ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

As A HISTORIAN WHO had neither published work related to the history of the frontier nor organized an exhibit, I came to this project in dire need of help. In the ensuing months, I was the beneficiary of more support than I had initially thought necessary and more than I could ever have expected to receive. I certainly never expected that as word of what we were doing spread, I would find on my desk a copy of a supermarket tabloid whose headline reinforced our idea of the frontier as a set of metaphors anyone could inhabit: SPACE ALIENS HELPED INDIANS BEAT CUSTER. This and other, more prosaic, items that we accumulated during the long planning process enhanced my growing realization that the frontier is in fact a ubiquitous presence in American popular culture. Friends who shared my unfamiliarity with frontier historiography also shared this growing realization as they found that promises to watch out for useful stuff had them constantly clipping newspapers and noting what they were seeing in stores, catalogues, and elsewhere in their daily lives. Fortunately, we can now leave this activity to Patricia Limerick, whose essay in this volume suggests the extent to which we only scratched the surface.

The Newberry Library is a small institution by academic standards, with approximately one hundred employees complemented by a remarkably dedicated corps of volunteers. At one point or another virtually every member of the Newberry staff contributed energy and expertise to this project. I cannot overstate the continuing pleasure of working with such energetic, knowledgeable, and humane colleagues. In particular I would like to thank James Akerman, John Aubrey, Dick Bianchi, Richard Brown, Ken Cain, Laura Edwards, Emily Epstein, Fred Hoxie, Ruth Hamilton, Kathryn Johns, Robert Karrow, Harvey Markowitz, Patrick Milton, Joan ten Hoor, David Thackery, Carol Sue Whitehouse, Mary Wyly, and the entire paging staff of special collections.

During the three years of work on this project a number of colleagues have generously contributed time and expertise. Kathleen Neils Conzen, William Cronon, David Gutirrez, Patricia Limerick, Martin Ridge, and Donald Worster constituted a genial but critically insightful advisory board during the planning stage. Among the countless scholars to whom we are grateful for suggestions, Sharon Boswell, Brian Dippie, Paul Fees, and Ramon Price were especially helpful in the identification and location of appropriate images. Karen Kohn's expertise in the winnowing of images and creation of a preliminary design brought two scholars with limited visual skills to the point where we actually could envision how all this might look in a gallery. The exhibit itself was designed by Kent Gay and Cliff Abrams, of Abrams, Teller, Madsen, Inc.

Planning and implementation grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities have been essential, and I am grateful to David Martz for his willingness to provide the kind of candid criticism that one needs to write a decent proposal. Funding has also been provided by AT&T. The Dr. Scholl Foundation has provided resources through its generous support of the Newberry's Dr. William M. Scholl Center for Family and Community History.

Most of the items in this exhibition are in the Newberry Library Collections. We have, however, either borrowed or reproduced materials from a number of institutions. We wish to thank the following for their generosity: Anheuser-Busch Corporate Archives, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Chicago Historical Society, Robert L. Parkinson Library & Research Center at Circus World Museum, Remington Museum, C. M. Russell Museum, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, and Washington University Art Gallery.

This catalogue would not have been possible, at least not in this form, without the enthusiasm, persistence, and good sense of Eileen McWilliam of the University of California Press. I am also grateful to Richard White and Patricia Limerick for writing essays and to the anonymous readers enlisted by the Press for providing criticism and suggestions. Stephanie Fay brought everything together in the final stages, working patiently with a difficult manuscript.

Hilah Geer prepared the catalogue checklist. I had no idea how difficult that task would be; I'm not sure she did either. Nevertheless, she has done it with remarkable care, attention to detail, and good cheer. As registrar for the exhibition she has also been indispensable to its fruition.

This is Richard White's exhibition. Its ideas are his ideas; its insights reflect his scholarship. Richard's patience, energy, good humor, and generosity have contributed mightily to the pleasure I associate with this project. He has also served as a model colleague, teacher, and collaborator.

RICHARD WHITE

FREDERICK JACKSON TURNER

AND BUFFALO BILL

AMERICANS HAVE NEVER had much use for history, but we do like anniversaries. In 1893 Frederick Jackson Turner, who would become the most eminent historian of his generation, was in Chicago to deliver an academic paper at the historical congress convened in conjunction with the Columbian Exposition. The occasion for the exposition was a slightly belated celebration of the four hundredth anniversary of Columbus's arrival in the Western Hemisphere. The paper Turner presented was The Significance of the Frontier in American History.

Although public anniversaries often have educational pretensions, they are primarily popular entertainments; it is the combination of the popular and the educational that makes the figurative meeting of Buffalo Bill and Turner at the Columbian Exposition so suggestive. Chicago celebrated its own progress from frontier beginnings. While Turner gave his academic talk on the frontier, Buffalo Bill played, twice a day, every day, rain or shine, at 63rd StOpposite the World's Fair, before a covered grandstand that could hold eighteen thousand people.

Although Turner, along with the other historians, was invited, he did not attend the Wild West; nor was Buffalo Bill in the audience for Turner's lecture. Nonetheless, their convergence in Chicago was a happy coincidence for historians. The two master narrators of American westerinng had come together at the greatest of American celebrations with compelling stories to tell. The juxtaposition of Turner and Buffalo Bill remains, as Richard Slotkin has fruitfully demonstrated in his Gunfighter Nation, a useful and revealing one for understanding America's frontier myth. The Newberry exhibition juxtaposes Turner and Buffalo Bill for reasons somewhat different from Slotkin's. But like Slotkin the exhibition takes Buffalo Bill Cody as seriously as Frederick Jackson Turner. Cody produced a master narrative of the West as finished and culturally significant as Turner's own.

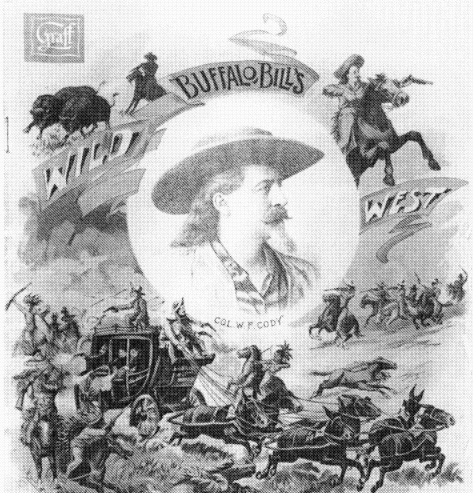

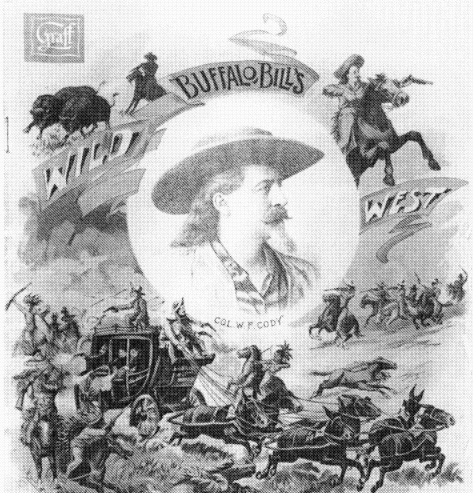

FIGURE 1., Buffalo Bills Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World: Historical Sketches and Programme, Chicago, 1893.

Turner and Buffalo Bill told separate stories; indeed, each contradicted the other in significant ways. Turners history was one of free land, the essentially peaceful occupation of a largely empty continent, and the creation of a unique American identity. Codys Wild West told of violent conquest, of wresting the continent from the American Indian peoples who occupied the land. Although fictional, Buffalo Bills story claimed to represent a history, for like Turner, Buffalo Bill worked with real historical events and real historical figures.

These different stories demanded different lead characters: the true pioneer for Turner was the farmer; for Buffalo Bill, the scout. Turners farmers were peaceful; they overcame a wilderness; Indians figured only peripherally in this story. In Codys story Indians were vital. The scout, a man distinguished by his knowledge of Indians habits and language, familiar with the hunt, and trustworthy in the hour of extremest danger,

Next page