Contents

Guide

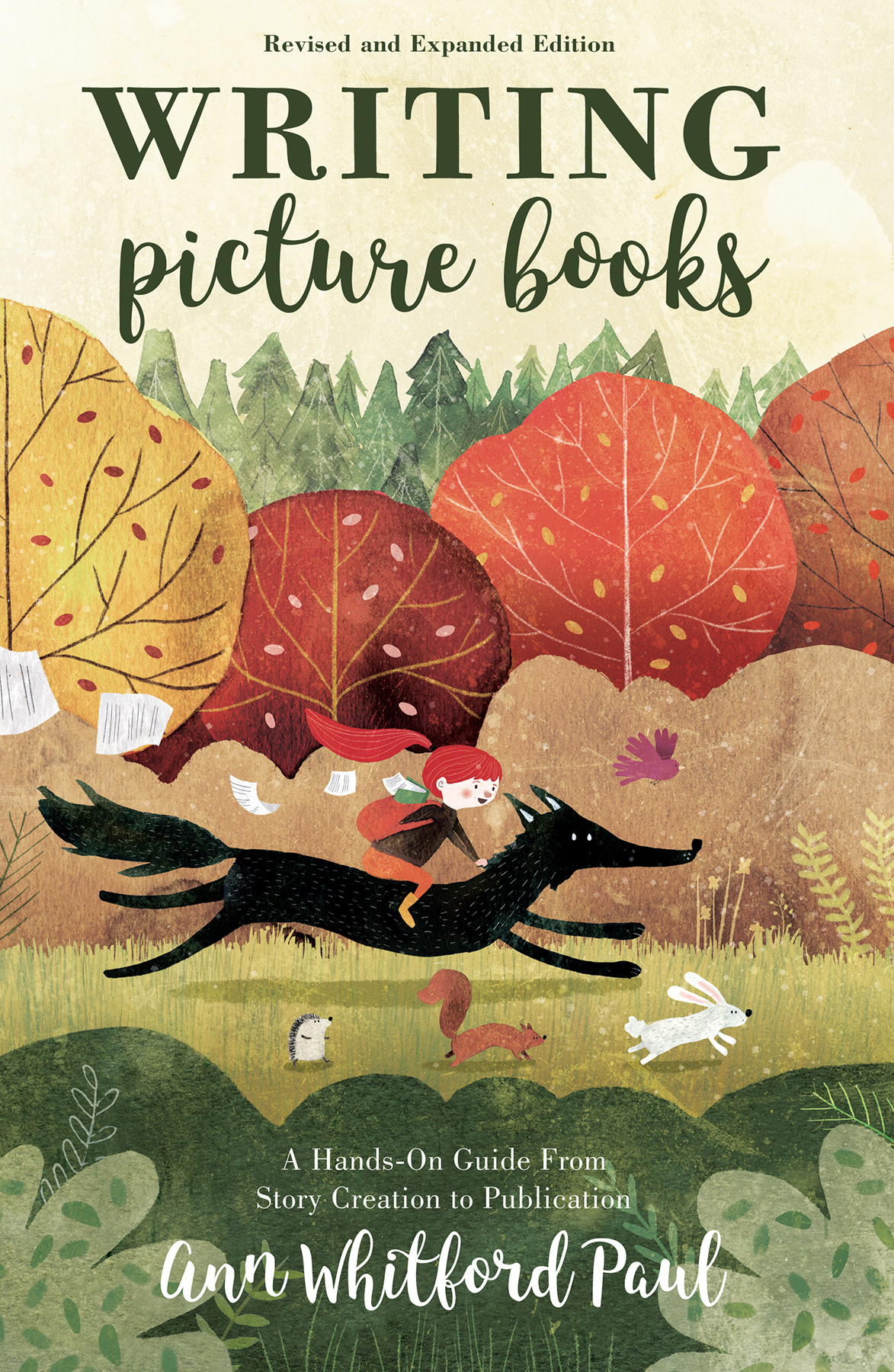

Writing Picture Books

Revised and Expanded Edition

A Hands-on Guide from Story Creation to Publication

Ann Whitford Paul

WritersDigest. com

Cincinnati, Ohio

Dedication

This revised edition is dedicated in loving memory of Sue Alexander, to my special friends and critique partners, Karen B. Winnick and Erica Silverman, who have been with me every step of my writing journey, and to anyone who has ever written or dreamed of writing a picture book.

Proceeds from this book donated by the Ann Whitford PaulWriters Digest Award for the Most Promising Picture Book. Submission instructions can be found at scbwi.org.

Table of Contents

PART ONE

Before You Write Your Story

PART TWO

Early Story Decisions

PART THREE

The Structure of Your Story

PART FOUR

The Language of Your Story

PART FIVE

Tying Together Loose Ends

PART SIX

After Your Story Is Done

Welcome to This Revised and Expanded Book

How can ten years have passed since Writing Picture Books was first published? And nearly twelve years since it was written? Just as much has changed in my life and in yours, in our country, and in our world; so, too, has the field of picture books evolved.

Publishers have continued to merge into bigger organizations, and new smaller publishers have opened their doors to manuscripts. Some publishers still want submissions to arrive via snail mail, but others accept only e-mail attachments. Agents are more necessary than ever to break into the business.

And what about the stories themselves? Since the first edition of Writing Picture Books, editors have been asking for books that are on the cutting edge and break traditional boundaries. One example might be I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen, where it appears the thief character suffers a grisly consequence for his crime.

Narrative nonfiction, where plotting and other techniques of fiction are applied to nonfiction, has become a popular buzz phrase. Picture-book poetry collections now need a theme or story format, not just a smattering of different subjects on which the poet focused. In addition, as attention spans have been reduced by television, video games, smartphones, and computers, publishers have begun asking for shorter manuscripts.

Internet sales have skyrocketed, but independent bookstores have struggled. A high percentage of books, instead of being purchased by professional teachers and librarians, are sold to parents. Then theres the phenomenon of self-publishing, which has allowed rejected writers an alternative way to get their stories into the world.

All these developments and more will be addressed in the following pages. If you have read the first edition, you will still find much fresh material here. The excerpts from published books have been updated, and the examples and quizzes have been rewritten. New chapters have been added, and discussion of the publishing business has been revised to include current information and requirements.

All of this was done with the hope of easing your journey into the land of picture-book publication. May your travels be happy and successful.

Prologue

I love revisions. Where else in life can spilled milk be transformed into ice cream?

KATHERINE PATERSON

Completing a draft of your story isnt the end of the writing process; its the beginning. Then you must shape your draft into a publishable manuscript. This is the fun part of writing, the time-consuming part of writing, and what separates the amateur from the professional. Writing Picture Books Revised and Expanded Edition: A Hands-on Guide from Story Creation to Publication will help you become a professional.

When I first put pen to paper, fingers to typewriter, I made all the mistakes editors groan about. My stories were dotted with characters with cutesy names, like Sammy Skunk. I wrote about putting a child to bed from the mothers point of view. I inserted dull directions to the illustrator, saying the character should be walking out the door or skipping down the walk. My characters were perfect children who never misbehaved; my plots were contrived, with an adult conveniently turning up to solve the problem; and my language was duller than an engineering textbook.

Navely, I thought my stories were so fabulous that an editor would make an offer of publication as soon as she read one. When, months later, my stories were returned with form rejections, I convinced myself that the editors didnt know what they were missing. After many form rejections (Im a slow learner), it dawned on me: I had serious learning to do. I signed up for classes, joined several writing groups, attended conferences, and read every book I could find about writing.

The importance of revision (that process between first draft and final submission to an editor) gradually seeped into my brain. I wrote this book to help you and other writers understand this faster than I did.

Writers can have three different kinds of reactions to their first drafts. Which one will be yours?

- Do you love your draft? Are you so enamored with your text you cant bear to change a thing? I thought my story about Sammy Skunk saving his friends Billy Beaver, Suzy Squirrel, etc. from Coyote Carl by spraying his horrible smell (big surprise there!) was imaginative, original, and perfect. I sent it out immediately.

- Or do you instead decide your story is hopeless and toss it in the trash? Ive done that, too. Once I wrote about a young Italian boy pulling up potatoes. Besides the fact that I had never lived in Italy or grown potatoes, the story felt thin. Convinced my writing was terrible, I tore it up and moved on, not thinking that I could at least plant potatoes and learn more about the process. Maybe if I was fortunate, I could even travel to Italy.

- The third reaction, which we should all strive for, is a combination of the first two. Thats where a writer reads her first draft and decides this isnt bad. She knows it isnt good either, so shes ready to play around and make it better. But what should she delete? What should she save?

Thats the problem. Its hard to be objective about what works and what doesnt in our stories. The key to improving your writing is to learn how to be your own critic, develop ways to pull yourself back from your story, and become an outside reader. How do you do that?

Many writers set a manuscript aside for days, weeks, or months to break through the love-or-hate affair with ones writing. This can help, but few have the self-control to hide a story in a drawer or under a bed for the weeks, months, or years necessary to acquire that objectivity. And theres no guarantee youll have much of that objectivity even after all that time.

Some writers know what they should look for in a revisionsuch as a strong opening, good plotting, three-dimensional characters, etc., but this is useless unless you know the characteristics of a strong opening, et al. We strive to create well-rounded characters, but few of us can recognize if our characters are flat or behaving inconsistently.

Some writers dont even try to become their own critics. They send their manuscripts to friends or family members or take them to writing groups. Outside readers who understand the craft of writing for children can be helpful. But the process of taking ones story to outsiders can be time-consuming, especially as you repeatedly edit your story and bring it back for further commentary. After too much of this back and forth, outside readers who never liked the story can become less helpful, while others may be so attached to itand to youthey lose their objectivity.