A Real American Hero!

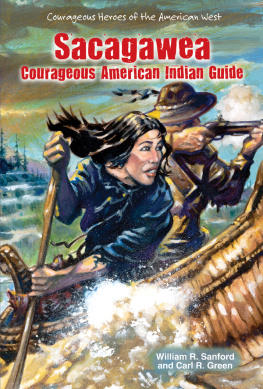

In May 1805, as the Lewis and Clark expedition paddled up the Missouri River, a howling gust of wind suddenly tipped over one of the canoes. The men paddled to shore, leaving behind precious supplies. But Sacagawea jumped in the water, rescuing important journals and equipment. Throughout Lewis and Clarks journey in the uncharted American West, this young American Indian woman proved to be an invaluable member of the expedition. Sacagawea served as translator and guide, all while caring for her infant son. Sacagaweas life may have been short, but her exploits on this monumental mission made her an American hero.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

In 1804, President Thomas Jefferson ordered Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to explore the American Northwest. On their way west, the explorers hired guides and interpreters. One was a French fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau. Lewis and Clark also obtained the services of Sacagawea, Charbonneaus young American Indian wife. It is this brave and resourceful young Shoshone woman who is most likely to capture our attention today.

Some writers have given Sacagawea credit for guiding Lewis and Clark to the Pacific coast. That was impossible. She had never been west of the Rocky Mountains. Sacagawea did serve as a guide and translator while traveling through regions she knew. Further, when Lewis and Clark met American Indian tribes, her presence helped prove that the white men came in peace. These contributions, combined with her wilderness skills, made her a valued member of the expedition.

In many books, writers spell Sacagaweas name with a jSacajawea. In this book, the authors spell her name with a g. This is the spelling that Lewis and Clark used when writing their journals. However her name is spelled, you are about to read Sacagaweas true story. It is based on the expeditions journals and on American Indian oral histories.

In 1805, the United States was looking westward. Two years earlier, President Thomas Jefferson had purchased the Louisiana Territory. The new nation now stretched from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains. Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were pushing deep into the Northwest. Their goal was to open a route to the Pacific.

On August 17, the Corps of Discovery was fifteen months out of St. Louis. It was a crucial time. The Rocky Mountains loomed ahead. Soon, their canoes would be useless. Lewis and Clark needed horses. The Shoshone were nearbyand the tribe bred fine horses.

Each American Indian tribe raised a new challenge. Some chiefs welcomed the white men. Others treated them as enemies. The captains had less reason to fear the Shoshone than the other tribes. Traveling with them was a Shoshone woman named Sacagawea. Taken captive as a child, she had grown up in a Hidatsa village to the east.

Sacagaweas husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, served as an interpreter. He did not speak Shoshone. Lewis and Clark were counting on the young wife and mother to interpret for them. That morning, she was picking berries near the Beaverhead River. Pomp, her infant son, rode in a cradleboard on her back.

All at once, Sacagawea spotted several Shoshone on horseback. The sight caused her to dance for joy. Turning, she put her fingers in her mouth. Clark read the gesture as meaning the riders were from her tribe. Astonished by her return, the Shoshone led the explorers to their camp. One of the white men described the meeting. As the party neared the camp, a woman made her way through the crowd toward Sacagawea. Recognizing each other, they embraced with the most tender affection. They had been companions in childhood. Like Sacagawea, Willow Woman had been taken captivebut she escaped and found her way home.

That afternoon, the American captains met with Chief Cameahwait. A sail from one of the dugout canoes shaded the men from the sun. The chief seated Clark on a white robe. Then he tied six small shells in Clarks red hair. As a further sign that the two groups met in peace, the men took off their moccasins. A sacred peace pipe passed from hand to hand.

Image Credit: Marilyn Angel Wynn / nativestock.com

In this illustration, Sacagawea poses with her son Pomp resting in a cradleboard at her side. When the Lewis and Clark expedition reached the Beaverhead River, Sacagawea met several Shoshone on horseback. Her reunion with her people was a joyous occasion for the young Shoshone woman.

Now it was time to talk. Lewis sent for Sacagawea to interpret. Without her, the council could not proceed. She entered the circle with her eyes cast down as a mark of respect for the tribes elders. When the captains spoke, Charbonneau repeated their words in Hidatsa. Sacagawea then translated their comments into Shoshone.

Sacagawea sat near Clark, who made a speech that explained the purpose of his journey. Sacagawea looked upand recognized the chief. Cameahwait was her older brother! She jumped up and threw her blanket around him. Then she wept as she hugged him. Brother and sister talked briefly. Sacagaweas tears of joy flowed freely as she returned to her seat.

Later, Sacagaweas happiness turned to sorrow. Most of her family had died. Only Cameahwait and her sisters son had survived. As custom required, she adopted the boy. Then she gave him to his uncles to be raised. At that point, an older warrior stepped forward. Sacagaweas father, the man claimed, had given her to him in marriage. He dropped his claim when he learned that Pomp was Charbonneaus child.

With Sacagaweas help, Lewis and Clark bought a string of packhorses. On August 27, they gave the command to move out. Sacagawea said farewell to her brother. She never saw him again.

Sacagaweas adventurous life began in Idahos Lemhi River valley. Her father was a chief of the Shoshone. The tribal name means People who live in the valley. Her year of birth was 1788. No one knows the day or month. It may have been in March, the Moon of the Rushing Waters.

It was common for American Indians to have more than one name during their lifetimes. Sacagaweas name at birth was Bo-i-naiv (Grass Maiden). The Hidatsa renamed her Sacagawea. That was the name Lewis and Clark knew her by. It translates as Bird Woman. In later years, she may have also been called Lost Woman, Porivo (Chief), and Water White-Man.

The Shoshone wandered north from Mexico hundreds of years before Sacagawea was born. For a time, the tribe lived in the Great Basin between the Sierra Nevada and the Rocky Mountains. Then came a searing drought. As game animals left the basin, the Shoshone became nomads. Always on the move, they ate salmon, squirrels, rabbits, rats, and lizards. The children gathered roots, seeds, and berries. When hunters came home with empty hands, the women roasted crickets and grasshoppers. Water was scarce. Little could be spared for bathing.

In summer, the Shoshone dressed lightly. Men wore a breechcloth of badger hide. Women wore a leather apron. Men and women walked the rocky trails in yucca fiber sandals. Their homes were crude brush shelters called wickiups. When winter swept the basin, the Shoshone put on leggings, moccasins, and rabbit-fur capes.