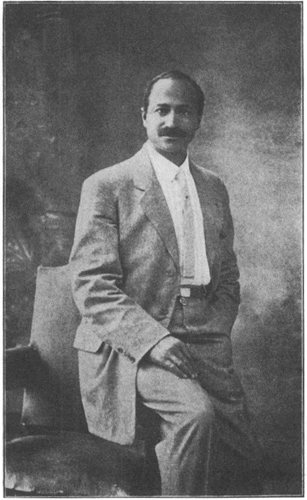

HENSON

at the

NORTH POLE

MATTHEW A. HENSON

Foreword by Robert E. Peary

Rear Admiral, U. S. N.

Introduction by Booker T. Washington

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Bibliographical Note

Henson at the North Pole, first published in 2008, is an unabridged republication of the work first published as A Negro Explorer at the North Pole by Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York, in 1912.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Henson, Matthew Alexander, 18661955.

[Negro explorer at the North Pole]

Henson at the North Pole / Matthew A. Henson ; foreword by Robert E. Peary ; introduction by Booker T. Washington.

p. cm.

Reprint. Originally published: Negro explorer at the North Pole. New York : F. Stokes, 1912.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-78949-1

1. Henson, Matthew Alexander, 1866-1955TravelArctic regions. 2. African American explorersBiography. 3. ExplorersUnited StatesBiography. 4. Arctic regionsDiscovery and exploration. 5. North PoleDiscover) and exploration. I. Title.

G635.H4A3 2008

910.92dc22

[B]

2007050540

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y. 11501

Foreword

F riends of Arctic exploration and discovery, with whom I have come in contact, and many whom I know only by letter, have been greatly interested in the fact of a colored man being an effective member of a serious Arctic expedition, and going north, not once, but numerous times during a period of over twenty years, in a way that showed that he not only could and did endure all the stress of Arctic conditions and work, but that he evidently found pleasure in the work.

The example and experience of Matthew Henson, who has been a member of each and of all my Arctic expeditions, since 91 (my trip in 1886 was taken before I knew Henson) is only another one of the multiplying illustrations of the fact that race, or color, or bringing-up, or environment, count nothing against a determined heart, if it is backed and aided by intelligence.

Henson proved his fitness by long and thorough apprenticeship, and his participation in the final victory which planted the Stars and Stripes at the North Pole, and won for this country the international prize of nearly four centuries, is a distinct credit and feather in the cap of his race.

As I wired Charles W. Anderson, collector of internal revenue, and chairman of the dinner which was given to Henson in New York, in October, 1909, on the occasion of the presentation to him of a gold watch and chain by his admirers:

I congratulate you and your race upon Matthew Henson. He has driven home to the world your great adaptability and the fiber of which you are made. He has added to the moral stature of every intelligent man among you. His is the hard-earned reward of tried loyalty, persistence, and endurance. He should be an everlasting example to your young men that these qualities will win whatever object they are directed at. He deserves every attention you can show him. I regret that it is impossible for me to be present at your dinner. My compliments to your assembled guests.

It would be superfluous to enlarge on Henson in this introduction. His work in the north has already spoken for itself and for him. His book will speak for itself and him.

Yet two of the interesting points which present themselves in connection with his work may be noted.

Henson, son of the tropics, has proven through years, his ability to stand tropical, temperate, and the fiercest stress of frigid climate and exposure, while on the other hand, it is well known that the inhabitants of the highest north, tough and hardy as they are to the rigors of their own climate, succumb very quickly to the vagaries of even a temperate climate. The question presents itself at once: Is it a difference in physical fiber, or in brain and will power, or is the difference in the climatic conditions themselves?

Again it is an interesting fact that in the final conquest of the prize of the centuries, not alone individuals, but races were represented. On that bitter brilliant day in April, 1909, when the Stars and Stripes floated at the North Pole, Caucasian, Ethiopian, and Mongolian stood side by side at the apex of the earth, in the harmonious companionship resulting from hard work, exposure, danger, and a common object.

R. E. PEARY.

Washington, Dec, 1911.

List of Illustrations

Matthew A. Henson

Introduction

O ne of the first questions which Commander Peary was asked when he returned home from his long, patient, and finally successful struggle to reach the Pole was how it came about that, beside the four Esquimos, Matt Henson, a Negro, was the only man to whom was accorded the honor of accompanying him on the final dash to the goal.

The question was suggested no doubt by the thought that it was but natural that the positions of greatest responsibility and honor on such an expedition would as a matter of course fall to the white men of the party rather than to a Negro. To this question, however, Commander Peary replied, in substance:

Matthew A. Henson, my Negro assistant, has been with me in one capacity or another since my second trip to Nicaragua in 1887. I have taken him on each and all of my expeditions, except the first, and also without exception on each of my farthest sledge trips. This position I have given him primarily because of his adaptability and fitness for the work and secondly on account of his loyalty. He is a better dog driver and can handle a sledge better than any man living, except some of the best Esquimo hunters themselves.

In short, Matthew Henson, next to Commander Peary, held and still holds the place of honor in the history of the expedition that finally located the position of the Pole, because he was the best man for the place. During twenty-three years of faithful service he had made himself indispensable. From the position of a servant he rose to that of companion and assistant in one of the most dangerous and difficult tasks that was ever undertaken by men. In extremity, when both the danger and the difficulty were greatest, the Commander wanted by his side the man upon whose skill and loyalty he could put the most absolute dependence and when that man turned out to be black instead of white, the Commander was not only willing to accept the service but was at the same time generous enough to acknowledge it.

There never seems to have been any doubt in Commander Pearys mind about Hensons part and place in the expedition.

Matt Henson, who was born in Charles County, Maryland, August 8, 1866, began life as a cabin-boy on an ocean steamship, and before he met Commander Peary had already made a voyage to China. He was eighteen years old when he made the acquaintance of Commander Peary which gave him his chance. During the twenty-three years in which he was the companion of the explorer he not only had time and opportunity to perfect himself in his knowledge of the books, but he acquired a good practical knowledge of everything that was a necessary part of the daily life in the ice-bound wilderness of polar exploration. He was at times a blacksmith, a carpenter, and a cook. He was thoroughly acquainted with the life, customs, and language of the Esquimos. He himself built the sledges with which the journey to the Pole was successfully completed. He could not merely drive a dog-team or skin a musk-ox with the skill of a native, but he was something of a navigator as well. In this way Mr. Henson made himself not only the most trusted but the most useful member of the expedition.