Supernatural Characters

Long before they were written down, American Indian myths were kept alive by a strong oral tradition. These fascinating stories embrace a wide variety of supernatural characters. This includes animals, spirit-beings, and heavenly bodies. All of whom, many American Indians believed, helped shape the universe.

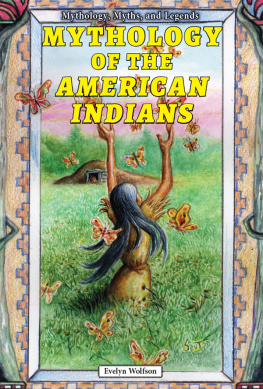

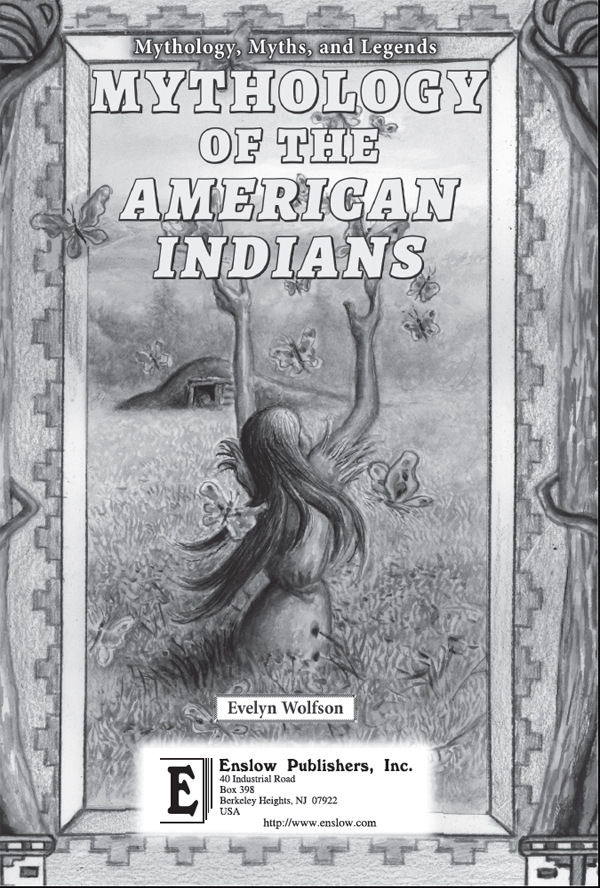

In Mythology of the American Indians, author Evelyn Wolfson weaves together traditional tales from nine different culture areas, showing the distinctions, as well as the similarities, among tribal lifestyles and legacies. Noted scholars of mythology and American Indian lore enhance each of the stories with their expert commentary.

...a compelling and straightforward narrative voice.

Childrens Literature

...gives a new insight into the cultures of these tribes.

Heart of Texas Reviews

About the Author

For many years, Evelyn Wolfson had been a teaching specialist in Native American culture. Her books have won many literary awards, including those for Native American Childrens Literature and American Indian Reference Books.

About the Illustrator

William Sauts Bock has illustrated many books, and his illustrations was honored by the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

American Indian myths and legends often include a variety of characters with supernatural powers, including animals and heavenly bodies, who help to shape the universe. Unlike the myths of Europe, Africa, and Asia, where the point of a story is often made to express a moral, these stories seldom moralize. However, they do tell stories that humanize the past.

In their early days, the Indians did not have a written language. Therefore, all of their myths were recorded by American ethnologists and anthropologists who relied on English-speaking Indian interpreters to translate for them. Most of these original translations contain only a skeleton of a storyonly as much information as the storyteller was interested in conveying.

Eventually, many Indians learned to write in their own language and recorded stories in both their language and English. Still, there has never been a systematic method of collecting and/or recording American Indian myths in any of the Indian languages, and many of the stories remain scattered throughout the journals of American anthropologists. Most of the tales I include in this book are taken from these early sources.

In my retelling, I have tried, as the Lenape say, to do so with a thinking heart. I stay as close to the original translations as possible, and I try to retain the spirit of the original, as if the old-time storytellers were speaking through meeven though I know the eye is less tolerant to words on a page than the ear is to a human voice.

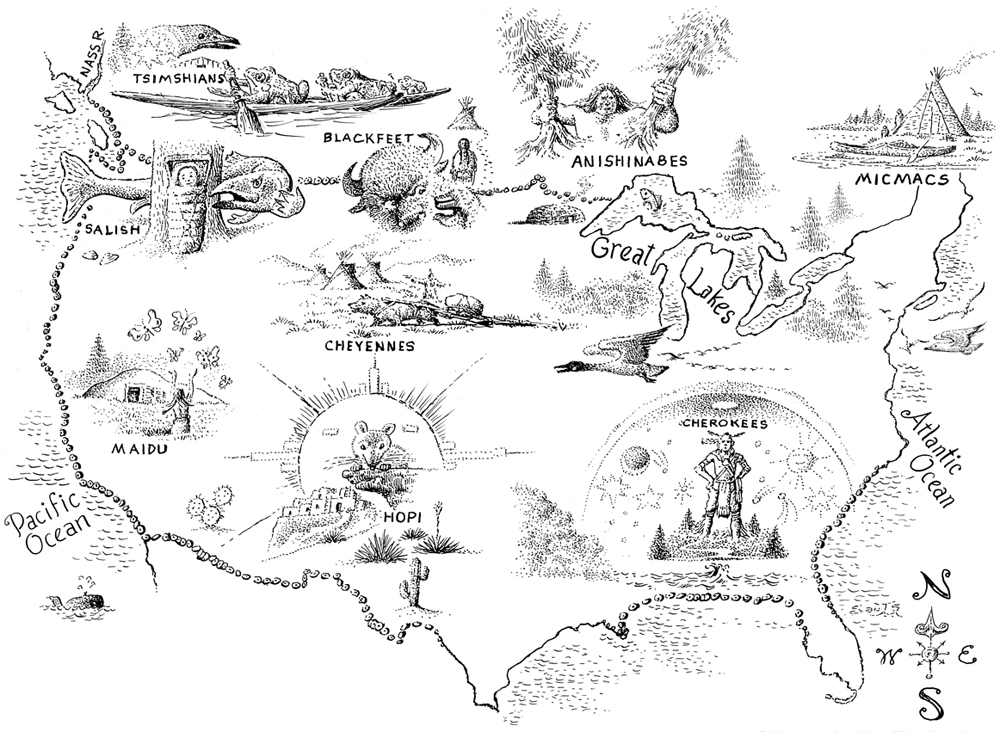

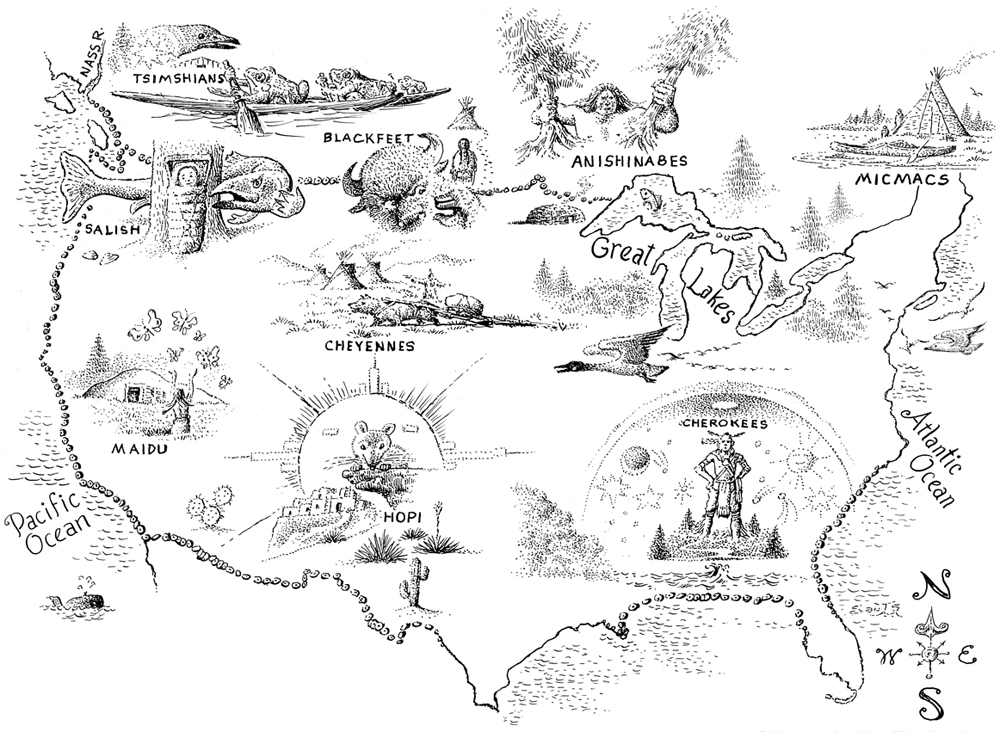

Traditional American Indian tales rarely had a beginning, middle, or end. Storytellers could begin their story wherever they chose because the tales were already so forcefully imprinted in the hearts and minds of the people. These stories were so real for them that a Blackfeet audience could feel the thunder of buffalo hoofs when they heard the story of how the buffalo gave themselves to the people. Likewise, Coast Salish tribes could hear the splash of the great migrating salmon when they listened to how Young Moon brought salmon to their rivers. People listened over and over again to their traditional stories, savoring the unique style and wit of each new storyteller.

Storytellers were always free to express their own individual interpretations of courage, cunning, and cowardice, as well as of pity and love. Thus, there are many versions of the same tale, even within a single culture area where people share a similar lifestyle. Rather than try to combine several versions of a story from one area, I have stayed faithful to a single version. For example, among tribes of the Pacific Northwest, who lived along the coast from northern California to southern Alaska, there are many versions of how Raven stole daylight. Only the Tsimshians version is told here to avoid homogenizing the culture of the region. The original homeland of the Tsimshians now lies in northern British Columbia (Canada) and southern Alaska.

A culture area is a geographical region occupied by people whose cultures are similar. For example, the lifestyles of the Tsimshians and Tlingits of the Northwest Coast are similar, but they are significantly different from the lives of the Blackfeet and Cheyennes who lived on the Great Plains, a vast region extending from central Texas in the south, to southern Canada in the north, and from the Mississippi River valley in the east, to the Rocky Mountains in the west. Stories from nine different culture areas are included in this book to show these cultural differences.

Mythological tales about how animals helped to shape the universe, particularly trickster tales, often reveal how people lived and what was important in their lives. In How Raven Steals Daylight from the Sky, for example, we learn that the Tsimshian people lived in dark cedar-plank houses, depended on salmon for food, and credited the trickster Raven for bringing daylight. In The Moon Epic, we learn that the Coast Salish people also depended on salmon for food, but they credited the heavenly body Young Moon for putting salmon in the rivers to keep their people well fed.

Other tales are simple stories, and the plot is the story. Tolowim-Woman might be a cautionary tale, or a metaphor for death. It is the story of a woman who falls in love with and follows a beautiful butterfly. In the end, the chase kills her.

Native-American origin myths are unique in that they tell about how the world was created in a single tale. In the Cherokees myth, How the World Was Made, Beetle pulls mud up from under the water to create a suitable habitat for the Cherokee people, and Grandfather Buzzard flaps his wings to form the landscape.

I also include stories that explain the origin of special ceremonies. Among the Blackfeet people of the northern plains, the story about Buffalo Husband explains the origin of the annual buffalo dance. Hopi people of the desert southwest have a story, The Kachinas Are Coming, about several of their kachinas, or spirit-beings, who grant wishes to young boys when they are hunting. These, and other kachinas, act as mediators between the living and the dead. They appear each year during the winter solstice celebrations wearing costumes and masks, and they dance to bring rain and prosperity.

Some American Indian tales tell about natural occurrences, or about the changing seasons. The Cheyennes story, Winter-Mans Fury, describes how Bow-in-Hand used his magic eagle-feather fan to drive heavy snow from the southern plains.

Another story, Mandamin, is a fertility tale that tells about the care and nurturing of corn, which symbolizes the continuity of life.

In the story Glooscap the Teacher, Glooscap is shown to be a hero who teaches the Micmac people all they need to know in order to succeed on earth, as well as how to reach the world beyond. His trickster side is also revealed in this myth.

American Indian oral traditions have kept these tales and many others like them alive for generations. I am grateful to the many devoted scholars, both Native-American and non-Indian, who have recorded the stories for all of us to share.