Contents

Sir Ernest Shackleton

SOUTH

The Endurance Expedition

Introduction by Fergus Fleming

Photographs by Frank Hurley

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

South

Sir Ernest Shackleton (18741922) wasprobably the greatest of all the Antarctic explorers. He was born in County Kildare,joined the Merchant Navy and was a junior officer in Captain Scotts 19014expedition. He led the British Antarctic Expedition (190709), the ImperialTrans-Antarctic Expedition (191417) and died on the Shackleton-Rowett Expedition(192021). South is his record of the second of his expeditions, whichculminated in Shackletons extraordinary rescue of his men through successfullynavigating a 20ft lifeboat 720 nautical miles from the edge of the Antarctic to SouthGeorgia.

Fergus Fleming is the author of KillingDragons: The Conquest of the Alps, Ninety Degrees North: The Quest for the NorthPole and Barrows Boys.

Introduction

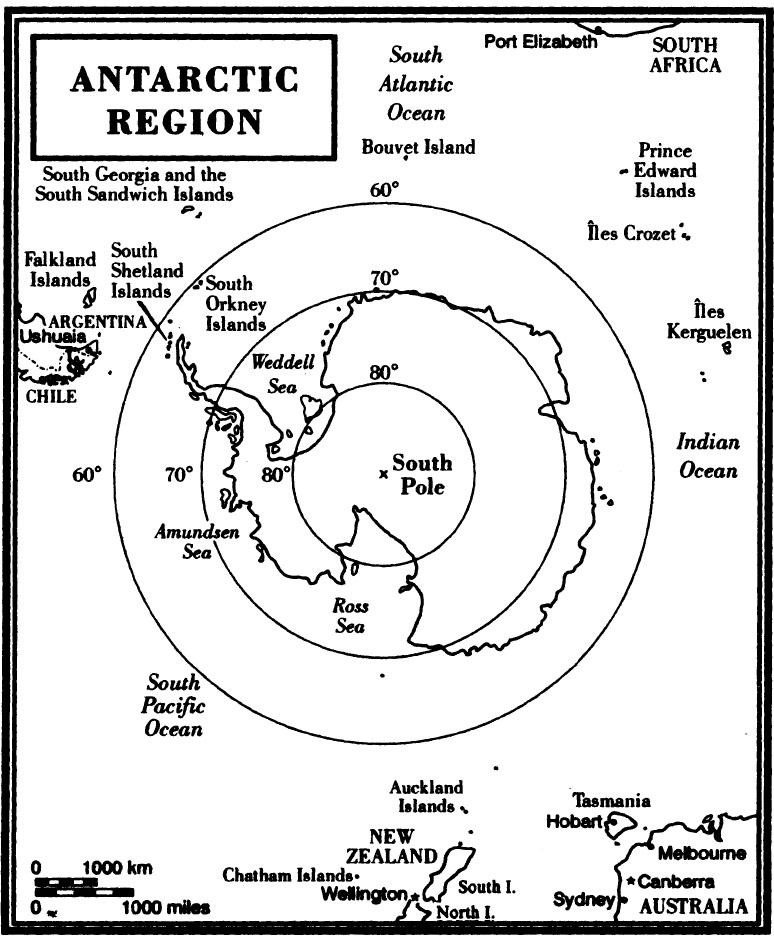

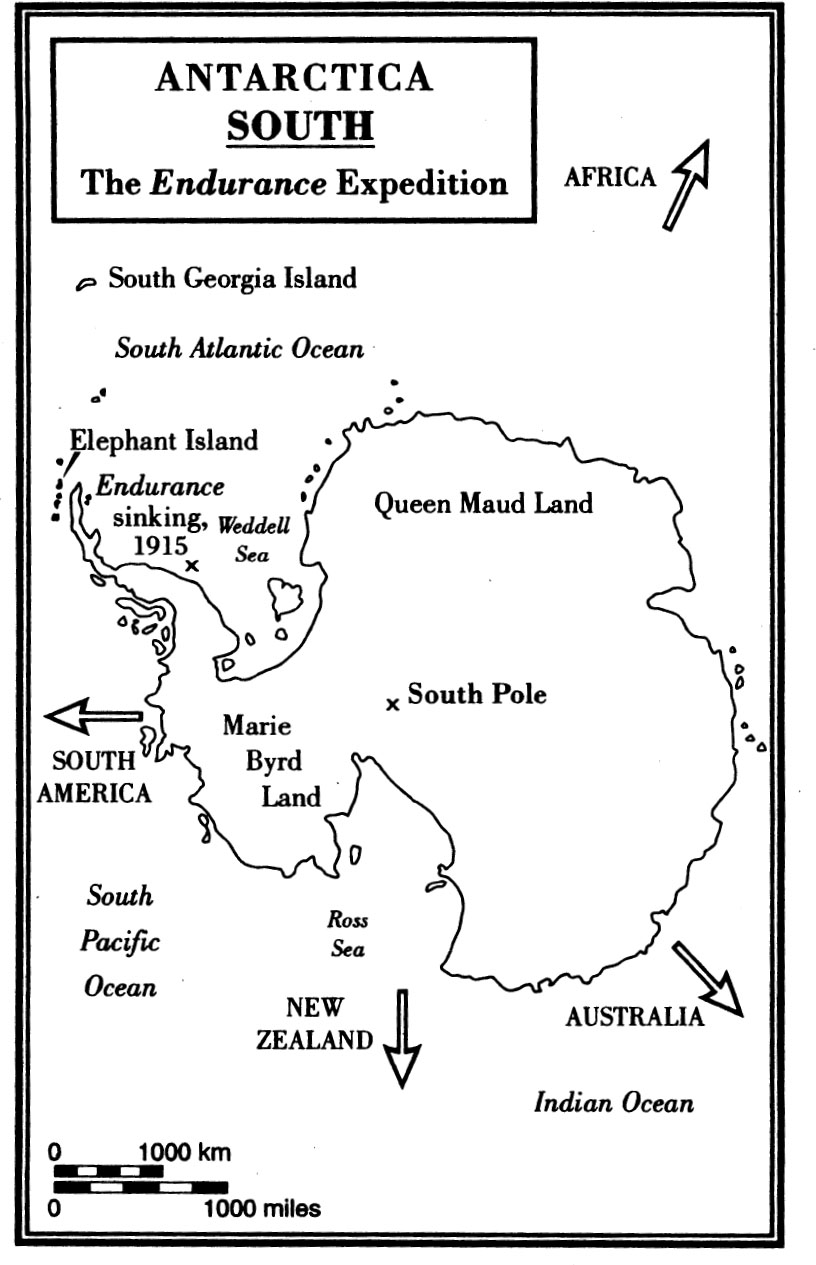

On 8 August 1914 Ernest Shackleton leftPlymouth aboard the polar research vessel Endurance, bound for the South Pole.For many years he had coveted the earths southern axisin 1908 he hadsledged to within 100 miles of the spot, discovering en route the South MagneticPolebut it was no longer a goal that could be sought in its own right. RoaldAmundsen and Robert Falcon Scott had already captured it in 191112. Shackleton,however, sought to outstrip his forestallers (a word much favored by the polarfraternity) with a feat of breathtaking audacity. As leader of the Imperial TransAntarctic Expedition he planned not only to reach the Pole but to cross from one side ofAntarctica to the other. He and his transcontinental party were to battle through theice-choked Weddell Sea aboard the Endurance, while a support ship, theAurora, would attack via the Ross Sea. When both teams had landed theywould dissect the continent with ferocity, Shackleton and his men advancing from oneside while the Aurora team laid anticipatory food depots on the other.Meanwhile, scientists from both ships were to fan out and investigate their immediateenvirons. If all went well, Shackleton hoped to come home in 1915 with the mostcomprehensive scientific and topographical analysis of Antarctica to date, a sensationalattainment of the Pole, and the news that the Union Jack flapped resolutely at thebottom of the world.

In the Endurance, hewrote, I had centered ambitions, hopes, and desires. How, then, he musthave been disappointed when his ship foundered in the Weddell Sea, forcing him toabandon his odyssey and subsequently to make one of the most harrowing escapes in the history of exploration. How, too, he must have been demoralized when,on his return, he had to relive the experience. From December 1919 to May 1920, at thePhilharmonic Hall in Great Portland Street, he lectured twice daily on his calamitousforay; and as he spoke, Frank Hurleys film of the expedition flickered silentlyon the screen behind him. Possibly it was the most memorable show-and-tell in history.Shackleton, however, found it uncomfortable. Twice a day, he had to revisit thedisastrous culmination of his ambitions and desires; and not only revisit it but explainit, set it in context, delve into each unpalatable detail of a voyage that, despite itsheroic outcome, had been an expensive and disappointing failure. It might have beeneasier if those to whom he lectured were present to deliver some form of judgment, toappreciate his humiliation, or, at best, to show a degree of interest greater than thatof mere attendance. But he did not even have that consolation. Most of the time thePhilharmonic Hall was only half-filled. People were devastatingly unconcerned.

Shackleton belonged to the Age of Heroes, aperiod stretching from 1888 to 1914, in which individuals, financed privately orotherwise, assumed the burden of polar exploration that had previously been borne bygovernment. The appellation is apt for it was indeed an age when heroism ran amok. Menpursued, in the words of more than one explorer, something big, the sizeof the exploit being seen as a measure of ones spiritual and physical worth in anincreasingly humdrum industrial world. The poles were big and explorerstherefore went after them. The roll call included Nansen, Abruzzi, Andre, andPeary in the Arctic; Scott, Amundsen, Mawson, and Shackleton in the south. Theirtravails, and on occasion their deaths, were followed with avidity by a sensation-hungrypublic. But the concept of heroism evaporated in the trenches of the First World War.When Shackleton sailed for the Antarctic in 1914, he could still be a hero. When hereturned in 1917 he could not. The war had produced a surfeit of suffering against whichhis antics were of piffling importance. When, for example, the Aurora cabledfor assistance in 1916, Winston Churchills responsewasunderstandablynegative. When all the sick and wounded have been tended, he wrote, when all their impoverished 7broken hearted homes have been restored, when every hospital is gorged with money, 7every charitable subscription is closed, then 7 not till then wd. I concern myself withthese penguins. I suppose however something will have to be done. In post-warBritain nobody wanted to hear about heroism. When Shackleton mounted the podium at thehalf-empty Philharmonic Hall, he must have been aware that he was a man from thepast.

These were the circumstances in whichSouth was written, and, to some extent, they inform its content. From itsdedicationTo MY COMRADES who fell in the white warfare ofthe south and on the red fields of France and Flandersto its explanationsas to why the expedition sailed south instead of joining the war, and how its membersfared on their return (three were killed in action and five were wounded), one can senseShackletons discomfort at being placed so immediately in historical context. Whatwas his story worth against those of Passchendaele and the Somme? The marvel ofSouth, however, is that it is not written as a story. It is, instead, anexplorers journal that describes conditions as accurately as possible for thebenefit of those to come. When writing about the Weddell Sea ice trap, the movement ofice, the flow of currents, the direction of winds, and the availability of food,Shackleton seeks not to entertain but to inform. When describing the mechanics of hisstove, the lack of water, the blizzards and the shiny emptiness of the pack, he does sobaldly. He annotates the moves from Dump Camp to Ocean Camp to Patience Camp in plainterms. His voyage to South Georgia aboard the James Caird is related withrestraintdespite surviving a wave so massive that at first sight he mistook itscrest for clear sky on the horizon. Only on his final trek across South Georgia withCrean and Worsley, over mountains that had never been climbed before, does he titillate.Who was the famous fourth man who paced in the shadow of their consciousness? Was he afigment of their exhaustion or was he, as all three felt, Christ? The image was sostrong that it found its way into T. S. Eliots