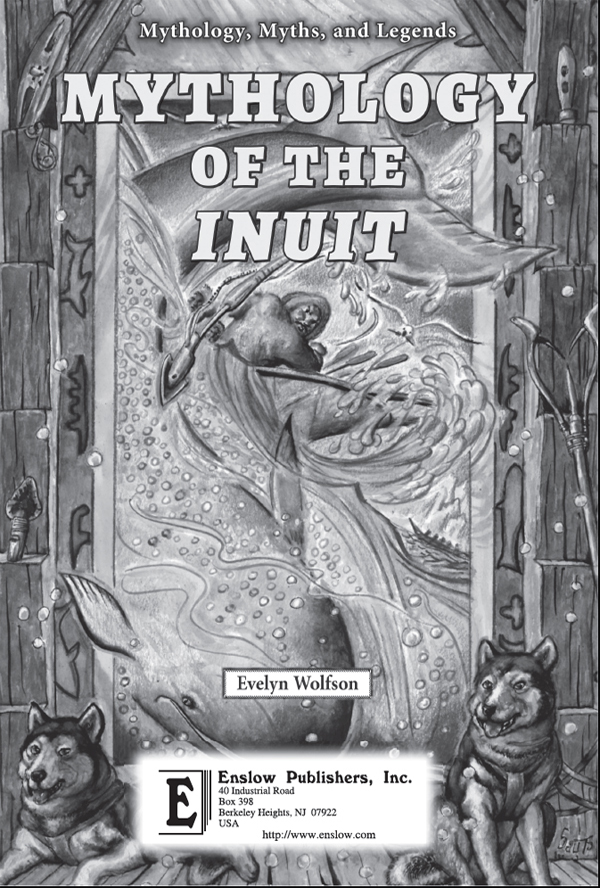

Unique Traditions and Myths

The long nights of the Arctic winter were a time for storytelling and for passing on the Inuit's unique traditions and myths. Storytellers told two kinds of stories: ancient and recent. Ancient stories told of fantastic thingsabout encounters with animals in human form, and about witches and sea goddesses. Recent tales included the adventures of hunters on land and seastories about courage, strength, vanity, and conceit. Each myth is enhanced by the expert commentary of noted scholars and mythology specialists.

The raw emotion and events of Wolfson's tales will appeal...

School Library Journal

Highly recommended.

Book Buzz

About the Author

For many years, Evelyn Wolfson had been a teaching specialist in Native American culture. Her books have won many literary awards, including those for Native American Children's Literature and American Indian Reference Books.

About the Illustrator

William Sauts Bock has illustrated many books, and his illustrations was honored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

The homeland of the Inuit (IN-oo-aht) people is a broad region of frozen land and sea that stretches from Alaska in the west to Greenland in the east. It is a land where trees are unable to grow, and only the hardiest animals and people can survive. Today, people of the North American Arctic are called Inuit, a term that has replaced the word Eskimo. Few of todays modern Inuit live where their parents or grandparents were born. Instead, they live in small cities and towns, mostly in southern regions of the Arctic. Traditional houses have been replaced by imported wooden ones, dogsleds have been replaced by snowmobiles, oil lamps have been replaced by electric lights and central heat, most foodstuffs must be imported, and television is the most important source of entertainment.

The Arctic covers the northernmost part of the earth and includes three continents: North America, Asia, and Europe. Less than one third of the Arctic is land. The rest is covered by the Arctic Ocean. The Inuit have lived in the North American Arctic for thousands of years. Descended from an early Siberian people, the Inuit arrived later to the New World than Native Americans. After they crossed the Bering Strait, they settled in Arctic North America and developed their own unique culture. Earlier and different groups of emigrants who came from Siberia and China beginning twenty-five to thirty thousand years ago migrated into the interior of North America and southward along the coast to South America.

Due to the tilt of the earths axis above the Arctic Circle, the suns rays never shine directly down onto the earths surface, and only a few inches of snow melt each year, leaving a foundation of permafrost, or land that never melts. In the southern Arctic, winter takes up six months of the year; and spring, summer, and fall fill the remaining months. From November until January the sun remains below the horizon, cloaking the frozen land and sea of the Arctic in total darkness. Most regions of the Arctic experience extremely cold temperatures in winter, and in January temperatures often average between 30 degrees below zero to 15 degrees below zero (Fahrenheit). As one travels northward, winter takes up more and more of the year, until, in the most northerly regions of the Arctic, winter lasts nine long monthsfrom September until June.

Over a period of several thousand years, the Inuit spread westward across the frozen tundra, a treeless stretch of frozen land that began where the northern forest ended and extended to the Arctic Circle. The people traveled from Alaska to Greenland following the rhythm of the seasons, always in search of food. In winter and spring they hunted seals, whales, and walruses; in summer and fall they fished and hunted caribou; and all year round they sought polar bears and musk ox. The Inuit adapted well to the severely limited resources of the region and met all their everyday needs using only the animals they hunted, the rocks that lined the shores, a limited supply of plants, and a precious offering of driftwood that washed in from the sea.

At the time of European contact, in the 1500s, the Inuit people shared basic religious beliefs and exploited the same natural resources. Life was a constant struggle for survival, and the threat of starvation was ever-present. The idea of a God, or a group of gods, to be worshiped was altogether alien to the Inuit. The Inuit believed that it was the powerful forces of nature that affected their lives. It was these forces that focused on balancing mankinds needs with those of the rest of the world.

In Greenland and Canada, the Inuit had no real creation myth. In Alaska, Raven was creator. Raven stories from Alaska resemble Native American Raven stories from the Northwest Coast. In Canada and Greenland there were a few simple myths about how the world was created but no myths that resembled the Raven tales. A Netsilik woman from Canada expressed her view of creation to Knud Rasmussen, the Danish explorer, in one sentence: The earth was as it is at the time when our people began to remember.

Unlike American Indians, the Inuit of Greenland and Canada did not have a mythological time period that took place before the appearance of humans during which animals behaved like people; thus mythological stories were scarce. However, one myth, the story about Sedna, the mother of all sea animals, was so widely distributed and had so many versions throughout Canada and Greenland that it made up for the otherwise lacking store of mythological tales.

Another lesser Greenland/Canada story was told about the origin of the sun and moon. It was about two siblings who argued and then chased each other out of their house carrying torches. The girl carried a brightly lit torch, but the brothers torch was dimly lit. The sister and brother rose up into the sky, and she became sun and he moon.

Unlike the mythologies of American Indians, in stories throughout the Arctic there was little mention of a transformer, or a character empowered to change peoples forms. And the only trickster, or culture hero, was Raven in Alaska.

The Inuit believed that all living beings had a soul that defined their strength and character as well as their appearance. After people died, their souls went up to join the stars and then became spirits. After animals died, their spirits went to live in a new generation of their species.

The Inuit observed important rules in their daily life to insure the well-being of the spirits. Many taboos, or bans, were associated with hunting and with caring for the bodies of dead animals. The Inuit conducted ceremonies and rituals to honor the spirits and observed important taboos to insure their good will. Taboos prohibited people from behaving in a way that would bring bad luck. For example, animal meat that had been taken on land could not be eaten or stored with meat that had been taken from the sea. Women could not sew new cloth or repair old garments after the spring sealing season ended. Instead, they would have to wait until the end of the caribou season in fall. In addition, certain rituals had to be carried out prior to butchering an animal. Before a seal could be butchered, for instance, its carcass was brought indoors and a lump of snow was dipped in water and dripped into the seals mouth to quench the thirst of its soul.

The Inuit world was filled with powerful spirits capable of vengeful and hostile acts toward people. But ordinary people could speak to the spirits and ask for help by using magical words. Magical words were kept very private and would lose their power if spoken in the presence of another person. People would also wear a magical charm, or amulet, in the form of a piece of fur sewn to clothing, or an animal tooth, claw, or bone worn as a necklace or on a belt. Amulets held spirit power and gave the wearer the character and strength of the animal whose object he or she was wearing.