ALSO BY PETER PAGNAMENTA

Sword and Blossom

(with Momoko Williams)

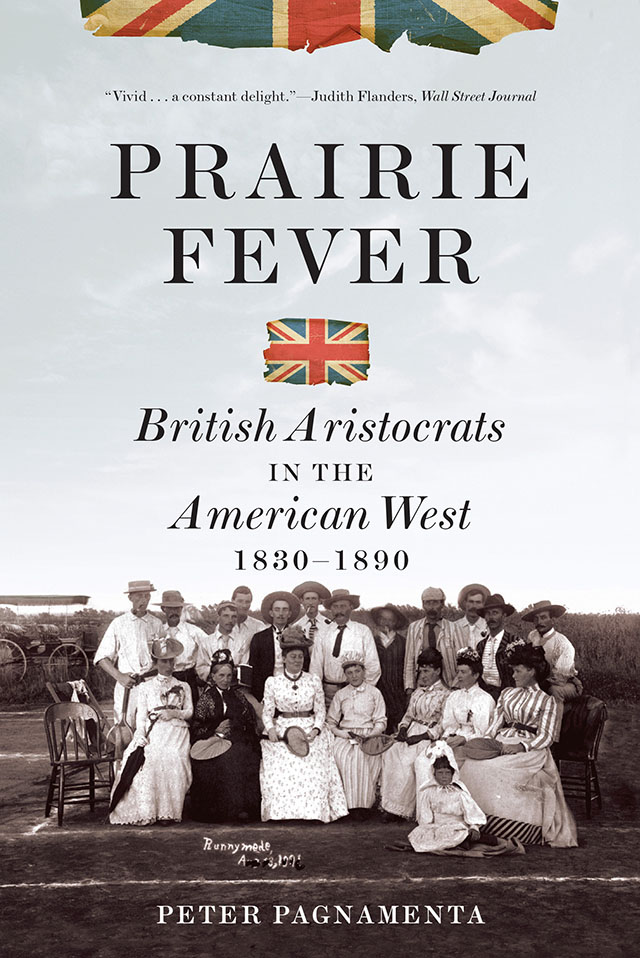

PRAIRIE

FEVER

British Aristocrats in the

American West 18301890

PETER PAGNAMENTA

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

Contents

`The prairie fever! I feel it now! While I am penning these memories, my fingers twitch to grasp the reinsmy knees quiver to press the sides of my noble horse, and wildly wander over the verdant billows of the prairie sea.

CAPTAIN MAYNE REID , The Scalp Hunters , 1851

Introduction

I n the spring of 2010 I met a farmer with 1,600 acres of flat and fertile prairie in south-central Kansas. He told me how, on hot summer nights after the wheat harvest, as he roared across the fields plowing in the stubble, the rack of spotlights mounted on his 280-horsepower tractor picked out a myriad of dazzling sparkles from the newly turned earth. The reflections were thrown back by fragments of broken glass, and he believed these were from the old liquor and beer bottles cast aside by the British boys. The story of Runnymede, a township of British gentlemen that existed for a few years in the 1880s and 90s, failed, and was then demolished, forms a vivid part of Harper County history. Local mythology harks back to a time when well-to-do Englishmen bought land, played tennis on the prairie, put on scarlet coats to chase after coyote, laid out a steeplechase course, and spent much of their time carousing, hence the glass.

It is possible to find more substantial traces of the upper-class British involvement with the American West. Major art galleries in Denver, Omaha, Fort Worth, and other cities show early pictures of the Rockies and the Indians that were commissioned by British travelers. Out on the range, breeds of cattle and horses can be traced back to blooded livestock brought in by Britons with capital. In northwest Iowa, in the small community of Brunsville, another farmer showed off his hay barn, strongly built to the specifications of a British admiral, which has survived 130 years of tornadoes and winter storms, and his substantial British-built house. He pointed to where the line of stables for the polo ponies once stood, and the flat paddock by a creek, where the British boys played practice games. In nearby Le Mars, once the headquarters of the largest British community to be defined by the social background of its members, a small wooden church, with brass fittings and a lectern sent out from England, still stands on First Avenue. Built in prairie Gothic style, with funds solicited from home, St. Georges provided Anglican services for the genteel British settlers of Plymouth County, led by an imported Church of England clergyman. For Le Mars residents today, the British era, with its boisterous behavior, horse racing, and polo, represents the most colorful and cosmopolitan strand of the towns early history.

The handful of British colonies that sprung up in the 1870s and 80s were just one more manifestation of an interest which began just as Queen Victoria came to the throne, and which was to take several different forms over the following fifty years, and whose turns and tensions are followed in this book. Mass emigration across the Atlantic was building up over the same period, but this is not a story of the huddled masses, who crossed the Atlantic in steerage, but of the well-off classes, who traveled in the comfort of the saloon deck, often with return tickets. It tracks a strange and at times controversial encounter, as a class of people who were quite unlike other new arrivals, and had no match in the United States, were drawn to a landscape and a young society that had no equivalent in Europe. Inevitably, frictions arose. Arriving with their own preconceptions and engrained attitudes, the British often clashed with frontier Americans with different priorities and concerns.

The influx of titled grandees and well-born Britons was just a small eddy in the great tide of incoming settlers and emigrants that washed across the country in the nineteenth century. They were never more than a few thousand, but their financial resources, energy, and self-confident behavior gave them significance far beyond their number. They began to arrive in the 1830s, bringing their dogs, and sometimes their valets and servants, and making their way across the prairies. At first they came only in search of adventure, taking lengthy trips to see the Indians and hunt bear and buffalo, wapiti, and mountain sheep. As the frontier advanced, their reasons for coming out changed too, and not all were members of the nobility. The wealthy aristocrats, who had mounted extravagant hunting expeditions in the early years, were joined by what in Britain was called the gentry, members of country families who had large holdings of land and inherited wealth, and enjoyed a social position, though they did not hold titles.

The frenzy of buffalo killing was followed by attempts to solve the pressing social problem that worried many upper-class families at homewhat to do with their younger sons. For a while the West seemed to offer an answer, when it was thought a country gentlemans lifestyle could be established in Kansas or Colorado. Then, in the final round of this engagement, during the prairie cattle boom, the aristocrats joined in the beef business, stepping down from the Pullman cars of the transcontinental trains in Wyoming, Nebraska, or Texas to buy herds of animals, and then millions of acres of land. But their hopes that they could restore or increase their wealth at a time of agricultural depression in England, and a worsening political situation in Ireland, were to be disappointed. The bonanza collapsed as fast as it had risen, through a combination of overgrazing and unusually savage winters.

In one sense the story of this preoccupation with the prairies is a part of British social history. As well as demonstrating the lengths to which the aristocracy would go to exercise their innate proclivity for hunting, it reflects their private insecurities, on their own home territory, as the nineteenth century advanced. They worried about the rise of a middle class who seemed to be usurping their old political power, about farm prices and the threat of land reform to relieve their tenants. They were concerned about the prospects for younger members of their families, who would not acquire landed estates because of the tradition of primogeniture inheritance, and who found openings in the army or the civil service more difficult to secure because of new government reforms. But the real narrative comes from what happened on the ground, in the territories and new states, when the aristocratic incomers met the crude democracy of the American frontier.

As the first travelers made their way from the East Coast to the setting-off points for Indian territory along the Missouri, they had their first experience of the brash new United States, which figured so largely in the British mind with a mixture of fascination and fear. Along with so many visitors, including Mrs. Trollope, the list of their complaints was often trivial. They decried the ill-kempt nature of the New York streets and the poorly laid pavements, the rudeness of railway staff, the excessive handshaking to be endured when being introduced or greeted, the torrential amount of spitting, and the overfamiliarity of fellow passengers on the steamboats.

Next page