Words of the Inuit

CONTEMPORARY STUDIES ON THE NORTH

ISSN 1928-1722

Chris Trott, series editor

8 Words of the Inui t : A Semantic Stroll Through a Northern Culture , by Louis-Jacques Dorais

7 Nitinikiau Innusi: I Keep the Land Alive , by Tshaukuesh Elizabeth Penashue, edited by Elizabeth Yeoman

6 Inuit Stories of Being and Rebirth: Gender, Shamanism, and the Third Se x , by Bernard Saladin dAnglure, translated by Peter Frost

5 Report of an Inquiry into an Injustice: Begade Shutagotine and the Sahtu Treaty , by Peter Kulchyski

4 Sanaaq: An Inuit Novel , by Mitiarjuk Nappaaluk

3 Stories in a New Skin: Approaches to Inuit Literature , by Keavy Martin

2 Settlement, Subsistence, and Change among the Labrador Inuit: The Nunatsiavummiut Experience , edited by David C. Natcher, Lawrence Felt, and Andrea Procter

1 Like the Sound of a Drum: Aboriginal Cultural Politics in Denendeh and Nunavut , by Peter Kulchyski

Words of the Inuit

LOUIS-JACQUES DORAIS

A Semantic Stroll Through a Northern Culture

Words of the Inuit: A Semantic Stroll through a Northern Culture

Louis-Jacques Dorais 2020

Preface Lisa Koperqualuk

24 23 22 21 20 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Contemporary Studies on the North, issn 1928-1722 ; 7

ISBN 978-0-88755-862-7 (paper)

ISBN 978-0-88755-864-1 (pdf)

ISBN 978-0-88755-863-4 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-88755-914-3 (bound)

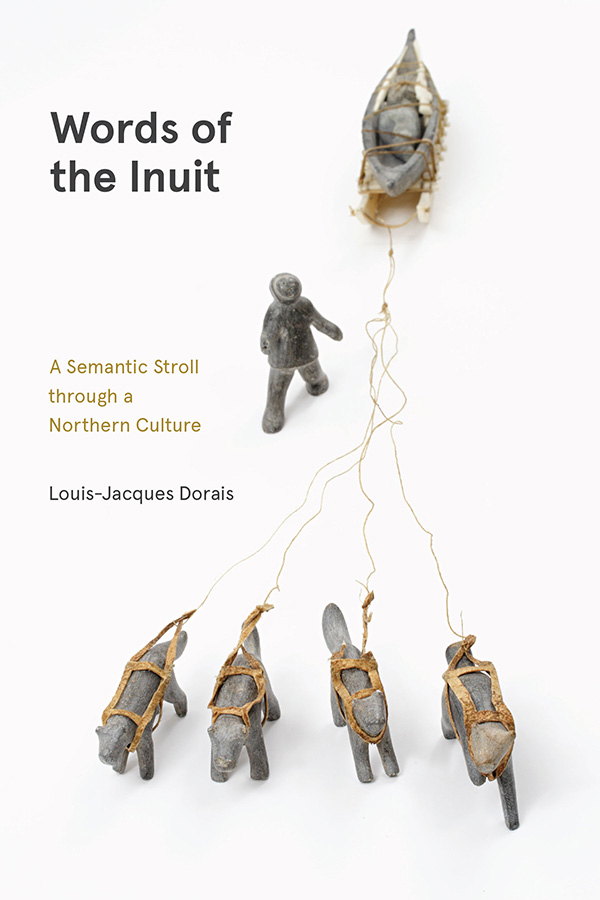

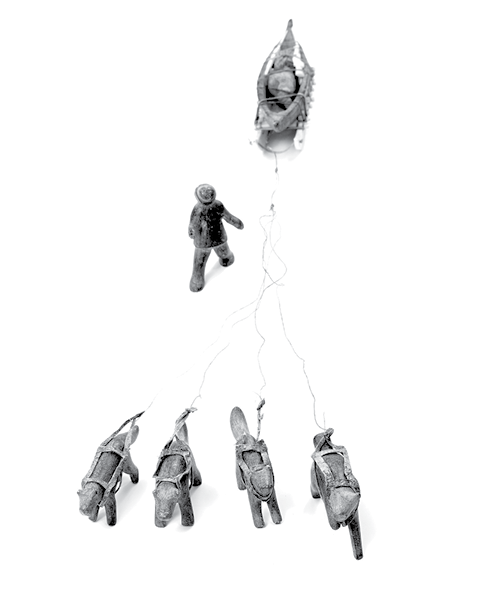

Cover image: Carving, dog sled and hunter. McCord Museum

N-0000.68.1.

Cover design by Marvin Harder

Interior design by Jess Koroscil

Printed in Canada

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Contents

by Lisa Koperqualuk

Preface

By Lisa Koperqualuk

There are so few non-Inuit able to communicate in my language that each time I converse with one who speaks Inuktitut I am usually doubly impressed. With the linguistic structure of our language being so different from English and French, we understand the challenge non-Inuit face when learning Inuktitut. Louis-Jacques Dorais is probably the only ethnolinguist/anthropologist who has such a deep understanding of the Inuit language. He has dedicated most of his life to studying Canadian Inuktitut and teaching it to many students wishing to gain a glimpse of our world and better understand our culture. As I read through Louis-Jacquess book, I see that it brings to light our culture and world view through a stroll among our words and concepts.

When I first met him in the 1980s, Louis-Jacques was assisting the Kativik School Board on a linguistic project related to Inuktitut teaching. Little did I know that one day he would become my director for graduate studies at Laval University in Quebec City. I began my graduate studies with confidence that I would have exemplary guidance, for he knew the Inuit communities in Nunavik and their history, and had delved into our language for a long time.

Even now, I turn to him when I have a question about a specific word. For example, for a chapter in a book about the first bowhead whale hunt in 100 years in Nunavik, published by Avataq Cultural Institute, I needed an explanation for why arvik (bowhead whale) ended with a k , while in Nunavut it was spelled arviq , ending with guttural sound q . I had to find the justification of why, in Nunavik, we said it that way, so that readers of other dialects would not regard it as a mistake. It is interesting and also good to know how our language travelled and to see the path in which its pronunciation evolved, and to have the explanations that help us understand how that happens.

Oftentimes, an Inuk will be told by a parent or someone important in their lives as a way of encouragement, Kajusigit! which basically means Continue or Dont give up! When my grandfather told me this after I had recounted some particular struggle, I took it simply to mean, Keep on going, carry on. Somehow, at that time, his words did not seem like particularly strong encouragement. Our elders in Nunavik and elsewhere use this expression when they really wish to encourage someone not to give up on whatever their endeavour might be. It seems that the deeper meaning, which my grandfather probably understood when he said it to me, really suggests, Be strong, persevere. I think both my examples above answer Louis-Jacquess question of up to what point are etymological studies really significant and socially useful, for understanding the origins of our words is immensely helpful, particularly for those whose work has to do with Inuktitut and/or writing.

This book can be read likewise by an Inuktitut speaker, as well as by a learner or non-Inuktitut speaker, and all will be enriched by it. So much more can be learned about our way of thinking by analyzing Inuktitut in the way Louis-Jacques demonstrates. The study of Inuktitut rests not only in understanding its linguistic structure; a deeper study of our language reveals much more about the Inuit world view. It is this ethonolinguistic approach that brings about very interesting instances where our perception of the world can be better understood.

The chapter dealing with sila and nuna thus reveals the true meaning of these Inuit concepts to the reader. The word sila itself captures different layers of meaning, such as the one of the cosmological regulator of the universe, Silaup Inua , which I enjoyed learning of when I first was introduced to this distinct Inuit concept. And then there are internal and external sila , and their link to a persons mental capacity, wherein a wise and reasonable person is full of sila, is silatujuq . Louis-Jacques allows us to meander thoughtfully through the path he uncovers, layer by layer revealing this and other Inuit concepts such as nuna, earth or land.

Like many other Indigenous languages, we are at a crossroads where many in our communities are seeing our languages slowly deteriorating. We need to make decisions on protecting our language. Work is being done in our institutions to help protect our language, such as with the Inuktitut Language Commission and the Inuktitut language authorities in Inuit Nunangat; but these efforts go hand-in-hand with knowledge of linguistics and semantic understandings of Inuktitut. Words of the Inuit is definitely a resource that must become part of every library in Inuit Nunangat and all schools teaching Inuktitut and Inuit culture and history.

Acknowledgements

For several years, I had entertained the idea of delving more or less systematically into the meanings of Inuit words, in order to decipher the underlying significations many of them hid behind their immediate meaning. Besides anticipating the sheer pleasure of researching a fascinating area of Arctic Indigenous semantics, I wished to bring to light some of the symbolic images underlying Inuktitut, as well as other Inuit languages and dialects.