Bison Books editions by David Lavender

Bents Fort

The Fist in the Wilderness

One Mans West

Westward Vision: The Story of the Oregon Trail

CALIFORNIA

LAND OF NEW BEGINNINGS

DAVID LAVENDER

Afterword by the Author

University of Nebraska Press

Lincoln and London

Copyright 1972 by David Lavender

Afterword copyright 1987 by the University of Nebraska Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lavender, David Sievert, 1910

California, land of new beginnings.

Reprint. Originally published: New York: Harper & Row, 1972.

Bibliography: p.

1. CaliforniaHistory. I. Title.

F861.L38 1987 979.4 86-30929

ISBN 0-8032-2874-0

ISBN 0-8032-7924-8 (pbk.)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-7924-7 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-5319-3 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-5320-9 (electronic: mobi)

Reprinted by arrangement with David Lavender

For Mildred, with love

CONTENTS

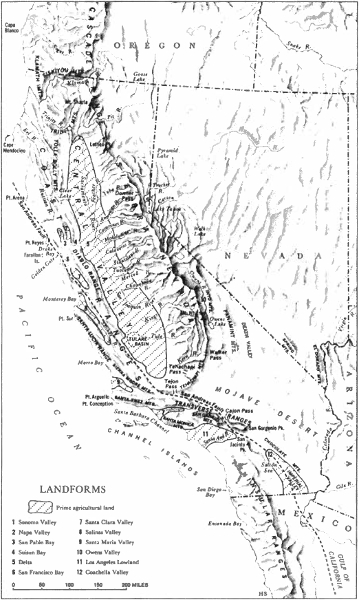

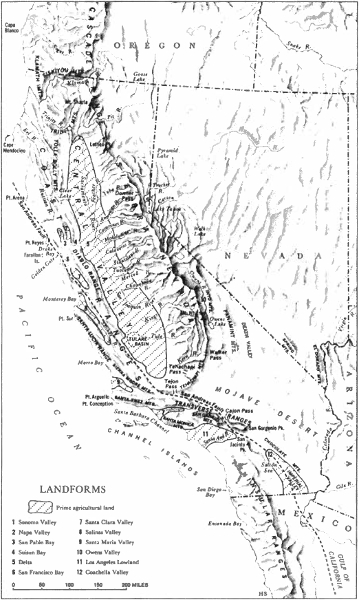

Maps

Prologue to Giganticism

Patterns of Irony

About six miles west of downtown Los Angeles is an accidental juxtaposition of landmarks, natural and man-made, that serves as an ironic introduction to some of Californias furious ambivalences. The site is Hancock Park. Within the parks modest thirty-two acres are several ugly black bogs, a few life-sized, fiberglass replicas of prehistoric mammals, and a cluster of three spectacular buildings that were opened in March, 1965, as housing for the Los Angeles County Art Museum. Fronting both the bogs and the buildings is the nervous energy of Wilshire Boulevard, created during the 1920s to exploit the revolutionary shopping and living patterns just then being created by the automobile.

All tour guides of the city mention these items in isolation. More might be learned by pulling them together.

First, the black bogs. Fenced off by heavy gray wire from the publics careless feet but not from the publics litter, they are a family of odorous petroleum seeps known as the La Brea Tar Pits. Many similar upwellings were once active throughout Southern California, and a few still remain. As their viscous liquid oozed down the hillsides or collected in depressions, as at Hancock Park, the volatile components evaporated. The residue was, and is, a sticky black pitch.

For centuries the pitch served as a useful resource for humans. By daubing it onto their reed baskets and letting it harden, Indians achieved watertight utensils. They used it as a binding material when adding patterns of colored seashells to various objects. Canoes caulked with the pitch could be paddled across twenty or more miles of open ocean to the islands of the Santa Barbara Channel.

The original settlers of Los Angeles also learned to utilize the stuff, hauling congealed chunks into their pueblo, or town, softening it in cauldrons, and smearing it as waterproofing onto the earthen roofs of their square adobe houses. It was a mixed blessing up there, however. Under a hot sun the tar liquefied and dripped in gooey stringers over the eaves onto passers-by careless enough to walk beneath.

But men are curious as well as pragmatic. In 1792, eleven years after the founding of Los Angeles, a visiting scientist, Jos Longinos Martnez, heard stories that led him to ride to the pits in search of nothing more tangible than information. Rain drainage, he had been told, collected on the shiny surface of the depressions, and when other sources of water dried up, the sheen of the liquid was fatally tempting to thirsty wildlife. True enough, Martnez found. In hot weather animals have been seen to sink in it [the lake] and when they tried to escape they were unable to do so, because their feet were stuck and the lake swallowed them. After many years their bones have come up through the holes, as if petrified.

He collected several specimens, but the earth sciences were not far enough advanced in 1792 for him to realize how very old and petrified the bones really were. Another century passed before the La Brea Tar Pits were heralded as one of the stupendous paleontological treasure houses of the world.

For perhaps 40,000 years a succession of mammals (but no dinosaurs or other reptilians) had walked into that deceptive ooze, had bellowed their fright as it engulfed them, and had perished. Condors and great wolves came to feast on the carrion and were caught in their turn. Flesh gone, their bones sank with the others, to be preserved in the airless vaults of bitumen. Recovered, they have provided scientists with a panorama of endless changes in climate and of life adapting itself to the altering weather. There have been saber-toothed tigers and woolly mammoths, inured to cold; tapirs that throve in hot and humid swamps; desert peccaries, tall storks, a peacock; and primitive horses from herds that once ranged the grasslands of the entire continent and then vanished.

There were also human hunters among those mammals. In 1971, a fragment of skull from the pits was tentatively dated as being 23,000 years old. Its belated appearance there in the ooze represents a profound new spirit in the life flow. One manifestation of it later led Jos Martnez to reach gingerly out into the black gum for petrified bones that he could take home and study. Still later, the warmth of that same strange inner fire prompted the building of the nearby art museum, its slender colonnades rising beside those ancient pools of darkness like cords of solidified airone of the most magnificent buildings, declared historian T. H. Watkins of Oakland, an area not given to hyperbole about Los Angeles, ever achieved by any civilization anywhere at any time.

And from out front comes the surging roar of Wilshire Boulevard. Opposing phalanxes of automobiles stream and stop, stream and stop, their motors agitated by complex refinements of the same substance that preserved, in the La Brea Pits, those petrified relics of vanished forms of life. It was on Wilshire Boulevard, one remembers idly, that synchronized traffic lights were used for the first time anywhere by any civilization. That, too, is a manifestation of the human spirit, making, like art, still another declaration of imposed order. And the cars stream and stop, stream and stop, and there are days when the huge depression known as the Los Angeles Basin is filled almost to its brim with another dark pool of hydrocarbons.

In some distant future will a member of a new species reach out for one of our relics and turn it in his hands, puzzling?

Stored Energy

We knowwithout really knowing, because the scope of the process stuns the imaginationthat this continent, like all continents, has been shaped by incalculable forces working throughout almost incalculable stretches of time. It may even be that time does not exist within so boundless a happening. Still, there were rhythms. Oceans advanced and retreated. Mountains rose, were leveled, and stubbornly rose again. Valleys sank and were filled. One would hardly call it a plan of action. But as an inchoate experiment, a testing of methods... well, anyway, there came to the central section of the state-to-be a certain enduring pattern.

It was a four-part alignment: salt water, then a long mountain range bordered on part of its eastern side by a profound geosyncline, and beyond that depression a still greater line of mountains. Using current terminology and moving from west to east, we have the Pacific Ocean, the Coast Ranges, the Great Central Valley, and the Cascade-Sierra Nevada wall.

Next page