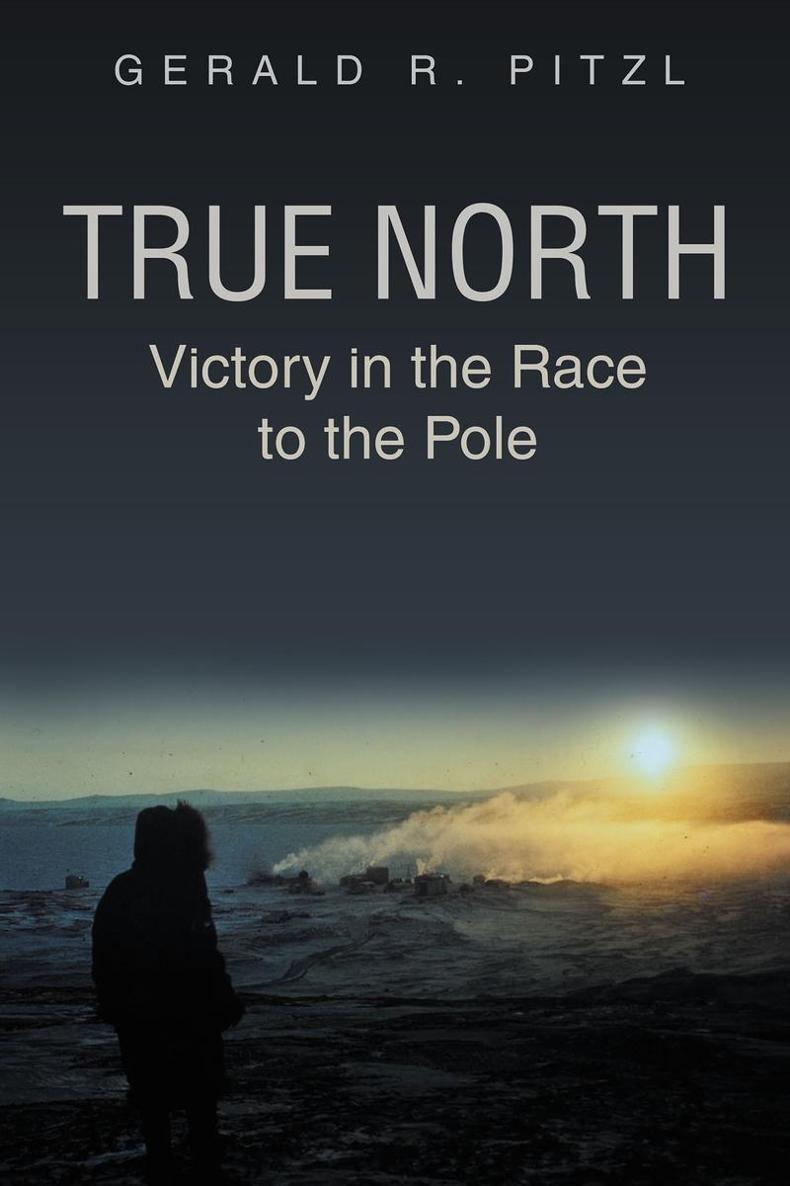

True North

Victory in the Race to the Pole

Gerald R. Pitzl

Copyright 2021 Gerald R. Pitzl, Ph.D.

All rights reserved

First Edition

PAGE PUBLISHING, INC.

Conneaut Lake, PA

First originally published by Page Publishing 202 1

ISBN 978-1-6624-1674-3 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-6624-4525-5 (hc)

ISBN 978-1-6624-1675-0 (digital)

Printed in the United States of America

Table of Contents

For Ralph Plaisted, Dr. Arthur Aufderheide, Donald Powellek, Jean Luc Bombardier, Walter Pederson, George Cavouras, Lt.Col. Andrew Horton, Welland Phipps, Kenneth Lee, Richard Dublicky, other expedition members from 1967, families, friends, and long-time supporters

The first verified surface expedition to reach the North Pole was led by American explorer Ralph Plaisted [using] snowmobilesin 1968. (https://nationalgeographic.org/plaisted/)

The first undisputed overland trek to the North Pole wasnt made until 1968, when a party led by Ralph Plaisted arrived by snowmobile. (https://www.smithsonian.com/plaisted/)

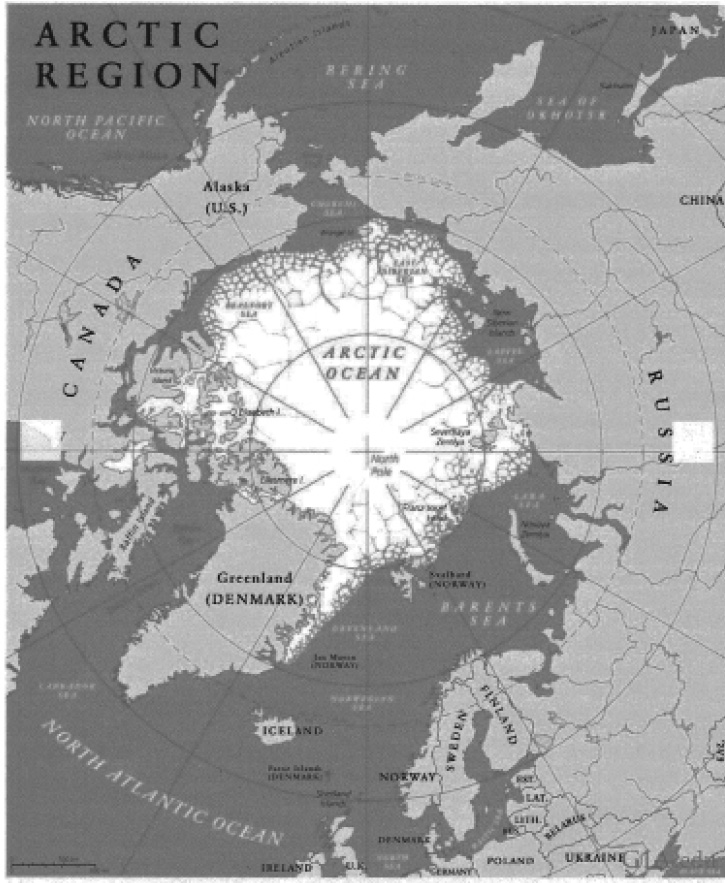

The earliest indisputable attainment of the North Pole by surface travel over the sea ice took place at 3 PM (Central Daylight Time) on 19 April 1968, when Ralph Plaisted (USA), accompanied by Walter Pederson, Gerald Pitzl and Jean Luc Bombardier, reached the North Pole after a 42-day trek on snowmobiles. (https://guinessbookofrecords.org/plaisted/)

R. L. Plaisted led a successful expedition from a base camp on Ward Hunt Island to the North Pole in March-April [1968], the journey beginning on 7 March and ending forty-three days later, on 19 April. (https://cambridge.org/polarrecord/plaisted/)

Our last campsite was established on April 18. Over the next thirty-six hours, I determined our position by celestial navigation to be four nautical miles from the North Pole at a latitude of eighty-nine degrees and fifty-six minutes north, and a longitude of ninety-five degrees west. On the morning of April 20, we traveled those remaining miles to the latitude of ninety degrees north. Verification of attainment came with an air force overflight at 10:30 a.m. CDT on April 20. The total number of days on the ice was forty-four. GRP

Prologue

On May 4, 1967, the ice party of the first Plaisted Polar Expedition emerged from their tent into bright sunlight. The previous seven days and nights had them locked in their tents, listening to an unrelenting windstorm, an Arctic blow, as the triple-walled Arctic tent that was home shook endlessly. A check of latitude had them at 83 degrees and 36 minutes north after more than five weeks of travel and still 324 nautical miles from the North Pole. The season for such surface ventures was fast closing, and temperatures would be rising quickly over the next few weeks. There would still be a navigable ice surface, but it was not likely that the open water encountered upon going north would freeze and allow safe crossing. They were at the end of an adventure that had proven to be both incredibly fascinating and severely frustrating. It also ended in embarrassment, especially because we had a film and sound team from CBS with us to record our efforts, headed by Charles Kuralt, the famed reporter. We had been desperate to succeed.

The team had worked for a year preparing for this North Pole adventure. We religiously followed a US air force fitness program, practiced snowmobile driving on the frozen lakes of Minnesota (for me, this was my first time on such a conveyance), studied the environmental aspects of the remote region we would enter, wrote hundreds of letters requesting everything from navigation chronometers from Hamilton Watch Company to candy bars from the Pearson Company in St. Paul, and wondered all through the training what it would be like to travel in the deep Arctic on snowmobiles in negative-fifty-degree weather. A librarian at the University of Minnesota High School in Minneapolis where I taught eleventh-grade Area Studies surprised me with a small bottle of blue-colored liqueur with a tag attached reading North Pole Snake Bite Preventative: To Be Taken Internally Daily to Ward Off Poisonous Polar Snakes. I still have the tag.

With primary responsibility for gathering environmental information, I had traveled to Ohio State University to visit their world-famous Polar Institute. The timing of my visit was opportune because the faculty and graduate students were gathering for their weekly Friday-afternoon coffee hour.

Colin Bull, the director of the institute introduced me with these words: This is one of the expedition members planning to carry snowmobiles to the North Pole.

Carry snowmobiles? That was shocking. In my mind was the unfounded belief that our team, once on the ice, could reach the North Pole easily within two weeks. Was I ever wrong! One could study aerial photos of the pack ice, select routes around the buildups of ice as pictured; but until confronted head-on, you did not realize what a formidable barrier to unhindered travel the ice could be.

It was clear what had stopped us in 1967. The jumping-off point for the traverse was a weather station called Eureka, six hundred nautical miles from the pole. Other expeditions had started from locations much farther north, as would this group on the next attempt in 1968. Our departure date was way too late. The end of February or early March was the ideal time to launch; this team did not get on the ice until late March. The snowmobiles were sturdy but underpowered for the demands of the virtually indescribable ice surface of the Arctic Ocean and for pulling sleds that were far too overloaded with what turned out to be unneeded equipment.

Walt Pederson, our snowmobile mechanic and ice party member later remarked, These snowmobiles were too weak to even hurt themselves!

There were full days of operation that resulted in accumulating a mere two or three miles northward. Finally, there were numerous logistics delays due to adverse weather conditions and necessary airplane maintenance. The ice party was resupplied every week or ten days by aircraft operating from the base camp at Eureka.

Despite the disappointment of having to withdraw from battle, the team was already planning for another Arctic campaign in 1968. In order to succeed, we realized we would have to start a month earlier, find a base camp somewhere on the north coast of Ellesmere Island closer to the pole, acquire more powerful snowmobiles, travel lighter, and put into practice the lessons learned on this expedition.

Art Aufderheide, our resident doctor, a pathologist, by the way, concluded his journal this way: What will it be like next year?

Well, as it turned out, that nasty ice surface would again bring challenges, open water areas would delay us until we found ways to go around them or wait for the surface to freeze and then drive across, more Arctic blows would stop us, and we would try patiently to endure a plethora of logistical delays. But the reward at the end of the forty-four-day journey would be reaching the North Pole and having the attainment verified.

What follows is the navigators story of this once-in-a-lifetime experience, a critique of Commander Pearys navigational decisions on his 1909 expedition, and an attempt at clarifying some of the unfortunate results of polar politics once the expedition was completed.