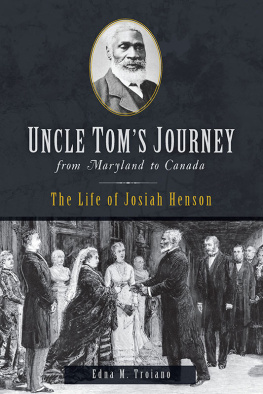

Josiah Henson and Uncle Tom

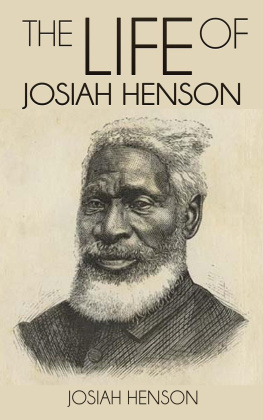

Of the many narratives written for, and on occasion by, fugitive slaves who fled from the United States to the provinces of British North America before the Civil War, no single book has been so widely read, so frequently revised, and so influential as the autobiography of Josiah Henson. For Henson came to be identified with one of the best known figures in Nineteenth Century American literature, the venerable and self-sacrificing Uncle Tom of Harriet Beecher Stowes most famous novel. To the popular mind then, and to many people now, Henson was undeniably Tom, the very figure from whom Mrs. Stowe borrowed large elements of plot and characterization, the figure who came to symbolize the successful fugitive, the man who permanently settled in Canada and there won fame, if not fortune, and a permanent place in the history of the abolitionist struggle.

Indeed, Hensons fame is assured, for even he came in time to believe that he was the original Uncle Tom, and his neighbors accepted this evaluation. His cabin and grave, in rural Ontario, became tourist attractions, and Dresden, ironically the center of the provinces most clearly practiced color bar in the 1950s, advertised itself as the Home of Uncle Tom. At first untended, but from 1930 looked after by the Independent Order of the Daughters of the Empire and later by the Dresden Horticultural Society, the grave became the scene of Negro Masonic pilgrimages. Hensons house was opened as a museum in 1948, and the cemetery of the colony of which the house was a part was restored by the National Historic Sites Board of Canada, with plans afoot to recreate a portion of the community itself, both to instill civic pride in Negro Canadians and as a tourist attraction. The Historic Sites Board gave the considerable force of its approval to the Henson saga when it placed a plaque near the restored home in honor of the man whose early life provided much of the material for... Uncle Toms Cabin.

Henson became one of the best known of all fugitive slaves, the several editions of his narrative one of the most frequently consulted sources, his life thought to be the archetypical fugitive experience. The first version of his autobiography, published in 1849, is without guile, straight-forward, dramatic in its simplicity. But this fugitive from Kentucky, clearly intelligent and hard-working, also shared the normal desire to collect a few of the merit badges that life might offer, and when he found himself thrust into fame in a role that just might fit, he hugged his new role to himself until his death. To his credit, not until he was old and senile did Henson ever claim to be Uncle Tom, but he did nothing to stop others from making the claim for him. Those versions of his autobiography which appeared after the publication of Uncle Toms Cabin in 1852 showed substantial alterations, extensions, and fabrications, and the fullest of these accounts, ghost-written for Henson by an English clergyman-editor, John Lobb, while now extremely scarce, deserves to be brought back into print not only for what it tells us about Henson and the fugitive slaves, but for the fullness of detail it provides, most of it accurate, about fugitive life in Canada, and for the almost classic opportunity it affords to study the ways in which texts might be altered to serve a cause.

For the cause of the abolitionists was served well by Hensons narrative. In many ways his saga is illustrative of the problem of the intelligent fugitive slave of the time: Henson was seldom left free to be himself, to assimilate if he wished into the mainstream of Canadian lifeeven of black Canadian lifefor he became the focus of abolitionist attention, a tool to be used in a propaganda campaign which was not above much juggling with the facts, however proper its ultimate goals may have been. For these reasons his life, and his autobiographical account of it, deserve examination in some detail. And that life, and narrative, must be seen against the background of the efforts made by and on behalf of the fugitive slaves to found all-Negro colonies in Canada West, or present-day Ontario. The most significant of these attempts was one initiated in 1842 under the promising name of Dawn, and it is with Dawn that we associate Hensons Canadian sojourn.

Dawn represented one attempt to adjust to the presumed realities of a white America. No less than the European immigrants of the time, some Negroes believed in the success ethic that lay behind one of the United Statess chief messages to the world: hard work, clean living, education, and an eye for the main chance would bring a man, at least a free man, even if blackand unless flawed by character or caught by bad luckto the top. However, the Negro was flawed, in the eyes of many, by character and certainly by luck, in terms of the hard truths of a white world, and enough realized that the demise of slavery alone (which surely was coming) was not enough to give the Negro his place in the line inexorably marching toward success. Manual labor institutes, practical training, the fundamentals of a bookish education, and some understanding of how a capitalist economy actually worked were essentialor so Josiah Henson would argue later in his autobiography. A brief escape from the world was needed so that the Negro might master these tools, so that he might catch up with the white man, who had not been deprived of the necessary knowledge. A firm belief in education and the instant status it gave lay behind the many assumed titles, the Doctors, Professors, and Right Reverends who sprang so quickly from their soil. In a communal society, the Negro could train himself to use freedom, could come to follow the mores, to reflect the virtues, to accept the ethics of the dominant white society. In short, the values of the Negro community experiments were normative ones. The Negroes accepted the social environment of the North much as it was, or as they saw it to be, and they did not intend to retreat from it permanently or to reform it. Rather than turning their backs upon white society, they sought a temporary refuge in which to prepare for a full place in that society.