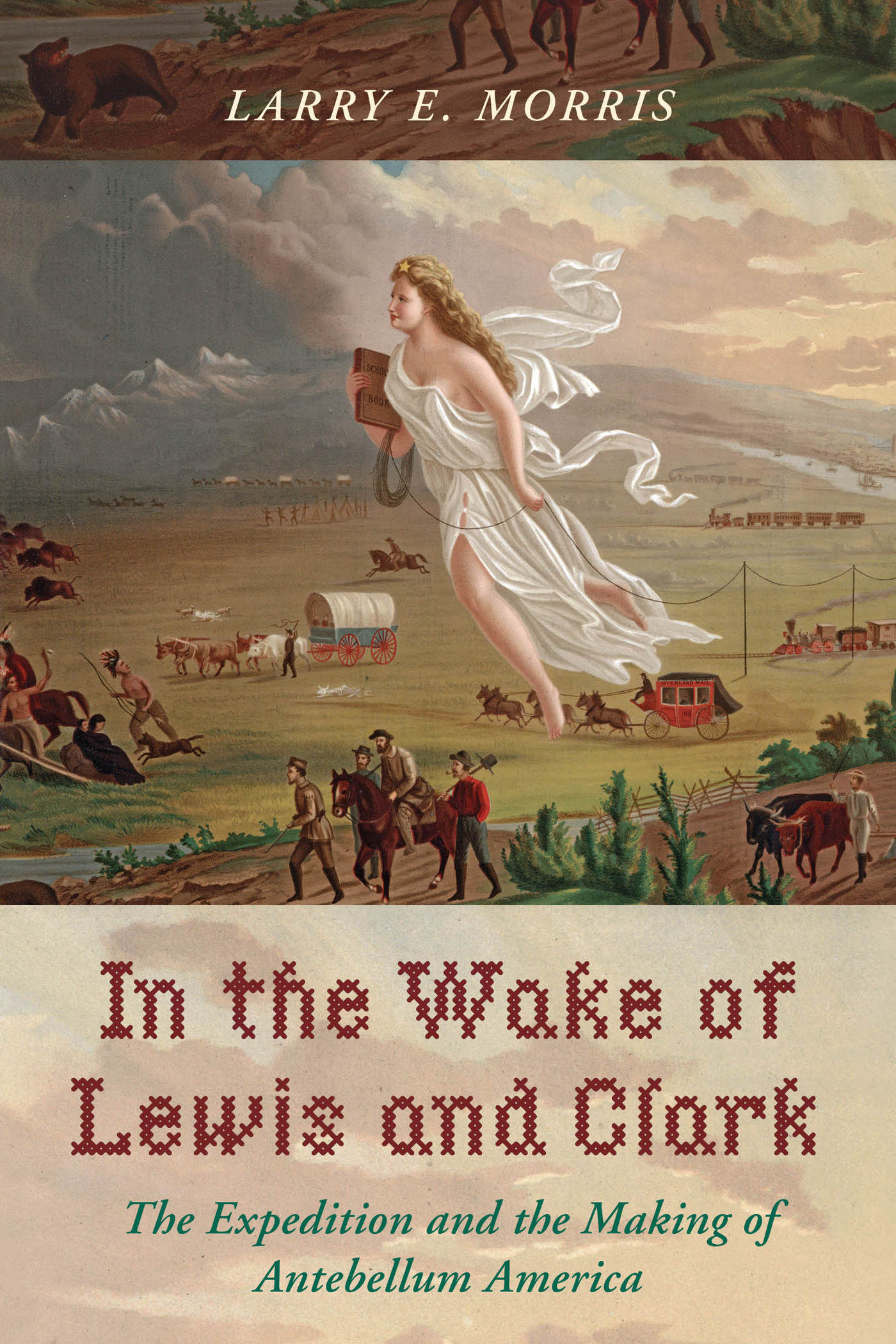

In the Wake of

Lewis and Clark

In the Wake of

Lewis and Clark

The Expedition and the Making of Antebellum America

Larry E. Morris

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2019 by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Morris, Larry E., 1951 author.

Title: In the wake of Lewis and Clark : the expedition and the making of antebellum America / Larry E. Morris.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018030652 (print) | LCCN 2018045043 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442266117 (electronic) | ISBN 9781442266100 | ISBN 9781442266100 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Lewis and Clark Expedition (18041806) | West (U.S.)Discovery and exploration. | United StatesHistory17831815. | United StatesHistory18151861.

Classification: LCC F592.7 (ebook) | LCC F592.7 .M686 2019 (print) | DDC 917.804/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018030652

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Thus the Seer,

With vision clear,

Sees forms appear and disappear,

In the perpetual round of strange,

Mysterious change

From birth to death, from death to birth,

From earth to heaven, from heaven to earth;

Till glimpses more sublime

Of things, unseen before,

Unto his wondering eyes reveal

The Universe, as an immeasurable wheel

Turning forevermore

In the rapid and rushing river of Time.

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow,

Rain in Summer, 1845

Introduction

On Sunday, June 29, 1806, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their party of twenty-nine men, one woman, and one child pursued the hights of the ridge on which [they] had been passing for several days and, five miles farther on, decended from [the] ridge [and] bid adieu to the snow. Later called Lolo Pass, at the present Idaho-Montana border, this was hardly foreign territory to the captainsthey had followed the same Indian trail in the opposite direction the previous September. So it was not by accident that after a supper of venison, they continued [their] march seven miles further to the warm springs.

The principal hot spring was about the temperature of the warmest baths used at the hot springs in Virginia, wrote Lewis, who spent nineteen minutes in the water but only with difficulty. Then he looked on as both the men and indians amused themseves with the use of a bath. After staying in the hot pool as long as they could bear it, the Indians ran and plunged themselves into the creek the water of which is now as cold as ice can make it; after remaining here a few minutes they returned again to the warm bath, repeating this transition several times but always ending with the warm bath.

The next day, a little before sunset, they arrived at their old encampment on the south side of the creek a little above its entrance into Clarks river. This was the Travelers Rest camp of September 911, 1805, just south of present Lolo, Montana (twelve miles south-southwest of Missoula).

Deer were plentiful in the area, and over the next few days the hunters brought in a good supply of venison. Others in the party packed supplies and repaired guns while the horses got a well-deserved rest. There was even time for some of the men to run footraces against the hardy strong athletic Indians, the sole annoyance being the musquetoes, which were excessively troublesome. By July 2, Lewis and Clark and their band of explorers were ready to depart the next day with ambitious plans to split into five different groups and explore a good deal of present Montana. That peaceful night, as he had done on many nights, Lewis recorded botanical details in his journal, noting that the wild rose, servise berry, white berryed honeysuckle, seven bark, elder, alder aspin, choke cherry and the broad and narrow leafed willow are natives of this valley.

In many ways, that July day was the last normal day of the expedition for the captains, the last time they were both in good health and traveling together, the last time Clark would draw on Lewiss journal entry to write his own, the last day of traveling together that neither of them had seen any Europeans, other than the expedition members, since departing Fort Mandan.

Forty days and more than six hundred miles later, on August 12, the various troops of the Corps of Discovery reunited in present North Dakota, just above the confluence of the Missouri and Little Missouri Rivers. At meridian Capt Lewis hove in Sight with the party which went by way of the Missouri as well as that which accompanied him from Travelllers rest, wrote Clark. The joy of the reunion, however, was quickly tempered: I was alarmed on the landing of the Canoes, continued Clark, to be informed that Capt. Lewis was wounded by accident. I found him lying in the Perogue.

Although on July 27 Lewis, George Drouillard, and the Field brothers had escaped unharmedbut had killed two Blackfoot Indiansin the sole violent encounter of the entire expedition, on August 11, Lewis had been accidentally shot by boatman and fiddler (and one-eyed) Pierre Cruzatte as the two were hunting elk. As wrighting in my present situation is extremely painfull to me I shall desist untill I recover and leave to my frind Capt. C. the continuation of our journal, Lewis wrote on August 12. It was his final entry.

Just as Lewiss gunshot wound and his leaving the journals to Clark were portents of things to come, the captains first meeting with Europeans was likewise a signal of the future. At 8 A. M. the bowsman informed me that there was a canoe and a camp he believed of whitemen on the N. E. shore, Lewis had also recorded on August 12. I directed the peroque and canoes to come too at this place. Lewis found two hunters from the Illinois by name Joseph Dickson and Forrest Hancock. these men informed me that Capt. C. had passed them about noon the day before. Dickson and Hancock had ascended the Missouri in the summer of 1804, just weeks after Lewis and Clark, and had been hunting and trapping beaver for two years, the first of a host of frontiersmen the captains would meet over the next six weeks, all of them going upriver before learning of the corps successful return.

Clearly, Lewis and Clark can hardly be credited with igniting this trapping frenzyespecially since rumors abounded the same summer that the entire Corps of Discovery had been lost or slaughtered by Indiansbut John Colters going westward with Dickson and Hancock, with Clarks enthusiastic approval, was another sign, this one a harbinger that Lewis and Clark veterans would play key roles in the most successful trading and exploration ventures, with an unbroken line leading from Lewis and Clark, Manuel Lisa, Andrew Henry, and William Ashley to Jedediah Smith, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Kit Carson, and John C. Frmont.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.