Copyright

Copyright David F. Pelly, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purpose of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Project editor: Kathryn Lane

Copy editor: Natalie Meditsky

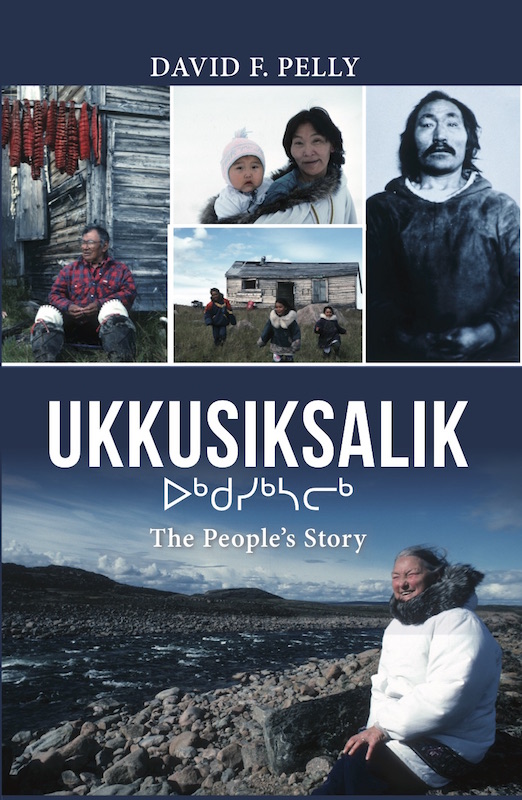

Cover designer: Laura Boyle

Interior design: Courtney Horner

Epub Design: Carmen Giraudy

All photography by the author unless otherwise noted.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Pelly, David F. (David Fraser), 1948-, author

Ukkusiksalik : the peoples story / David F. Pelly.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-4597-2989-6 (bound).--ISBN 978-1-4597-2990-2 (pdf).-

ISBN 978-1-4597-2991-9 (epub)

1. Ukkusiksalik National Park (Nunavut)--History. 2. Inuit-

Nunavut--History. 3. Oral history--Nunavut. 4. Nunavut--History.

I. Title.

FC4314.U45P44 2016 971.958 C2015-906121-0

C2015-906122-9

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and Livres Canada Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

The publisher is not responsible for websites or their content unless they are owned by the publisher.

Visit us at: Dundurn.com | @dundurnpress | Facebook.com/dundurnpress | Pinterest.com/dundurnpress

Dedication

This book is dedicated to the Ukkusiksalingmiut elders, whose generosity

with their knowledge informed this work, even as they enriched my life.

Our shared commitment to pass their stories on to

their grandchildren, and beyond, is now fulfilled.

Foreword

W hen I was a little girl, we lived in Ukkusiksalik as a nomadic Inuit family. My father, Marc Tungilik, and my brother, Kadluk, hunted for all our daily essentials. We were dependent on the animals for both clothing and food, and in the winter seal fat provided the oil for our qulliq ( seal-oil lamp), which gave us light and heat. My mother, Angugatsiaq, prepared the sealskins to make waterproof boots and mitts, and double-sided pack bags for our dogs. We were free to roam the boundless land. Everyone had the freedom to live where they wanted. This is why Ukkusiksalik feels to me like a place of freedom and beauty.

I first met David Pelly in Naujaat (Repulse Bay) when he came to our house in the summer of 1986. I was visiting from Rankin Inlet to see my dad, to help him out and spend time with him. My mother had passed away the year before, and my father would follow her just a few weeks after this visit. It was a pleasure to interpret for David as he asked about Ukkusiksalik, and to hear the stories of my father, who was normally a quiet fellow.

Over the years, David befriended and interviewed many of the people who once lived in Ukkusiksalik. The storytellers were people like Leonie Sammurtok, who became a mother to many children in Chesterfield Inlet; Tuinnaq Kanayuk Bruce, who had memories of life at the Hudsons Bay Company post in Ukkusiksalik; and Mariano Aupilarjuq, the late Inuit historian who was so instrumental in the creation of Nunavut. Several other elders who have left us now told their stories in order to leave behind a record and a sense of how so many of these families were connected.

All the people who were interviewed by David reminisced about their past, remembering how hard it was, but how joyous and free it felt at the time. I, too, was interviewed, which allowed me to look back at my childhood in Ukkusiksalik. I have such fond memories. It was an innocent and joyful time, living in such a beautiful and bountiful place.

I remember one autumn my father was building a rock and sod qarmaq (sod house) for us to live in. I watched him carry very big rocks. I was about three years old. I had just learned to walk again after recovering from polio. But at times I was running after him as fast as I could, sometimes holding my mothers hand. I remember saying to her, My dad is the strongest man on Earth in Inuktitut, of course. I gleamed with pride. I remember when we first occupied the qarmaq , how warm and bright and cozy it felt when my mother lit the qulliq . I was only back there once, forty years later, when I saw that they really were big rocks!

I hope you will enjoy this book. It is a timeless and valuable work of true Inuit history. The land tells its story, as witnessed through the eyes of those we knew who lived in Ukkusiksalik, and those who came before them.

Theresie Tungilik

Ukkusiksalingmiut, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut

Former chair of the Ukkusiksalik Park Management Committee

The language of the Inuit is known as Inuktitut, which literally means sounds like an Inuk.

Preface

H enry Naulaq is a veteran Inuit Broadcasting Corporation cameraman who travelled the North for thirty years. Some years ago, when he saw Ukkusiksalik for the first time, he said, How am I going to do any justice to this kajaanaqtuq in my camera and show it to people who will never see it in person? Kajaanaqtuq means the most beautiful, scenic place in memory, but even as he explains that, he says, he knows the areas significance is rooted more deeply in the people who were there at that wonderful time.

Ukkusiksalik means a place where there is soapstone, or, more literally, the material for a cooking pot. It refers to the whole area surrounding the body of water named Wager Inlet by Captain Christopher Middleton during his 1742 search for the Northwest Passage. Over time, the ancient name came to conjur up much more than just a place where one might find the soapstone needed to make his next pot. It resonates still today as a land of plenty with older people in the Kivalliq region, the mainland part of Nunavut on the west side of Hudson Bay. It calls out to Inuit and qablunaat (white men) alike who have seen it as a beautiful place to visit. Most recently, it has become the name of one of Canadas newest national parks. When the name is used in this book, it refers simply to the area this is the story of that land; it is not the story of a park.

A wise Inuit elder once explained to me that Inuit did not live on the land with any sense of ownership, although their connection to the land could not have been stronger. We have all belonged to this land, he said, turning the Western notion of land ownership on its head. This philosophical perspective underlies the stories captured here. These are stories from the land, as shared with us by some of the elders whose families lived and travelled and hunted in Ukkusiksalik.