Buffalo Bill Never Missed and Never Will

Buffalo Bill rode his speedy horse toward a herd of buffalo. With careful aim, he dropped a buffalo with one shot. Before the day ended, he had bagged ten more. In less than eighteen months, he had killed thousands. His nickname spread quickly throughout the Wild West. Buffalo Bill had many jobsPony Express rider, scout, soldier, buffalo hunter. But he was most famous for entertaining audiences with his Wild West show. Many Americans and others around the world could not travel to see the real Wild West, so Buffalo Bill brought it to them.

About the Author

William R. Sanford and Carl R. Green are the authors of more than one hundred books for young people. They bring over sixty years of teaching experience to the many projects they have created.

This book tells the true story of William F. Cody. Most people know him by his famous nickname, Buffalo Bill. He was one of the Wild Wests greatest heroes. He was a brave and resourceful scout, a buffalo hunter, and a distinguished showman. During his lifetime, he was the subject of hundreds of dime novels. In more recent years, he has been brought to life in dozens of films and television productions. You may doubt that one man could pack so much adventure into a single lifetime. If so, rest easy. All of the events described in this book actually happened.

Fourteen-year-old Bill Cody crouched low as his horse galloped across Wyoming Territory. Like all Pony Express riders, he was paid to cover fifteen miles an hour. Horse Creek Station lay a mile behind the young mail carrier. A fresh horse waited for him at Sweetwater Bridge.

Bills horse thundered through a ravine. Without warning, a band of American Indian warriors swarmed down the sides of the ravine. Rifles barked. Bullets whistled past Bills head. The boy flattened himself on the horses back. Reaching for more speed, he put spurs and whip to his mount. Luckily, he was riding one of the stations fastest horses.

With his pursuers two miles behind, Bill pulled up at Sweetwater Bridge. Instead of a fresh horse, he found a dead station keeper. The corral was empty. Bill pushed his tired horse on to Plants Station. A change of mounts was waiting for him. I finished the trip without any further adventure, he wrote later.

Bill rode for the firm of Russell, Majors, and Waddell. He was one of eighty riders who carried the mail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California. The old mail route had curved southward through Texas and Arizona. Letters sent by that route took twenty-five days to reach San Francisco. The Pony Express cut delivery time to ten days. The riders galloped across prairie, desert, and mountains.

Wagon master George Chrisman gave Bill his first job with the Pony Express. The boy assured his boss that he had been raised in the saddle. As a test, Chrisman assigned Bill to a short forty-five-mile leg out of Julesburg, Colorado. Bill proved his worth by finishing the rugged ride on time. His light weight, he said, was easy on the horses. Some months later, stage agent Alf Slade took a liking to the boy. Slade put Bill on the seventy-six-mile leg from Red Buttes to Three Crossings, Wyoming.

Like all the riders, Bill carried mail in pouches sewn into a sheet of leather. This mochila was cut to fit over the saddles wooden frame. As Bill sped into a station, he pulled the mochila out from under him. After a quick dismount, he threw it onto a waiting horse. A station agent scribbled on his time card. A moment later, Bill was off again.

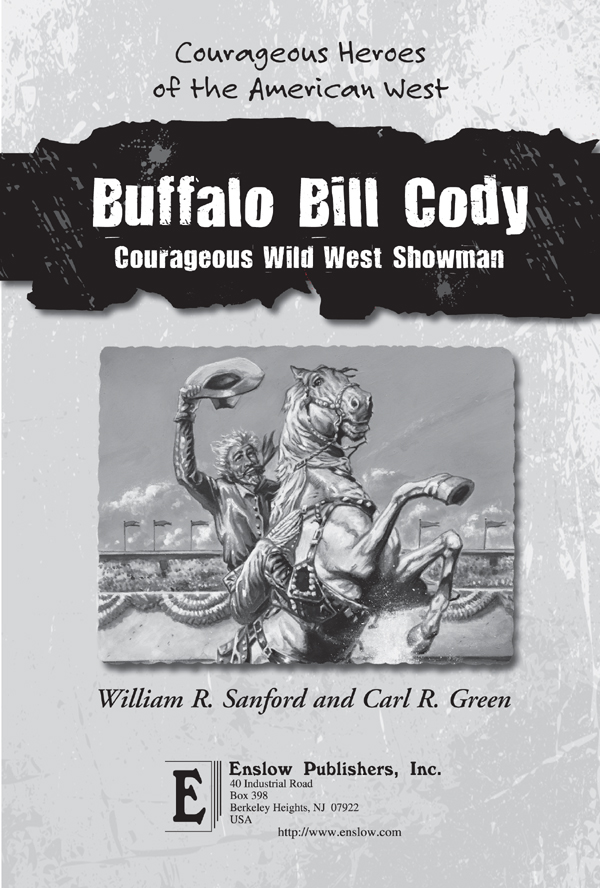

Image Credit: Garlow Collection

Buffalo Bill was only fourteen years old when he became a Pony Express rider. To keep his schedule, he would some-times ride seventy-five miles or more a day. Bill was nine-teen when he posed for this photo.

Bone-jarring rides of seventy-six miles were all in a days work. Bill earned Slades praise with a greater show of endurance. On reaching Three Crossings one day, he found that the relief rider had been killed in a brawl. Bill jumped on a fresh horse and set out for Rocky Ridge, eighty-five miles away. There he picked up the eastbound mochila and retraced his route. The round trip totaled 322 miles. My boy, Slade told him, youre a brick, and no mistake. That was a good run you made. Coming from a tough boss like Slade, that was high praise.

In June 1861, Bill left the Pony Express to be with his ailing mother. On October 24, workers finished the first cross-country telegraph line. Sending a message from New York to San Francisco now took only minutes. The Pony Express could not compete. The bankrupt line shut down in November.

Years later, Buffalo Bill brought the Pony Express back to life in his Wild West show. Daring riders helped cheering crowds relive the drama of the horseback mail service. Buffalo Bill knew the Pony Express as well as anyone alive. As the teenage Bill Cody, he had been a Pony Express rider.

Just like many young people of their day, Isaac Cody and Mary Ann Laycock wanted elbow room. In 1840, the newlyweds moved to the Iowa Territory. The young couple built a four-room log cabin near Le Claire. Samuel was born in 1841, Julia in 1843. On February 26, 1846, Mary gave birth to William Frederick Cody. Her pet name for the baby was Billy. His brother and sisters called him Willy. As a teenager, the boy set the matter straight. He told people to call him Bill.

Danger was a fact of life on a frontier farm. In 1853, a skittish mare reared up, threw Samuel, and fell back on him. The boy died the next day. To take his wifes mind off her grief, Bills father moved the family to Kansas.

At Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Bill saw his first American Indians. He felt an even greater thrill when he saw soldiers drilling their well-trained horses. Before long, his father gave him a half-wild Indian pony named Prince. Horace Billings, Bills uncle, helped the boy tame his new mount. Horace also taught Bill how to throw a lasso.

For a while, all went well. The Codys built a seven-room log cabin at Salt Creek Valley. Isaac won a contract to supply hay to Fort Leavenworth.

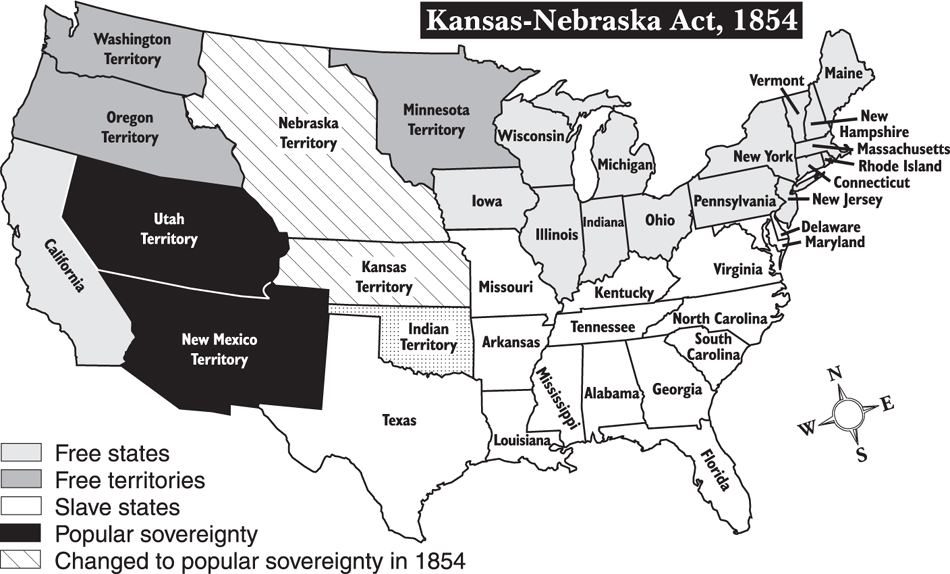

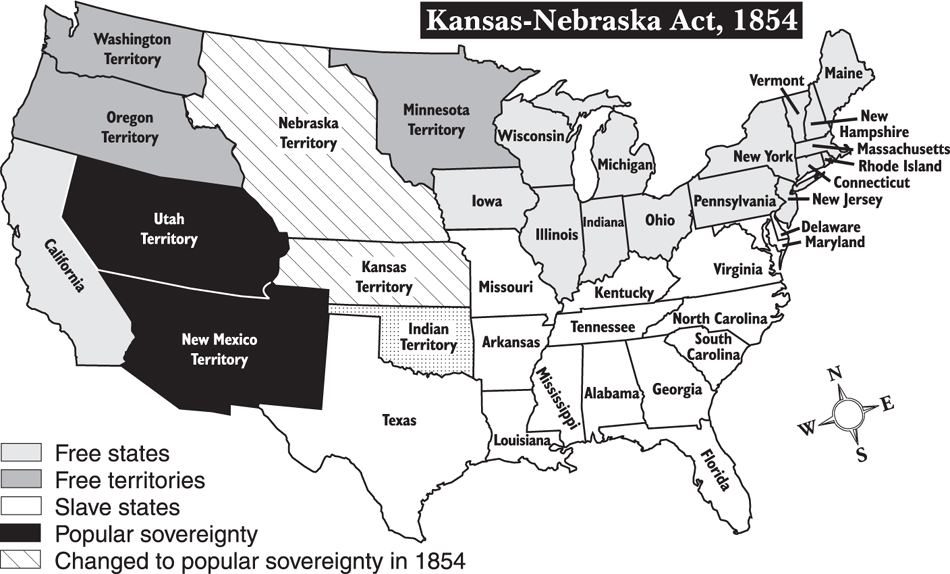

In May 1854, Congress passed a law that touched off years of strife. The law gave Kansas the right to choose to be a free state or a slave state. That set off a race to settle the territory. Proslavers and antislavers hurried to stake their claims.

That September, Bill and his father passed a proslavery rally. The leaders stopped Isaac and forced him to speak to the crowd. His father, Bill wrote later, said he opposed the spread of slavery. That was too much for one proslave hothead. The man stabbed Isaac in the chest. Eight-year-old Bill helped carry his father to the nearby trading post.

Isaac survived, but bands of proslavers were hunting for him. He went into hiding. Unable to find their man, the raiders stole the Codys livestock and burned their hay. But their anger did not stop there. Bill and his sisters had been going to a country school. The teacher fled when angry proslavers threatened to burn the school to the ground.

Image Credit: Enslow Publishers, Inc.

The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act had a dramatic impact on Bills family. The proslavers who flooded into Kansas often attacked anyone who held abolitionist beliefsa group that included Bills father, Isaac. This map shows the affect of the Kansas-Nebraska Act on the United States.