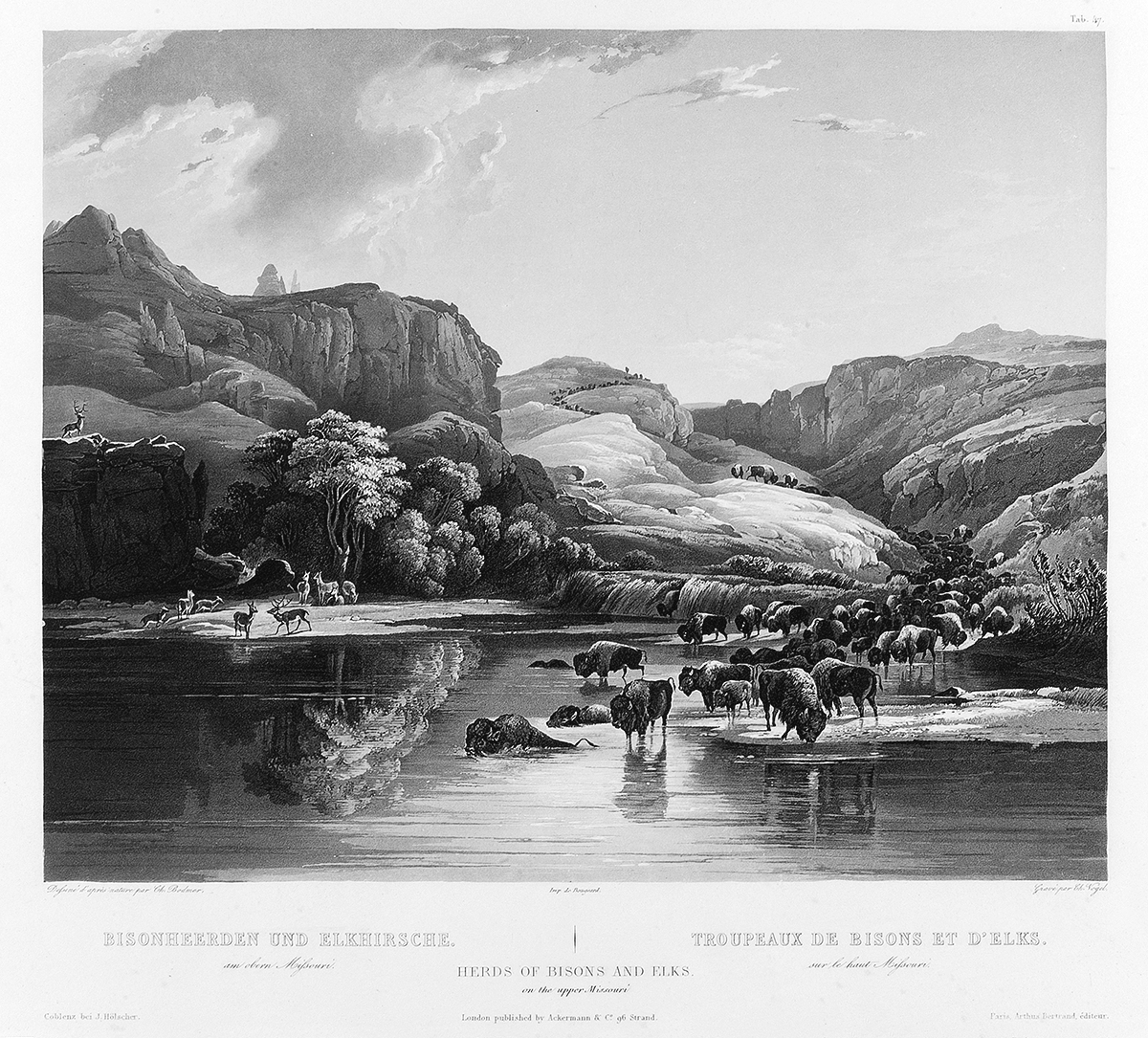

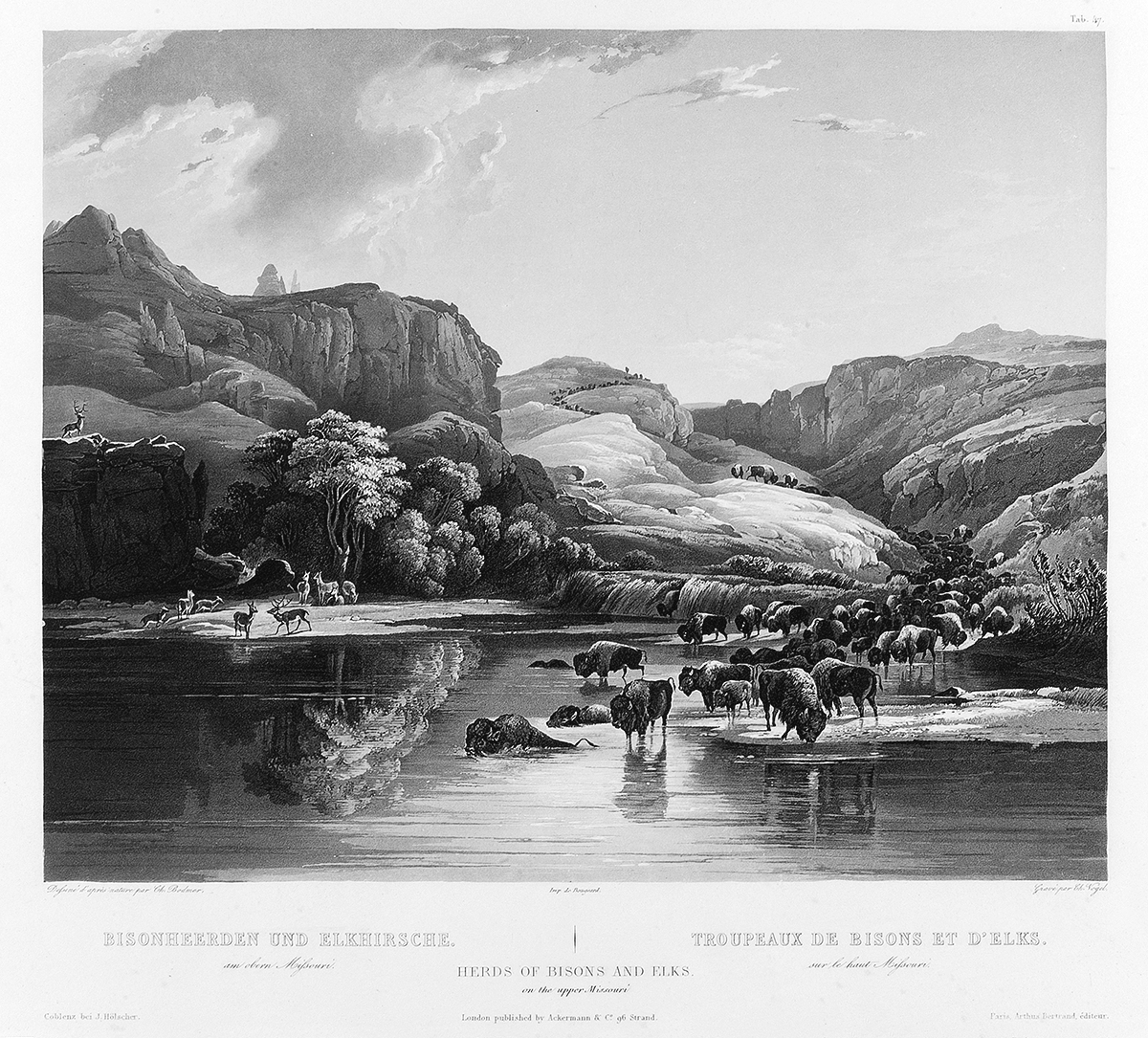

Karl Bodmer (18091893). Herds of Bisons and Elks on the Upper Missouri. Aquatint and etching, ca. 18401844. Courtesy of the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas. 1965.169.65.

Copyright 2017 by David Weston Marshall

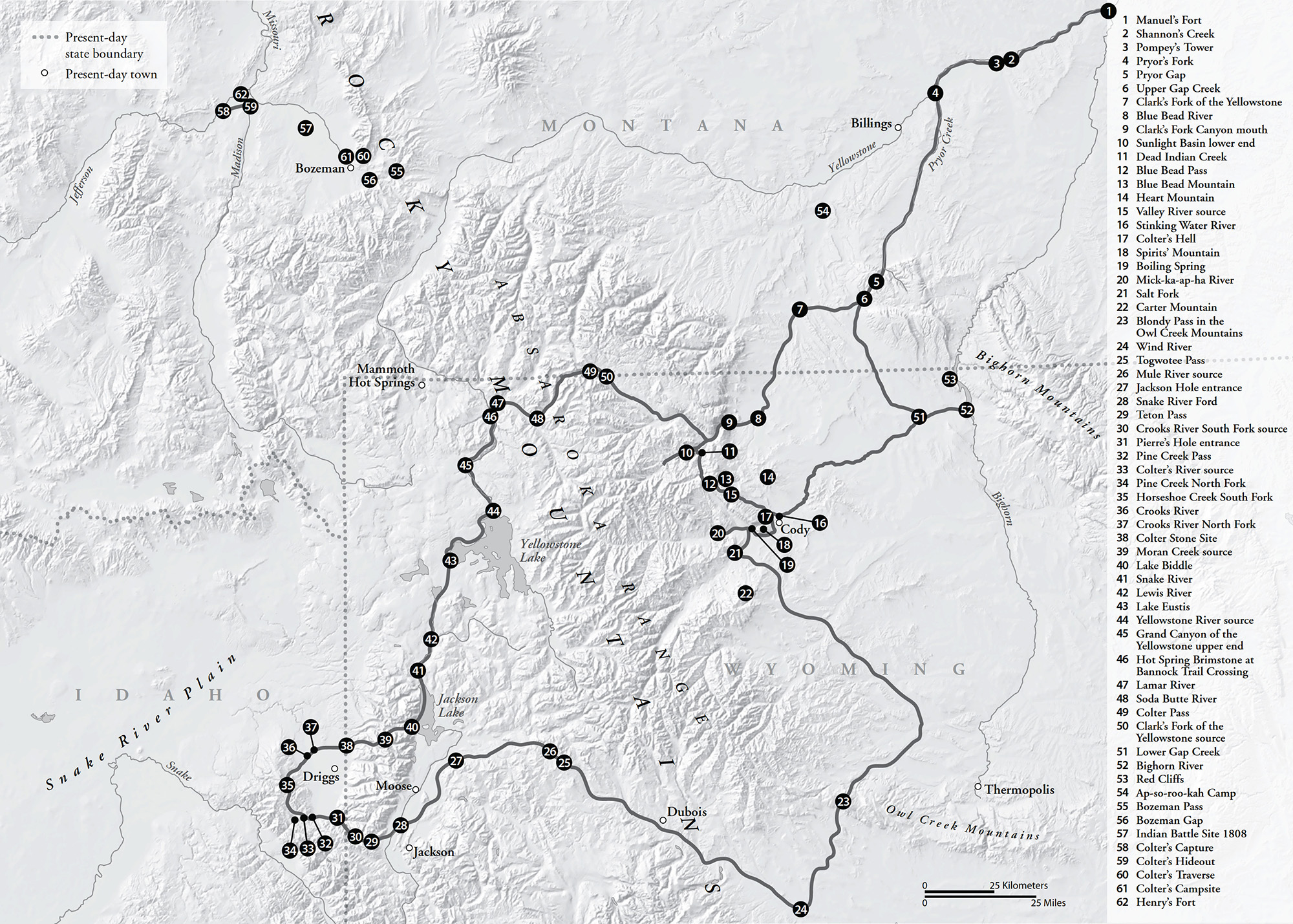

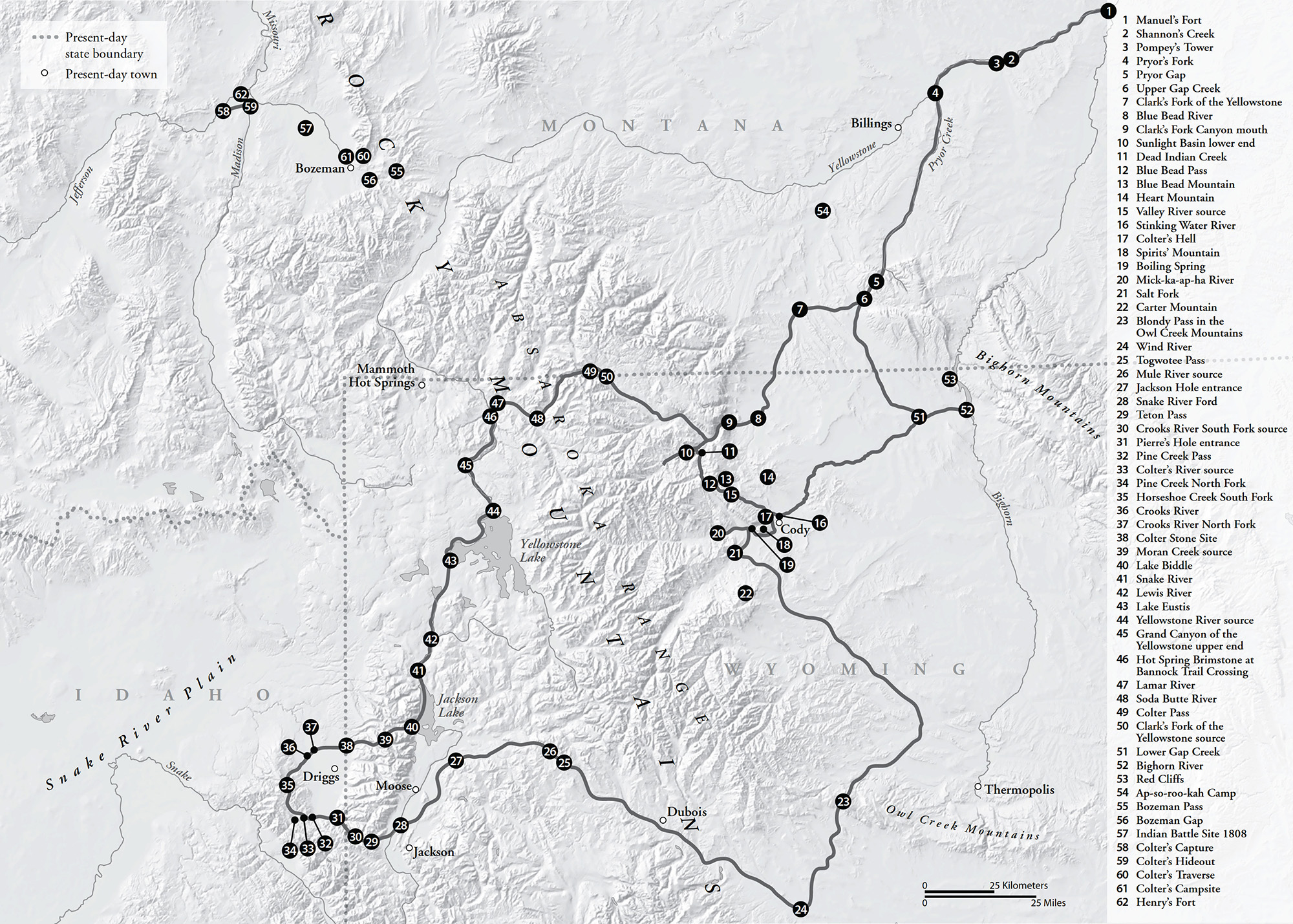

Maps Copyright 2017 by The Countryman Press

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, The Countryman Press,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Lovedog Studio

Production manager: Devon Zahn

Cover art: John Colter Exploring Yellowstone painting by Gerry Metz

The Countryman Press

www.countrymanpress.com

A division of W. W. Norton & Company

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

for Vicki

CONTENTS

IN 1804, JOHN COLTER SET OUT WITH MERIWETHER Lewis and William Clark on the first US expedition to traverse the North American continent. During the twenty-eight-month ordeal, Colter served as a hunter and scout, and honed his survival skills on the western frontier. As the expedition returned and his companions pushed eagerly homeward, he chose to remain in the northern plains and Rocky Mountains. Alone and on foot, Colter discovered unexplored regions, including the majestic Tetons and Yellowstone country.

As he trekked through dangerous and unfamiliar territory, he became a trusted friend to several Indian nations and a foe to another. Some tribes taught him native lore and helped him survive, while a rival tribe declared him a mortal enemy. The tales of his daring adventures and chilling escapes remain unsurpassed.

Colter was the first of the mountain men, acclaimed by the frontiersmen of his time as a living hero. After his death, he became a legend to the explorers, trappers, cavalrymen, and cowboys who followed in his wake. He was the prototype of the ideal Westernerruggedly independent, self-sufficient, and quietly confident in his abilities. Colter grabbed the American imagination in his own time and maintains his hold to this day.

HISTORY IS A STORYA NARRATIVE INTERPRETATION of the past built upon a collection of verifiable facts. Some historical studies contain a substantial core of hard facts. Others have fewer at their disposal and rely more on interpretation. The story of John Colter fits the latter description. Information on the subject is sparse, and Colter himself left no written records.

Accounts of his life exist in a handful of primary documents bequeathed to us by those who knew him. These include the journals of the Corps of Discovery (the Lewis and Clark Expedition); the writings of Thomas James, John Bradbury, Doctor Thomas, and Henry Brackenridge; and a map drawn by William Clark that marks Colters route of 18078. Secondary writings based on these accounts have appeared since Colters time. Some have come from authors of caliber like Washington Irving. Beyond these sources, many aspects of Colters life may be surmised from information left by men like him who scouted and explored, trapped and traded, traveled and survived in the same wilderness in the same era. These primary and secondary accounts are liberally quoted in the following text in order to provide the reader with original documentation and an authentic feel for frontier thought and expression.

In addition to written sources, information can be gained by retracing Colters stepsseeing what he saw, hearing what he heard, and experiencing firsthand how he and his contemporaries survived in the wildernesshow they pitched a shelter, built a fire, followed a trail, and forded a stream. Chapter Four offers an interpretation of Colters 18078 winter trek based on this kind of careful, on-site investigation of the entire route, in collaboration with cited historical, archaeological, and cartographic evidence.

Reconstructing Colters movements based partially upon secondary evidence is acceptable in this context. Like scientific theory, such an endeavor involves using informed interpretation to prompt further investigation. The result is an accumulation of knowledge on the subject and a steady movement toward verification. In this case, it is important to refrain from claiming the final word on the subject. Further thought and study are encouraged. Substantial endnotes are provided for this purpose.

In addition to firsthand and secondary evidence, other information existsapocryphal information that envelops every legendary person like a fog, obscuring the story. This makes the task of creating a valid interpretation all the more difficultand important. While searching for every available scrap of useful information, the researcher must dismiss many sources. Those sources deemed valid and pertinent to the study of John Colter appear in Works Cited.

MOUNTAIN MAN

THE MISSOURI RIVER MEANDERS THREE THOUSAND miles across the interior of North America. It begins as snowmelt in the lofty peaks of the Rocky Mountains and trickles into rivulets that converge to form the river. From there, the Missouri follows its ancient path through arid foothills and windswept prairies.

As the river flows eastward, the climate grows wetter and other streams join the course. At last it enters dark green stretches of humid forest. In the midst of this riparian lushness, only seventy-six miles from the end of its course, the Missouri passes a shady bluff on the south bank, upstream from a tiny village called La Charette.

Before settlement arrived, nature had dominion over the surrounding woodlands. Wildlife ruled the forest floor and birds abounded in the leafy canopy. Interruptions to the serenity came only from an occasional clap of thunder or crash of a falling tree.

On an overcast day in May 1804, a strange sound rose from below the bluff. A party of men rounded the bend, struggling and cursing their way upstream against a current made heavy by snowmelt and spring showersand made treacherous by driftwood and snags. They groaned aloud in English and French as they tugged on keelboat towlines and paddled their pirogues upriver.

These frontiersmen and voyageurs understood the contrary habits of waterways. They had received excellent educations along the river roads of the East. They could read ripples and rapids. They recognized woodland plants and animals. They knew how to hunt them for sustenance and shelter, and they kept a keen eye on the abundance around them.

One man among them observed the land with more than passing interest. In the thick timbers and fertile bottomlands he saw a potential home. His companions called him Colter. Formal records gave his first name as John. Tradition says he was born about 1774 in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Britain controlled the colonies then and prohibited settlement westward. But the frontier families, with their restless ways, felt confined by a boundary line impulsively scrawled on a map. Many chose to ignore the rules of a distant, disinterested monarch.

Next page