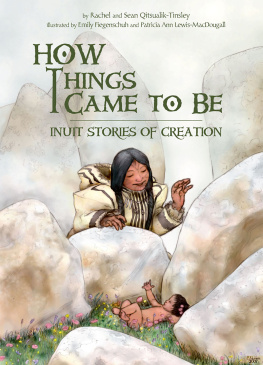

Text copyright 2015 by Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley

Illustrations copyright 2015 by Emily Fiegenschuh and Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall

, illustrations by Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall copyright 2015 by Inhabit Media Inc.

Layout design copyright 2015 by Inhabit Media Inc.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law.

Published in Canada by Inhabit Media Inc.

| Nunavut Office | Ontario Office |

| P.O. Box 11125 | 146A Orchard View Blvd. |

| Iqaluit, Nunavut | Toronto, Ontario |

| X0A 1HO | M4R 1C3 |

| www.inhabitmedia.com |

Credits

Edited by Neil Christopher and Louise Flaherty

Written by Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley

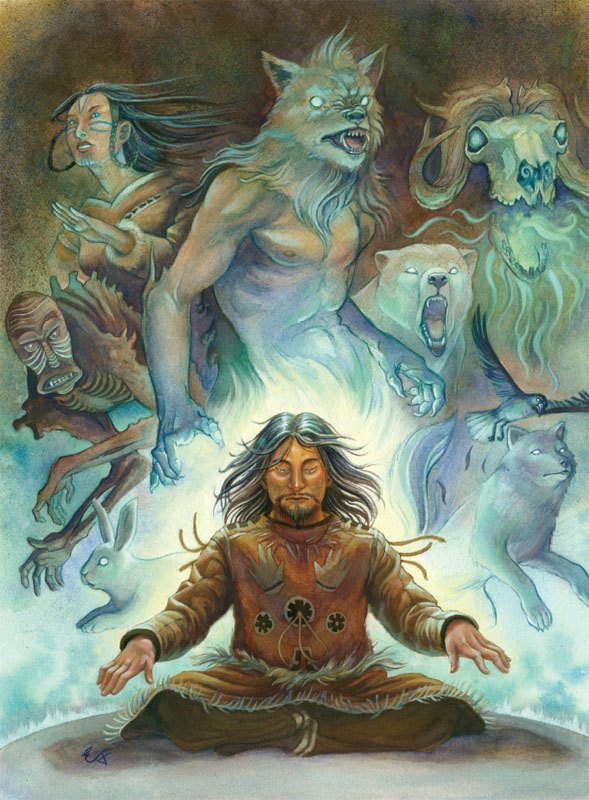

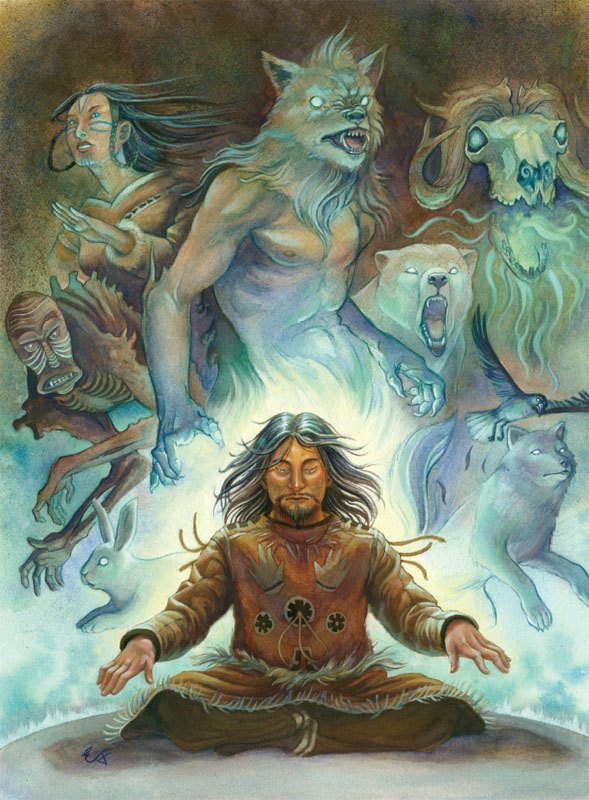

Cover illustration by Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall

When Things Came to Be, The Lands Babies, The Battle of Day and Night, Feathers and Ice, The Deep Mother: Illustrated by Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall

Grand Sky and the Strength of the Land, How Caribou Came to Be, How the Sun and Moon Arose, The Storm Orphans, The One Who is Tied: Illustrated by Emily Fiegenschuh

Cover and interior design by Neil Christopher/Inhabit Media Inc.

978-1-927095-78-2

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Qitsualik-Tinsley, Rachel, 1953

[Qanuq pinngurnirmata]

How things came to be : Inuit stories of creation / written by Rachel and Sean Qitsualik-Tinsley ; illustrated by Emily Fiegenschuh and Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall.

Revision of: Qanuq pinngurnirmata : Inuit stories of how things came to be / written by Rachel A. Qitsualik, Sean A. Tinsley ; illustrated by Emily Fiegenschuh, Patricia Ann Lewis-MacDougall ; [edited by Neil Christopher]. -- Iqaluit, Nunavut : Inhabit Media, 2008.

ISBN 978-1-927095-78-2 (bound)

1. Inuit--Fiction. I. Fiegenschuh, Emily, illustrator II. Lewis-MacDougall, Patricia Ann, illustrator III. Qitsualik-Tinsley, Sean, 1969- author IV. Title. V. Title: Qanuq pinngurnirmata

PS8633.I88Q36 2014 C813.6 C2014-905058-5

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

We acknowledge the support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Book Fund program.

Contents

Introduction:

Grand Sky and the Strength of the Land

Introduction:

Grand Sky and the Strength of the Land

D o we just imagine that things end?

It seems unlikely that one can have a beginning without an end. Inuit imagined an end for this world. But the world is such a tiny place. With its problems and struggles, it is sometimes easy to imagine the world ending. As generations passed, Inuit noticed those problems. Their imaginations began to work.

No matter how sad or scary things got, Inuit held out hope. They hoped, because they believed in more than this little world. They knew there was a Big Everything.

As for this little world, it was just the Land. The Land was delicate. Not always stable. Inuit called it Nuna. This was the surface world, and Inuit imagined different endings for it. Some thought the Land might crack open. That fire would rise up and engulf everything. Others wondered if the Land had a weak spot, something that a powerful being might kick in order to knock the world out of place.

As for the Big Everything, Inuit called that Sila. It was maybe the most important word they knew. It could be used in many ways.

Weather was Sila.

Air was Sila.

Sky was Sila.

Everything was Sila.

Sila was all that one could think of. It was all that lay beyond imagination, too. Sila was the Grand Sky. And thats why, when someone was very, very wise, Inuit said that they were One of Grand Sky.

Inuit never thought of the Grand Sky as having an end. Why would it? Inuit were very practical. Their common sense told them there was no need to say that the Big Everything would disappear. Who might end it? How? And why? They could not imagine any single being calling Stop! to Everything. There were many beings on the Land, in the Sea, and in all the worlds under the Grand Sky. There were furred folk. Feathered folk. Tiny beings. Giants. Invisible creatures and living shadows. None, however, were greater than the Grand Sky.

As Inuit shared the world, they did not feel that they were the reason why Everything existed. Did anything exist for a reason?

Inuit tried to be humble, understanding that they were just one part of something infinite. As for whether life was good or bad: that was up to them. It depended on how they treated each other. They did not bother to imagine a Creator who wanted to someday shut down Creation. Life was not a project.

Some Inuit did imagine something like a Creator. But when they did, this was deeply personal. Like loving a favourite song. Mostly, Inuit tried to respect each other. If someone believed something, that was up to them.

Inuit never worshipped. But they loved deeply. They loved the Land around them. The Sea. The Sky. They hunted in order to stay alive. Life came from life. Life fed on life. Life returned to life. Only this mystery was sacred.

Lives could be big, or small. They could have vast powers, or little at all. But no matter how powerful a being waseven if it was the inventor of day or nightit was still a fellow being. The thinking of those early folk was: why should one being worship another?

Whether walrus or plant root, Inuit knew that everything in nature wished to hold onto its life. Yet there was no life without eating. Human beings could not survive without hunting or picking the occasional plant. But, since all life held power, every life was worthy of respect.

There was no lasting death, since life forcewhether from seaweed or human beingcould not be destroyed. How could one destroy power itself? So, Inuit were most concerned with the treatment of other beings. If one were disrespectful to another life power, one deserved that powers anger.

As Inuit saw it, this was the most sensible way to view the world. Did it not require a power, of some kind, to make the Sun shine? To make lightning flash? They believed that the powers of the first beings were greatest of all. So great that they could become whatever they wished.

A person could become the Sun itself, or the Moon. It was will that drove all. Rage, fear, love: these could move the Land and Sea.

Inuit looked around them. They watched the world. They learned about the Grand Sky. They saw how nature behaved, from the tiniest snowflake to the largest storm. And they believed that they, as children of it all, were simply part of its pattern.

That is why life could shift. It could change, but never truly die.

A beginning suggests an end. But an end suggests a beginning. Since Inuit did not conceive of an end to the Sila, they also never thought of a time when the Sila began. The Sila was like life. Life was like the Sila.

Next page