active life.

John Young served in George Washingtons army during the American Revolution. After the war, he married Nabby Howe. By 1800, Nabby had given birth to five daughters and three sons. When his farm in upstate New York failed, John bought land in Whitingham, Vermont. Six months later, on June 1, 1801, Nabby gave birth to the Youngs ninth child. They named the boy Brigham.

Vermonts rocky soil defeated Johns best efforts. He and his older sons had to work as hired hands to pay their debts. The girls wove and sold straw hats. To make bad times worse, Nabby fell ill with tuberculosis. The work of raising Brigham and the younger children fell to Fanny, their fourteen-year-old sister.

In 1804, John bought virgin land near Smyrna, New York. He labored hard for weeks to clear the land for planting. As soon as he was old enough, Brigham took over his share of the chores. Money was in short supply. Later, Brigham recalled, If I had on a pair of pants that would cover me I did pretty well.

The Smyrna farm failed, too. In January 1814, the Youngs moved fifty miles farther west. There was little money for schooling. Brigham later said he spent only eleven days in a classroom. His mother taught him to read and write. He spent his spare time hunting and fishing to help feed the family. Sundays were reserved for worship. As strict Methodists, the Youngs were not allowed to dance or listen to fiddle music.

Brighams mother died in June 1815. With his older sisters married, Brigham was saddled with household duties. He baked bread, churned butter, and washed dishes. In 1817, John Young married a widow with several children. There was little room for Brigham in the new household. John told his sixteen-year-old son, You can now have your time; go and provide for yourself.