Also by Richard A. Serrano

One of Ours: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing

My Grandfathers Prison: A Story of Death and Deceit in 1940s Kansas City

Last of the Blue and Gray: Old Men, Stolen Glory, and the Mystery That Outlived the Civil War

Text 2016 by Richard A. Serrano

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

This book may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write: Special Markets Department, Smithsonian Books, P.O. Box 37012, MRC 513, Washington, DC 20013.

Published by Smithsonian Books

Director: Carolyn Gleason

Managing Editor: Christina Wiginton

Production Editor: Laura Harger

Editor: Duke Johns

Designer: Nancy Bratton

Map: Bill Nelson

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Serrano, Richard A.

American endurance : Buffalo Bill, the Great Cowboy Race of 1893, and the vanishing Wild West / by Richard A. Serrano.

Description: Washington, DC : Smithsonian Books, 2016. |

Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015047567 | ISBN 9781588345752

Subjects: LCSH: Endurance riding (Horsemanship)West (U.S.)

History19th century. | Horse racingWest (U.S.)History

19th century. | Cross-country (Horsemanship)West (U.S.)

History19th century. | CowboysWest (U.S.)History19th century. |

Buffalo Bill, 18461917. | Worlds Columbian Exposition

(1893 : Chicago, Ill.) | West (U.S.)History18901945.

Classification: LCC SF296.E5 S47 2016 | DDC 798.40978dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015047567

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the works, as listed in the individual captions. Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these images individually or maintain a file of addresses for sources.

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-58834-576-9

v3.1

For Michael, Ben, Elise, and Alexander

My buckaroos

Daring, laughter, endurancethese were what I saw upon the countenances of the cow-boys.

Owen Wister, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains, 1902

Contents

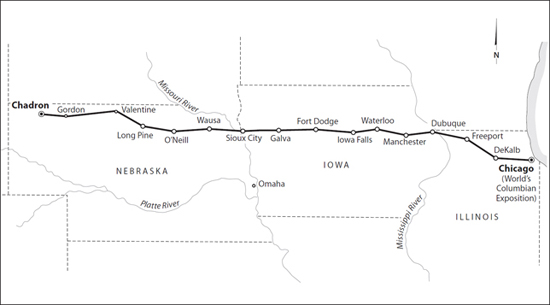

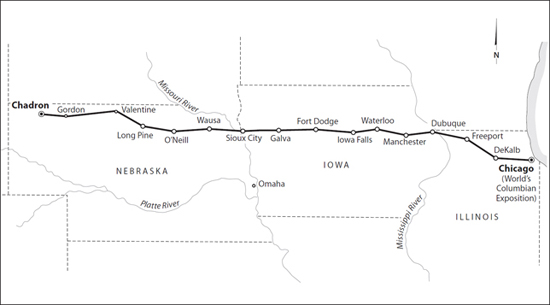

Route of the Great Cowboy Race from Chadron, Nebraska, to Chicago, 1893

The West of Our Imagination | |

Of all the riders in the Great Cowboy Race of 1893, none was better known or more widely feared than the notorious outlaw Doc Middleton. Some cowboys still rode the range and herded cattle; he stole horses. Many more were starting to settle down and raise families; he lived by the gun. He had been hunted for years by sheriffs posses, scrambling along the Niobrara River basin.

He rode through the tiny town of Chadron, Nebraska, several days ahead of the race. In the afternoons, he trotted his horse up and down Second Street, exercising it, keeping the brown gelding lean and limber. The men peered at him from the saloon and shop windows. The ladies dashed outside and plucked strands from the horses tail. Souvenirs, they said; keepsakes.

The race began near dusk on a June afternoon in 1893, with a pistol shot fired from the balcony of the new Blaine Hotel. But Doc at first held back. Under his wide-brimmed hat, his eyes followed the other eight riders as they vanished in a whirl of hooves and dust.

Boys, he told the Chadron crowd, his beard so long it nearly hid his holsters. Im behind now. But I may be ahead. With a cowboy holler, he galloped off.

John Berry rode, too. He normally worked as an engineer and surveyor, and unlike Doc Middleton, he was far from being any wild cowboy. He helped lay the right-of-way for the Fremont, Elkhorn, and Missouri Valley Railroad, pushing one track at a time through the Nebraska Panhandle. He had helped plat the town of Chadron, too. When gossip around town turned serious about a thousand-mile cowboy race from Chadron to Chicago and the Worlds Columbian Exposition, Berry helped map the route.

For that, the Chadron race committee had ordered him disqualified. But Berry rode anywayunder protest. When he reached the finish line at the thousand-mile tree marker at Buffalo Bill Codys Wild West show next to the fair in Chicago, he nearly fell off his horse. He was caked in dust, and his clothes were shredded. I rode the last 150 miles in twenty-four hours, he gasped. Sore? Well, I should say I was. I am so sleepy I cant talk. I have had no sleep for ten days to amount to anything.

For two weeks he had raced his chestnut stallion (named Poison) through the Nebraska Sand Hills, across Iowa cornfields, and into Illinois, often just hoofbeats ahead of county deputies, humane society and animal rights protesters, and two governors who pledged to shut down the race and arrest any rider who abused his horse.

The Great Cowboy Race of 1893 tested a particularly American virtue: endurance. It was launched at the close of the Western frontier and near the start of the twentieth century. Nine men rode leaning over their horses, hats slapping in the wind, defiant symbols of the vanishing Wild West. For two weeks they thundered toward the noisy, crowded, cobblestone metropolis of Chicago and the dazzling White City of the Worlds Columbian Exposition.

In Chicago, cable cars and electric trolleys were fast replacing horses. The exposition was focused on the future, a future that would not include cowboys. It previewed the wonders of the world that was to come, while the West looked back at the cowboy past.

The American frontier was born of adversity; hard times rocked its cradle. The epic push to settle the vast swaths of grassland and uphill country past the Missouri River had taken muscle, courage, and ingenuity. Days filled with hard labor were followed by lonely twilight in dugouts far from families back east or across the broad Atlantic. Isolation shrouded the Plains, and in some locations the threat of Indian attacks lurked over the next ridge.

Yet there persisted an innate drive to break the land and hammer down stakes, to launch rough-and-tumble pop-up towns on either side of the Rockies, to toughen the frontier resolve, and to carry the country into that new and modern American century.

Chadron sprouted up just south of the purple badlands; Wounded Knee lay just a days ride away in southwestern South Dakota. The town was begun near the White River and Chadron Creek. It was founded by an Irish widow named Fannie OLinn. She set up a trading store, got herself appointed postmistress, and brought in a livery stable. The saloons followed her. But when a new railroad line swung six miles out from the OLinn settlement, people simply picked up their homesteads and moved in closer to the new depot. Thus was born the city of Chadron, another fragile Western outpost clinging to survival.