Acknowledgments

This book began over a conversation at a Western History Association meeting in Oakland, California. It has been with us for a while. It has seen our oldest children go off to college and our youngest children develop into promising artists. As we put the final touches on this book, we are both proud, as with our youngest children, of its artistic nature. But, as with our oldest children, we are proud to see it leave the house.

The first person that we need to recognize is our doctoral mentor Albert Hurtado. Both of us worked with Al at the University of Oklahoma, where we wrote dissertations on aspects of California Indian history in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was a great pleasure to work with Al and this book in some ways answers the question he used to ask us, usually in the margin of our seminar papers: what is the story here? His work and guidance showed us that stories can carry great explanatory or analytical power, but they do so better when people show up in them.

Niels Hooper has balanced his enthusiasm for the project with his patience and forbearance. We are grateful for both. We appreciate his faith in what we envisioned. As we came to the end of writing this book and preparing it for production, Robin Manley stepped in and guided us to the finish line.

Several people aided us in researching, developing, and fine-tuning this book. We are especially grateful to the five people who reviewed this manuscript for the University of California Press: Terri Castaneda, Cutcha Risling Baldy, Nicolas Rosenthal, Khal Schneider, and Natale Zappia. They were generous with their time, and their insights have made this a better book. At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Stephen Bohigian, Neil Dodge, and Lee Hanover provided excellent assistance as graduate student research assistants. Willy thanks the students in a California Indian history class at the University of California, Los Angeles, for allowing him to tell some of these stories. That class remains a highlight of his teaching career. At Guilford College, students in Damons writing-intensive California Indian course provided helpful feedback. Our friend and colleague Cheryl Wells gave this book a much-needed and helpful copyedit. We have presented portions of this book at various conferences: the Organization of American Historians, the Historians of the Twentieth Century United States, Western History Association, American Society of Ethnohistory, and Native American and Indigenous Studies Association. Thank you to panel commentators and participants.

At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Annette Amdal worked tirelessly as department administrator. Department chairs Andy Kirk and David Tanenhaus helped provide us with time to write this book. Deans Chris Hudgens, Chris Heavey, Jennifer Keene, and John Tuman helped to fund travel and production costs. Thanks to Raquel Casas, Carlos Dimas, Mark Padoongpatt, Marcie Gallo, Mike Green, Susan Johnson, Todd Robinson A.B. Wilkinson, and Tessa Winkelmann, among others, for making UNLV a vibrant place to teach and research Western and United States history. At Guilford College, faculty research funds supported travel to produce the book, and numerous colleagues provided helpful commentaryin formal presentations or in the hallways. Particular thanks go to Diya Abdo, Phil Slaby, Kathryn Shields, and Bob Williams.

Betty Matthews and Charlotte Bauer always showed up to hear Willy deliver a lecture on California Indian history, whether it was at the Sun House Museum in Ukiah or the California State Indian Museum in Sacramento. Willys grandmothers, Anita Rome and Elizabeth Fritsch, passed away during the writing of this book. They are both deeply missed. His parents, William and Deborah, have never failed to support him in lifes many ventures. This book could not have been written without their love. Kendra, Temerity, and Scout are probably among the happiest to see this book completed. Thank you, again and as always, for your love and support. Perhaps now, we might have more time for an evening at Hanks, a pickup basketball game, or a Star Wars marathon.

Damons kids, Hollis and Reuben, have grown up with the book. Their growth has also helped him write itthey grew it up. They have both helped in ways they cant imagine. His parents, Judy and Winford Akins, have supported him throughout this project. Damons conversations with Colleen Trimble, Byron Hutto, David Rosfeld, and Mandy Taylor-Montoya could fill a book. In some ways, they have here. He is particularly grateful for Colleen, for helping him learn how to see, how to listen, and how to write from that place.

This is a history. There are others, and we are grateful to the California Indians past and present who shared theirs.

INTRODUCTION

Openings

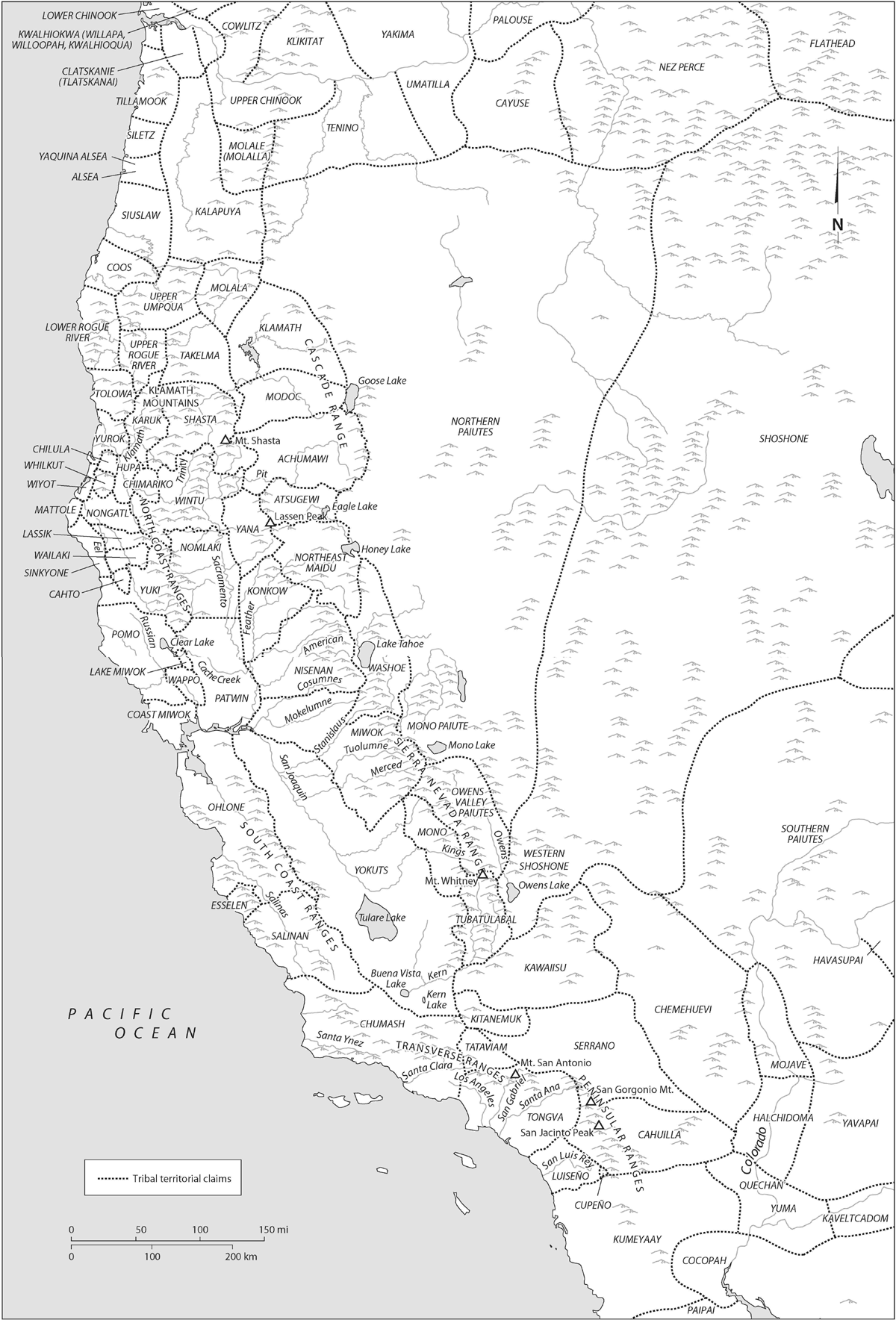

On August 4, 2011, Native and non-Native activists extinguished their sacred fire at Glen Cove, near Vallejo, California. Three months earlier, the land protectors built the fire to protest the city of Vallejos proposal to bulldoze a burial site, which Ohlones call Sogorea Te, to make way for a city park. When the land protectors put out the fire, they marked the end of a long but successful campaign to claim Ohlone lands in the Bay Area. For twelve years, Bay Area Natives and their allies resisted the city of Vallejos proposal to develop the land. When city officials finally decided to consult California Indians, they contacted the Yocha Dehe Wintun Nation and Cortina Indian Rancheria, whom the Native American Heritage Commission of California identified as the most likely descendants of those interred at Glen Cove. City officials did not reach out to Ohlones, who have lived in the Bay Area since their creation, in part because the Ohlones are not a federally recognized tribe, as the Yocha Dehe and Cortina Bands are. In April of 2011, Vallejo city officials announced their intention to go ahead with plans to build a public park, with a parking lot, restrooms, picnic tables, and paved walking trails. Chochenyo and Karkin Ohlone Corrina Gould led scores of Native and non-Native People to occupy Glen Cove and prevent the city from building the park. The land protectors sacred fire burned at the center of tents and two tepees. Dozens of people kept up the vigil to protect the land and Ohlone ancestors. Sogorea Te is one of the last burial grounds still on open land where we can actually touch our feet to the ground and say our prayers the way were supposed to and pass that teaching on to the next generation, Gould said (see fig. 1). Protectors set up tables laden with food, sat down on the earth, and enjoyed one anothers company. After nearly one hundred days of occupying the site, the Yocha Dehe and Cortina Bands brokered a deal between the protectors and the city of Vallejo. The three parties agreed to a cultural easement, like a cultural right-of-way, that guarantees Yocha Dehe and Cortina Bands joint governance over the burial sites without transferring ownership. Protectors celebrated guarding one of the last visible burial sites in the Bay Area.