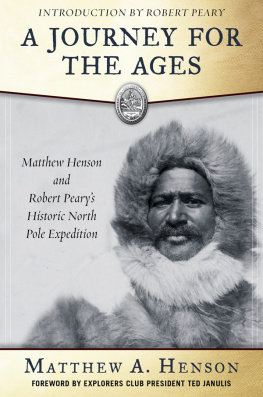

First published 1912 as A Negro Explorer at the North Pole by Frederick Stokes Skyhorse Publishing edition 2016

All rights to any and all materials in copyright owned by the publisher are strictly reserved by the publisher.

Introduction 2016 Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Tom Lau

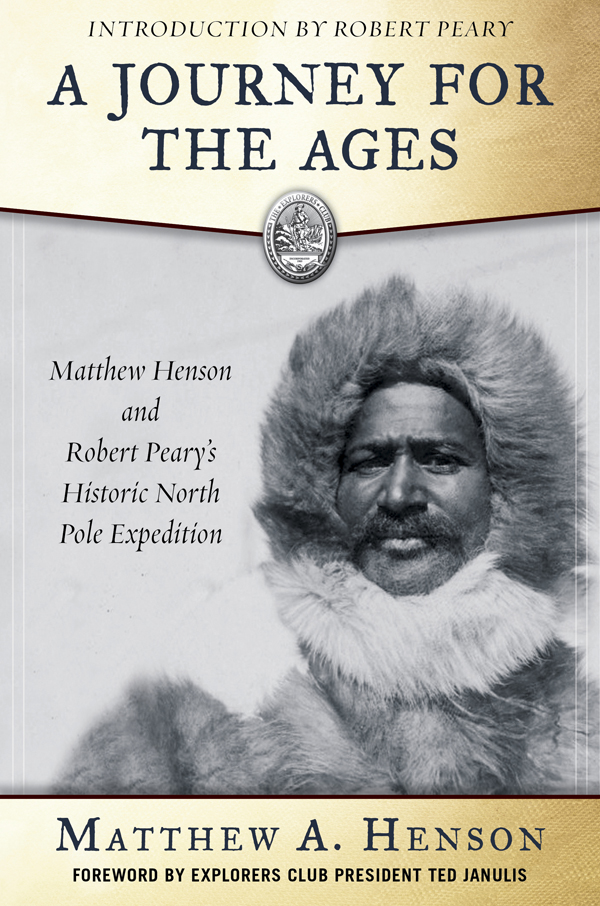

Cover photo used with permission by the U.S. Library of Congress

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-0755-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-0757-3

Printed in the United States of America

T ABLE OF C ONTENTS

T HE E XPLORERS C LUB

History and Mission Statement

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS FOR THE 2016 EDITION

A Journey for the Ages: Matthew Henson and Robert Pearys Historic North Pole Expedition by Matthew A. Henson is once again in print with a new title. The Explorers Club, in collaboration with Jay Cassell, Editorial Director at Skyhorse Publishing, is pleased to be reprinting our 2009 edition of this outstanding book, Volume V in our Classic Series collection.

Even a reprint of our own edition had behind the scenes efforts by many. A special thanks goes to Explorers Club President, Ted Janulis, for his enthusiasm and support. Additional thanks go to Henson scholar, S. Allen Counter, for writing a new introduction; Executive Director, Will Roseman; Curator of Collections, Lacey Flint; George Gowen; and Veronica Alvarado. This printing also includes the introduction written by Deidre Stam for our 2009 edition.

Jay Cassell at Skyhorse Publishing stepped forward to keep our Classic Series books in print. These books represent our continuing commitment to excellence in exploration.

--Lindley Kirksey Young

The Explorers Club

March 2016

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2016 EDITION

One hundred years after he returned from the northernmost point on our planet, to little applause and less recognition, the Arctic explorer extraordinaire Matthew Henson was given a long-desired official title and rank by the United States Navy. In 1909, Henson, an African-American, trekked some 500 miles on the Arctic ice by dogsled with Commander Robert E. Peary and four Inuit associates (then called Polar Eskimos)named Ootah, Egingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueahto 90 degrees North latitudethe North Pole. They were most likely the first human beings to stand at the top of the Earth.

Some of Pearys detractors, particularly those who supported his adversary, Frederick Cook (who falsely claimed to have reached the Pole in 1908), have conjectured that Peary and Henson never quite reached their goal. My colleagues at Harvard and I, however, as well as a group of U.S. Navy admirals in the Navigation Society and others who have analyzed their records and scientific data, are convinced that Peary, Henson, and their Inuit assistants did in fact attain the North Pole as they said.

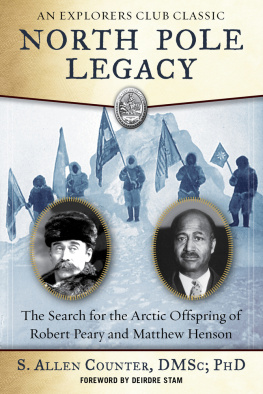

For years, I waged a struggle to gain proper recognition for Hensons remarkable achievements. As an explorer and a member of the Explorers Club of New York, I had always considered Henson a great role model and the unsung hero of Arctic exploration. In researching for my book North Pole Legacy , I had the opportunity to interview older members of the Explorers Club, such as Terris Moore and Brad Washburn, who had known Henson personally. They, without reservation, called him one of the greatest Arctic explorers the world has ever known. In 1937, the renowned Danish explorer Peter Freuchen nominated Henson for membership in the then all-white club (Peary had been a member since 1904), arguing that he had been excluded only because of the racial bias of its members. Freuchen told the clubs officers, In Scandinavia, we do not treat the question of Negro equality as deplorably as you do in America.

Henson died in New York in 1955, at eighty-eight years old. His funeral at New Yorks Abyssinian Baptist Church was attended by more than 1,000 friends and admirers. Over the years, a number of distinguished Americans had attempted to procure what Hensons wife Lucy had once called proper and deserved recognition for this proud black man who was born in Charles County, Maryland, three years after the abolition of slavery, but he died relatively obscure outside the black community.

In 1931, U.S. Navy Admiral Donald B. MacMillan, a native of Massachusetts who had been a member of the 1909 North Pole expedition, asked Congress to create an award for Henson. In a letter to Congress, MacMillan wrote

In consideration of the very valuable work of Matthew A. Henson, assistant to Peary for eighteen years (1891-1909), I would suggest a special medal to be awarded by Congress. Henson went to the Pole with Peary because he was a better man than any man in Pearys party. In fact, he was of more value to Commander Peary on the Polar Sea than all white men combined. Race, creed, or color should not stand in the way of recognition.

Henson did not receive recognition from Congress at that time. In fact, one Congressman indicated his unwillingness to introduce the name of a Negro on the House floor.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, leaders in the African-American community, and some whites such as MacMillan and Admiral Eugene McDonald of the Chicago Geographic Society, continued to seek recognition for Hensons contributions to Arctic exploration. On April 6, 1954, nearly half a century after he planted an American flag in the icepack at the Pole and the year before his death, Matthew and Lucy Ross Henson were honored with an invitation to the White House, where they were welcomed by President Dwight David Eisenhower.

Decades later, I petitioned the U.S. Navy to grant Henson special recognition for his dedicated service, and recommended that a ship be named in his honor. Finally, with the support of both military and civilian leaders, this recommendation was honored. In 1996, the U.S. Navy invited me to escort Hensons great-niece, Audrey Mebane, a retired school teacher in Washington, D.C., to Moss Point, Mississippi, to participate in launching the TAGS 63 explorer ship U.S.N.S. Henson . A year later, I traveled on the Hensons maiden voyage, along with my then-twelve-year-old daughter Philippa.

I spent more than twelve years petitioning the National Geographic Society, particularly the Gilbert Grosvenor family, who own the company, to recognize Hensons achievements. In 1906, at the direction of the Grosvenors, National Geographic had given his commander, Robert Peary, its most prestigious award, the Hubbard Gold Medal, to honor his accomplishments in Arctic exploration. At that time, explorers were recognized for record distances traveled toward the North Pole. When National Geographic told Peary that it also wished to give the Hubbard medal to the person on his expedition who came closest after Peary himself in degrees North latitude to the North Pole, he named Matthew Henson, his colored assistant. According to explorer Terris Moore, the heads of National Geographic responded, No, we mean the other white man who came closest. The Hubbard Gold Medal was presented to Robert Bartlett, who by his own admission never traveled farther than 87 degrees North latitude, about 125 miles from the Pole, before he was sent back to base camp so that Peary would be the only white man recognized as the first to stand at the top of the planet (and some believe, because Bartlett was Canadian). It wasnt until 2000, after my string of letters to members of the board of National Geographic , that the organization finally granted Henson his long-overdue Hubbard gold medal.