PREFACE.

Table of Contents

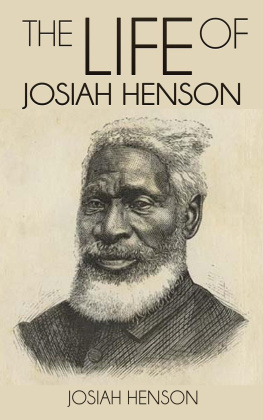

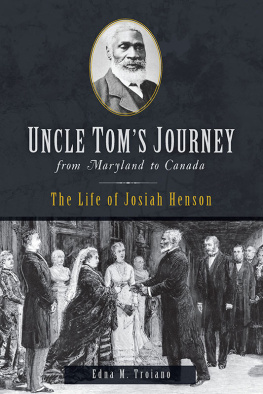

The numerous friends of the author of this little work will need no greater recommendation than his name to make it welcome. Among all the singular and interesting records to which the institution of American slavery has given rise, we know of none more striking, more characteristic and instructive, than that of Josiah Henson .

Born a slavea slave in effect in a heathen landand under a heathen master, he grew up without Christian light or knowledge, and like the Gentiles spoken of by St. Paul, "without the law did by nature the things that are written in the law." One sermon, one offer of salvation by Christ, was sufficient for him, as for the Ethiopian eunuch, to make him at once a believer from the heart and a preacher of Jesus.

To the great Christian doctrine of forgiveness of enemies and the returning of good for evil, he was by God's grace made a faithful witness, under circumstances that try men's souls and make us all who read it say, "lead us not into such temptation." We earnestly commend this portion of his narrative to those who, under much smaller temptations, think themselves entitled to render evil for evil.

The African race appear as yet to have been companions only of the sufferings of Christ. In the melancholy scene of his deathwhile Europe in the person of the Roman delivered him unto death, and Asia in the person of the Jew clamored for his executionAfrica was represented in the person of Simon the Cyrenean, who came patiently bearing after him the load of the cross; and ever since then poor Africa has been toiling on, bearing the weary cross of contempt and oppression after Jesus. But they who suffer with him shall also reign; and when the unwritten annals of slavery shall appear in the judgment, many Simons who have gone meekly bearing their cross after Jesus to unknown graves, shall rise to thrones and crowns! Verily a day shall come when he shall appear for these his hidden ones, and then "many that are last shall be first, and the first shall be last."

Our excellent friend has prepared this edition of his works for the purpose of redeeming from slavery a beloved brother, who has groaned for many years under the yoke of a hard master. Whoever would help Jesus, were he sick or in prison, may help him now in the person of these his little ones, his afflicted and suffering children. The work is commended to the kind offices of all who love our Lord Jesus Christ in sincerity.

H. B. STOWE.

Andover, Mass. , April 5, 1858.

FATHER HENSON'S STORY

OF

HIS OWN LIFE.

CHAPTER I.

MY BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD.

Table of Contents

EARLIEST MEMORIES.BORN IN MARYLAND.MY FATHER'S FIRST APPEARANCE.ATTEMPTED OUTRAGE ON MY MOTHER.MY FATHER'S FIGHT WITH AN OVERSEER.ONE HUNDRED STRIPES AND HIS EAR CUT OFF.THROWS AWAY HIS BANJO AND BECOMES MOROSE.SOLD SOUTH.

The story of my life, which I am about to record, is one full of striking incident. Keener pangs, deeper joys, more singular vicissitudes, few have been led in God's providence to experience. As I look back on it through the vista of more than sixty years, and scene on scene it rises before me, an ever fresh wonder fills my mind. I delight to recall it. I dwell on it as did the Jews on the marvellous history of their rescue from the bondage of Egypt. Time has touched with its mellowing fingers its sterner features. The sufferings of the past are now like a dream, and the enduring lessons left behind make me to praise God that my soul has been tempered by him in so fiery a furnace and under such heavy blows.

I was born June 15th, 1789, in Charles county, Maryland, on a farm belonging to Mr. Francis Newman, about a mile from Port Tobacco. My mother was a slave of Dr. Josiah McPherson, but hired to the Mr. Newman to whom my father belonged. The only incident I can remember which occurred while my mother continued on Mr. Newman's farm, was the appearance one day of my father with his head bloody and his back lacerated. He was beside himself with mingled rage and suffering. The explanation I picked up from the conversation of others only partially explained the matter to my mind; but as I grew older I understood it all. It seemed the overseer had sent my mother away from the other field hands to a retired place, and after trying persuasion in vain, had resorted to force to accomplish a brutal purpose. Her screams aroused my father at his distant work, and running up, he found his wife struggling with the man. Furious at the sight, he sprung upon him like a tiger. In a moment the overseer was down, and, mastered by rage, my father would have killed him but for the entreaties of my mother, and the overseer's own promise that nothing should ever be said of the matter. The promise was keptlike most promises of the cowardly and debasedas long as the danger lasted.

The laws of slave states provide means and opportunities for revenge so ample, that miscreants like him never fail to improve them. "A nigger has struck a white man;" that is enough to set a whole county on fire; no question is asked about the provocation. The authorities were soon in pursuit of my father. The fact of the sacrilegious act of lifting a hand against the sacred temple of a white man's bodya profanity as blasphemous in the eye of a slave-state tribunal as was among the Jews the entrance of a Gentile dog into the Holy of Holiesthis was all it was necessary to establish. And the penalty followed: one hundred lashes on the bare back, and to have the right ear nailed to the whipping-post, and then severed from the body. For a time my father kept out of the way, hiding in the woods, and at night venturing into some cabin in search of food. But at length the strict watch set baffled all his efforts. His supplies cut off, he was fairly starved out, and compelled by hunger to come back and give himself up.

The day for the execution of the penalty was appointed. The negroes from the neighboring plantations were summoned, for their moral improvement, to witness the scene. A powerful blacksmith named Hewes laid on the stripes. Fifty were given, during which the cries of my father might be heard a mile, and then a pause ensued. True, he had struck a white man, but as valuable property he must not be damaged. Judicious men felt his pulse. Oh! he could stand the whole. Again and again the thong fell on his lacerated back. His cries grew fainter and fainter, till a feeble groan was the only response to the final blows. His head was then thrust against the post, and his right ear fastened to it with a tack; a swift pass of a knife, and the bleeding member was left sticking to the place. Then came a hurra from the degraded crowd, and the exclamation, "That's what he's got for striking a white man." A few said, "it's a damned shame;" but the majority regarded it as but a proper tribute to their offended majesty.

It may be difficult for you, reader, to comprehend such brutality, and in the name of humanity you may protest against the truth of these statements. To you, such cruelty inflicted on a man seems fiendish. Ay, on a man; there hinges the whole. In the estimation of the illiterate, besotted poor whites who constituted the witnesses of such scenes in Charles County, Maryland, the man who did not feel rage enough at hearing of "a nigger" striking a white to be ready to burn him alive, was only fit to be lynched out of the neighborhood. A blow at one white man is a blow at all; is the muttering and upheaving of volcanic fires, which underlie and threaten to burst forth and utterly consume the whole social fabric. Terror is the fiercest nurse of cruelty. And when, in this our day, you find tender English women and Christian English divines fiercely urging that India should be made one pool of Sepoy blood, pause a moment before you lightly refuse to believe in the existence of such ferocious passions in the breasts of tyrannical and cowardly slave-drivers.