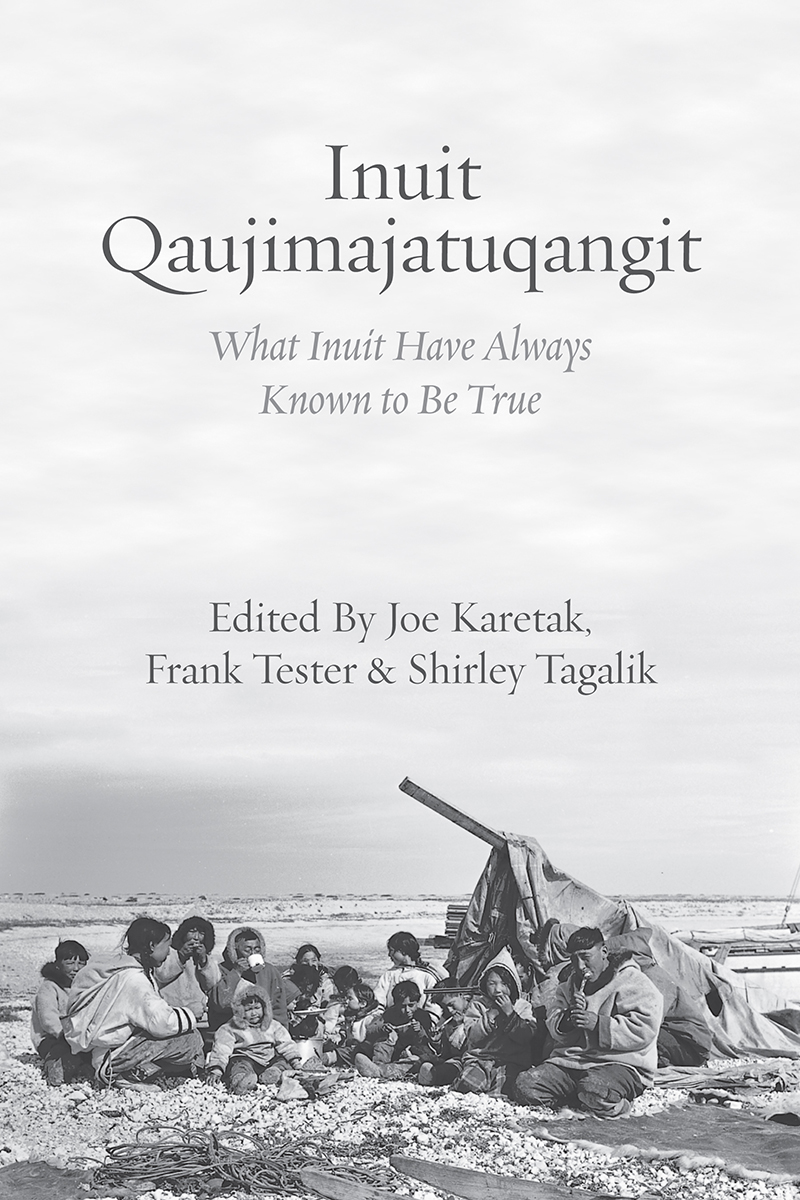

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

What Inuit Have Always Known to Be True

Edited by Joe Karetak, Frank Tester & Shirley Tagalik

Fernwood Publishing

Halifax & Winnipeg

Copyright 2017 Joe Karetak, Frank Tester, Shirley Tagalik

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Editing and text design: Brenda Conroy

Cover photo: Family picnic on the beach

Cover design: John van der Woude

Printed and bound in Canada

eBook: tikaebooks.com

Published by Fernwood Publishing

32 Oceanvista Lane, Black Point, Nova Scotia, B0J 1B0

and 748 Broadway Avenue, Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3G 0X3

www.fernwoodpublishing.ca

Fernwood Publishing Company Limited gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage and Tourism under the Manitoba Publishers Marketing Assistance Program and the Province of Manitoba, through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, for our publishing program. We are pleased to work in partnership with the Province of Nova Scotia to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Inuit qaujimajatuqangit : what Inuit have always known to be true / edited by Joe Karetak, Frank Tester & Shirley Tagalik.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55266-991-4 (softcover).ISBN 978-1-55266-992-1 (EPUB).

ISBN 978-1-55266-993-8 (Kindle)

1. EthnoscienceCanada. 2. InuitCanada. 3. InuitScienceCanada. 4. InuitCanadaSocial life and customs. I. Karetak, Joe, editor II. Tester, Frank J., editor III. Tagalik, Shirley, editor

E99.E7I5854 2017 001.0899712

C2017-905049-4 C2017-905050-8

Contents

Acknowledgements

We thank our funders, the Arctic Inspiration Prize, made possible by Sima Sharif and Arnold Witzig, and the Arctic Inspiration Prize Selection Committee for recognizing the importance of this project. This funding provided the opportunity for the Elders to conceptualize this book. We also thank the Nunavut Ministry of Culture and Heritage for its funding and ongoing support for Elders and cultural enhancement, and the National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health for their support and direction. Research grants from the Social Sciences Research Council ( SSHRC ) supported Franks work and helped make his participation in this project possible.

All photographs are from the Gleason Ledyard Collection, courtesy of Mark Kalluak, unless otherwise indicated. We are grateful to everyone who shared photographs for this book. There are thousands of photos of Inuit in archival collections. Most of them, regrettably, are unnamed, as is true of Inuit shown in photos used in this book.

We are indebted to Frank Tester for his participation, advice and contribution to the book. We are also very grateful to our team of exceptional translators: Nellie Kusugak, Saimanaaq Netser, Rebecca Mike and Suzie Napayok.

Above all, we thank our Elders. Some of those who contributed to this volume are no longer with us. We recognize their devotion to promoting and revitalizing Inuit culture in order to provide well for future generations. Their rich experience, time, energy and commitment to Inuit youth and future generations, and hopefully to all who take seriously the urgent need for us each to find a different way of appreciating and relating to others and the world around us, is what has made this book possible.

Foreword

Creating the Book

Shirley Tagalik

This book is the result of a project undertaken with and by Elders from across Nunavut Territory. It has been an honour to do research with these Elders. We began this work in 2000, not knowing where this exploration of Inuit knowledge and worldviews would take us. It was a journey taken by Elders, where we facilitated and followed their lead. Participating has been for all of us a privilege.

The process began tentatively. Elders were not sure we could be trusted with their insights, experience and wisdom. They were concerned about how these might be used. Inuit culture is an oral one, and the prospect of writing a book was daunting. They were also hesitant because they were being asked to reach into a deep reservoir of experience and feelings blocked off at the time of forced relocation and colonization. Frank Testers chapter describes the traumatic experiences that were a reality for Elders contributing to this book. For Elders from some regions, this information had been blocked for more than a generation. The process had to allow time for collective healing, building a trust relationship and reconnecting with the past and cultural teachings that were suppressed in this colonial period.

Rhoda Karetak expressed this eloquently when she shared a dream she had with the group.

I had a dream. I was carrying a baby that was not well. I knew that it was not my baby, but, because the baby was so sick, I started thinking that I wanted to just bury the baby. As I thought this, I could hear a very faint voice saying, You cannot do that!

Yes, I know I cant. I knew there is a law that prohibits doing something like that and that I might end up facing charges. I fully agree with that law. But then I got a stronger thought an overwhelming urge to bury this baby. I was thinking, I can do this. I have the authority to do this thing.

In my dream, I started to dig a spot to bury the baby in a small crevasse in the ground. I was all by myself, so I took the sick baby and buried it. The face was not buried because the baby was still alive.

I started leaving and, as I was walking away, there was a very loud noise. The crying continually became louder. It became so loud that all nature heard it. At that point, I knew I had to go back.

When I picked up the baby that I had buried, it stopped crying as soon as I picked it up. I realized that it was the most beautiful baby. The baby was well and happy as soon as I picked it up. I was happy too.

Now why would I dream such a dream? I started to reflect on this because I knew that this was not just an ordinary dream. Then I suddenly recalled something Inuit culture was once absolutely alive but has been getting buried. It was like when you bury a dead person, but this was something that was really still alive and active even though it was being buried. I knew that my dream was about the need to revive Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit .

Through her dream, Rhoda put into expression the feelings of many Elders. This confirmed that they needed to commit to the work of reviving what still remained of the deep knowledge that is Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit ( IQ ). The process of documentation began.

In one of the group meetings that preceded our focus on the book, and while he was working with the Department of Education, Mark Kalluak noted the following:

Some might think that Inuit never plan for the future. They sometimes think that we lived from day to day with no plan. We are here today because our ancestors were the ones who made sure that we could survive. They did not live one day at a time. We were made to become human beings right from birth. They taught us how to live a good life and what to do in difficult situations.