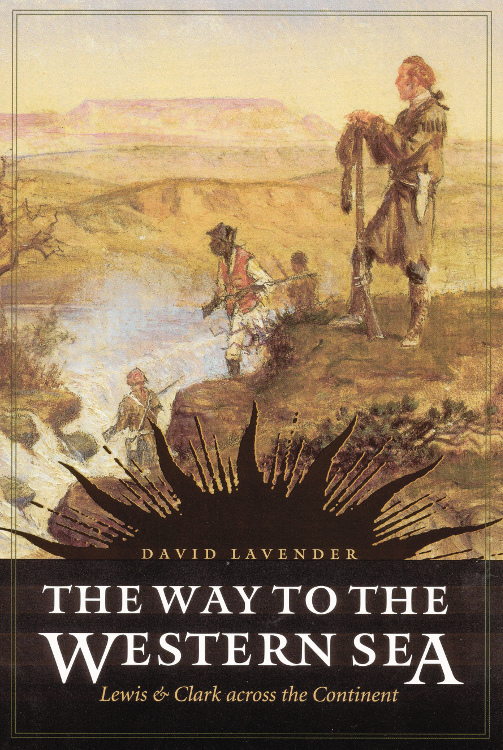

The Way to the Western Sea

LEWIS AND CLARK ACROSS THE CONTINENT

DAVID LAVENDER

University of Nebraska Press

Lincoln and London

1998 by David Lavender

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lavender, David Sievert, 1910

The way to the western sea: Lewis and Clark across the continent/David Lavender.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Harper & Row, c1988.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN: 978-0-8032-8003-8

1. Lewis and Clark Expedition (18041806) 2. Lewis, Meriwether, 1774-1809. 3. Clark, William, 1770-1838. 4. West (U.S.)Discovery and exploration. 5. West (U.S.)Description and travel. I. Title.

F592.7.L38 2001

917.804'2dc21 2001033592

To M. M. L.

Always gallant, no matter how hard the way

Contents

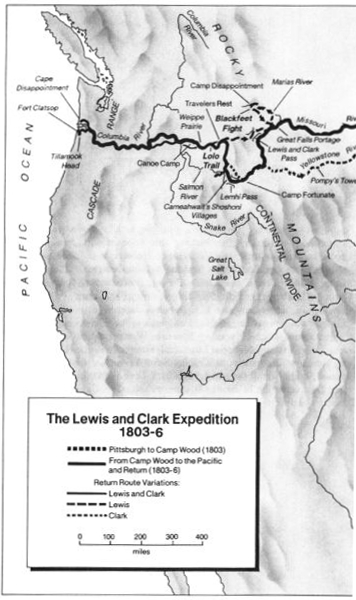

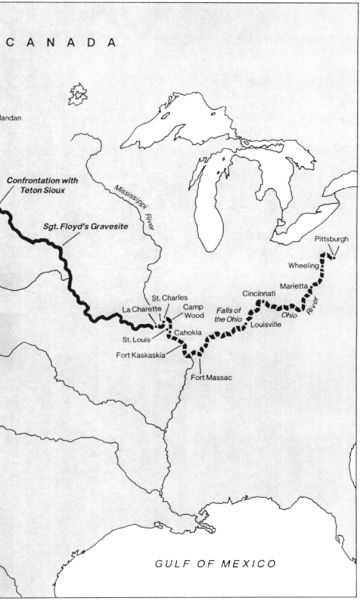

List of Maps

Acknowledgments

In one way or another, the following people, listed alphabetically, contributed significantly to making this book work: Christian Brun, Department of Special Collections, University of California at Santa Barbara; Cort Conley, boatman and outdoorsman of Cambridge, Idaho; Sherm and Claire Ewing, ranchers and fliers of Great Falls, Montana; Howard Foulger, now of St. George, Utah, with whom, when he was a U.S. Forest Ranger, I tramped over much of western Montana; Eugene Gressley, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming; Curtis Johnson of Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon; Mildred Lavender; Denise Miller, librarian, Thacher School, Ojai, California; and Marcia Staigmiller of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Inc., Great Falls, Montana, chapter.

ONE

Beginners Luck

Luck! It began for Captain Meriwether Lewis, paymaster of the First Infantry Regiment, United States Army, when he reached his regimental headquarters in Pittsburgh on March 5, 1801, after a rough trip from Detroit, and found in his mail a letter from Thomas Jefferson, recently elected president of the United States.

His thin, long-nosed face must have shown his mingled delight and astonishment. Jefferson needed a private secretary with unusual qualifications. Your knolege of the Western country, he wrote, of the army and of all its interests and relations have rendered it desirable for public as well as private purposes that you should be engaged in that office.

Pay would be five hundred dollars a year. Not much even then, but Lewis could retain his rank as job insurance and save living expenses as a member of the presidents household. Now, that was exciting! Lewis, who was given to quick exhilarations and, balancing them, occasional deep depressions, dashed off a boastful note to an army friendhe would now be in a position to inform you of the most important political occurrences of our government or such of them as I may feel myself at liberty to giveand then wrote a more circumspect letter to Jefferson accepting the appointment. After settling his accounts, he requisitioned three fresh horses, one for riding and two for packing, and shortly after March 10 started for the new federal city of Washington. It was a miserable trip. Flat gray skies, leafless trees, the plop-suck, plop-suck of hooves in the thawing mire, followed by long nights in dreary wayside inns.

Some of the phrases in Jeffersons letter kept returning to puzzle him. Knowledge of the Western country, of the army and all its interests and relations... He knew army procedures and could get along in the wilderness, but surely there was nothing in that to command national interest. Indian affairs? Hardly. The tribes of the Northwest had been quiet since their crushing defeat at Fallen Timbers in 1794 by General Anthony Wayne. Military defense? That seemed just as unlikely. British fur traders were no longer occupying posts on American soil and stirring up trouble. Another tension had ended in 1795 when Spain had opened the Mississippi to the flatboats of the pioneers surging across the Allegheny Mountains. The undeclared naval war with revolutionary France was winding down. Peace, in short, seemed assured for many years.

Yet Jefferson wanted his special talents. Strange, strange. Well, hed learn eventually. On he plodded, losing still more time because one of his horses went lame.

He reached Washington shortly after April 1, to find that Jefferson had departed for a short rest at his home, Monticello, in Albemarle County, Virginia. He had left behind, in the leaky, unfinished hull of the Presidents House (now called the White House), a steward, a housekeeper, and three servants whose chief responsibility, until Jefferson returned, would be taking care of Meriwether Lewis. Gratifying enough after a winter on the Northern frontier. Yet probably Lewis would rather have gone south, too, for Albemarle County was home to him as well as to the president.

The Lewis plantation, Locust Hill, named for the big locust trees that sheltered the main buildings, was only eight or nine miles from Monticello. Meriwether had been born there August 18, 1774, the second child and first son of William and Lucy Meriwether Lewis. He scarcely remembered his father, for William Lewis, a lieutenant in the Continental Army, had died in November 1779 from injuries and exposure suffered when his horse fell in an icy stream while he was homeward bound on leave.

The death left Lucy with three small children to raise, a thousand-acre plantation to manage, additional lands in the wilderness to fret about, and sharp worries over British raiders in the vicinity. She solved the problems in part by marrying, six months after her husbands death, another army officer and a man she had known for some time, Captain John Marks. By him she bore two more children.

In 1784 a friend of Markss persuaded him and his family to join a speculative land rush to the Broad River in the wilds of northern Georgia. There is no direct evidence that young Meriwether did not get along with the stepfather who had twice changed his life. Still, he became, during those years, a moody lad who often went alone into the woods with his dogs, frequently at night to hunt raccoons and opossums. He had an eye for plants and one way or another taught himself a good deal about the vegetation he encountered. His mother probably encouraged him. She was a noted herb doctor, and it is not hard to imagine them going into the forest together on collecting trips.

Almost certainly Lucy Marks taught her children the rudiments of writing, reading, and doing sums. Within three years, however, Meriwether had surpassed his mothers capabilities and those of the neighborhood schools. Whether at her urging or his, he was sent back to Locust Hill in 1787. For a little more than two years he attended a sequence of schools run by impoverished divines. The uncles who were acting as his guardians then set him to work on the plantation at the age of fifteen or so. It was an exacting practical educationlearning to oversee the slaves who performed the labor in the almost self-sufficient plantation. Herding, butchering, milling, planting; spinning thread and making clothes; erecting buildings and fences; extemporizing repairs, hauling. Setting up goals and schedules. Keeping accounts. Learning the jargon of the neighboring planters who stopped by to trade news.

Next page